Before we get into the detail on what a process to create a communications strategy looks like, it may be worth considering why to go down that path in the first place.

What is strategy?

At Cast from Clay, we think of strategy as the prioritised deployment of limited resources against agreed objectives. If you have unlimited resources, it matters not how you use them. Do everything all the time. Most of us are not in that position. We must be selective in how we expend our resources (staff, budget, reputation, etc.), in what order, and to what end. Coming up with a commonly accepted roadmap, a strategy, keeps us focused on what is important.

Strategy is useful because it allows us to say “no”. All too often we are met with requests to invest in new software, hire that cool communications agency 😎, or chase research funding that isn’t aligned with our mission. Without a clear set of objectives in place, and detail on how to achieve them, we lack conformity and alignment of approach.

A clear strategic vision permits ruthless clarity of thought and focus. It helps us say “no” to things that will distract us. This in turn allows us to efficiently allocate resources, which increases the likelihood of impact. So, as someone much wiser than me once said, strategy is making sure you do the right thing. Whereas execution is doing things right.

Different kinds of strategy

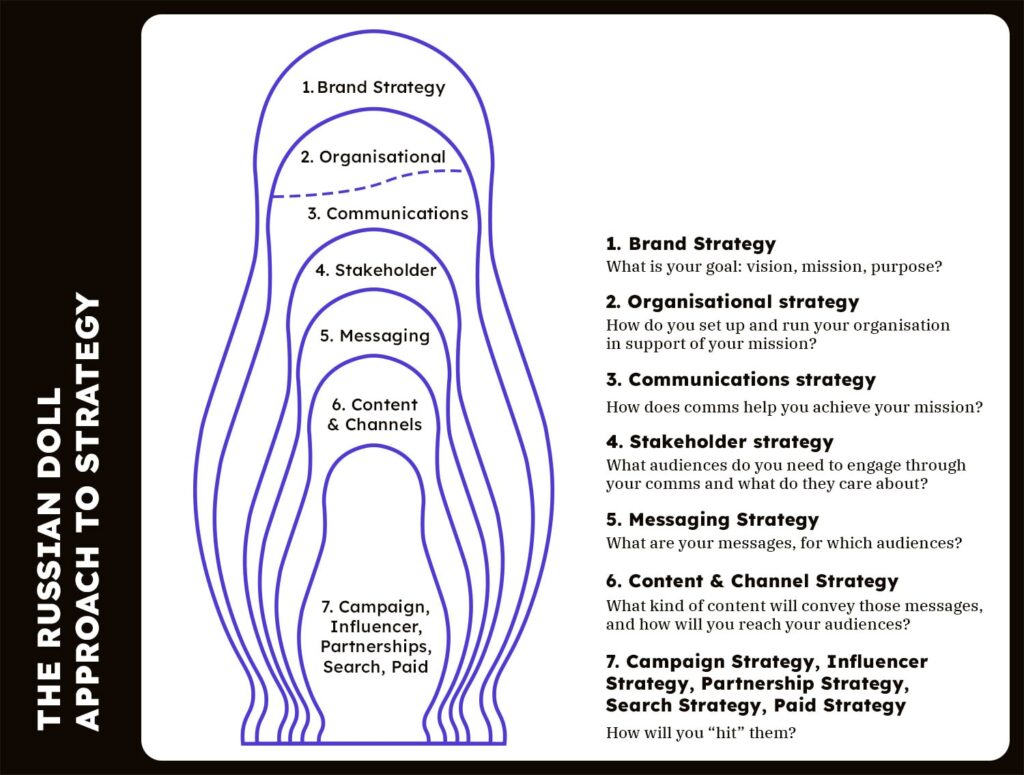

There are lots of different kinds of strategy. Think of a Russian doll. The outer doll is your brand strategy. It’s the big stuff: mission, vision, purpose, values. Without this, you are directionless. The doll just inside is your organisational strategy. Our context is communications, so for us this is our communications strategy. But it could also be your HR strategy, your IT strategy, your financial strategy. All the different strands that help you achieve your brand strategy.

And within this communications strategy doll you have a number of others (we’ll talk more about these shortly).

What is a communications strategy

The driving question behind an organisational communications strategy is broadly “How does communications help my organisation achieve its mission?” To do that, you need answers to the following questions:

- Objectives and goals. What is my overarching communications objective(s), and what are the goals that sit underneath this?

- Audiences. Which audiences are important to achieving each goal, both in terms of the primary audiences who make the decisions I need to influence, and the secondary audiences who shape the opinions of my primary audiences? (n.b. ‘policymaker’ is not a good audience definition)

- Desired change. What exactly do I want my audiences to do or think (or be aware of)?

- Audience insight. Where do my audiences stand on the matter at hand, what else do they care about (that’s relevant), and what are the barriers to them doing what I want?

- Messages. Which messages are most likely to have the effect I seek?

- Messenger. Which messenger is best placed to communicate the message?

- Channels. What channels should I deploy those messages through (social media, drinks at a cocktail bar, a conference event etc.)?

- Measurement and evaluation. How will I know whether my communications has been successful, and how will I measure it? (you may enjoy this piece if you’re thinking deeply about policy impact)

The thing to watch out for when you create a communications strategy

Yes you want to answer all the above questions, but it doesn’t matter how good your strategy is if no-one uses it or respects it. If your goal is to create a situation where you can say “no” and keep people aligned, you need to know what you’re going to do, but you also need to ensure that your strategy is subscribed to by colleagues and stakeholders. You will need to have created an environment in which you can say “no”.

Consider speaking to senior leaders across your organisation and engage them formally or informally in the process from the outset. Questions that may be helpful to ask:

- What do you think of the current communications strategy and/or approach? Does it work or not for you? Why?

- What does the current strategy do well?

- What would you like to get from the communications strategy/team that you’re not currently getting?

- What are we currently doing on communications that you think we should stop?

- Who do you look at and think “they know what they are doing on comms”? Why?

- Say we revise the communications strategy now, and in 5 years time you look back and you think “that was an epic strategy”. What had we done? What did we achieve to make you say that?

- Which audiences matter to you and what do you want from them?

- Should the strategy be light touch to allow different parts of the organisation to use it in their own way, or highly detailed so that the approach is more uniform across the organisation?

How to develop a communications strategy

You know the information you need to get, you know what you’re trying to achieve, what now? Here’s the nuts and bolts of the process we use.

1. Understanding the context

Our goal here is to generate a contextual understanding of the landscape you operate in. You should choose a handful of organisations, which include a couple of competitors and best-in-class organisations (from another policy area, perhaps), and a curve ball, maybe a media organisation or a consultancy or a consumer brand.

Rank them on 5-10 areas, from positioning to messaging to channels. What you rank them on should be dictated by the elements you intend to include within your strategy (and maybe driven by some of the internal conversations you’ve already had).

Focus on questions like: Why are they doing what they are doing? What can I learn from what they are doing? What are they doing that you should avoid repeating? What are the opportunities/ where is the white space? What new questions do I have after doing this?

Your deliverable should be something like 10-20 slides, with a 2-3 slide executive summary (not densely packed with words – you need to get to the point where you are really clear on what this output means for your organisation).

2. Conducting primary research

With primary research we want to understand how our key audiences think about your organisation. Conduct minimum 5 interviews with each audience type (eg, media, funders, policymakers, employees, senior management/ board).

Questions should be both absolute (ie, what do they think of you) and relative (ie, what do they think of you compared to your competitors). You may want to test the findings of the landscape research, or do some preliminary message testing. You’ll definitely want to identify conflicts between internal and external audiences.

Focus on: what do your audiences want from you? How do they frame the conversation? What is missing? What are the problems? What are their barriers? What are the opportunities/ where is the white space? What questions remain unanswered?

Again, clarity of thought in the deliverable is important. Don’t just repeat what everyone said, but identify what it means for you moving forward.

3. Securing internal buy-in

If the goal is to create an environment where you can say “no”, you need to earn that permission. So here we need to listen to the organisation, and give them the opportunity to feed into and shape the strategy. You’ll have already done this a bit, by speaking to senior leaders at the beginning, and then engaging a handful of board members and employees, here is where you want to engage a bit more widely — assuming these colleagues are important to making the strategy a reality.

How you do this will differ depending on the type of organisation you are, and your scale. A workshop (or several) is a good default as it allows you to get different parts of the organisation in the room together to discuss and debate areas where there may be disagreement.

Use the workshop to explore the findings from the preceding research phases so everyone is on the same page about the situation at hand, and then use the space to resolve internal and external conflicts. Test some of your initial ideas for the strategy – do people think they will work?

Most importantly, listen to the voices in the room. This isn’t a tick box exercise but a crucial component of developing a strategy that will work. If there are reservations about a specific component, it’s likely that it isn’t viable in its current form. Hammering it through won’t help anyone.

4. Developing the communications strategy

Find a cave, gather your notes, turn off your email, and start building the strategy out in detail. We tend to approach strategy by defining a set of pillars up front, and then fleshing them out. So for one previous client, these were:

- Frame the Debate

- Deepen Relationships

- Focus on Accessible Content

- Evaluate Constantly

Each pillar should have a strategic goal(s), recommendations on specific tactical executions to achieve them, and a snapshot of the research that informed the goal. You’ll want to include some things that you can do tomorrow, and others that will require increased investment – so realistic, but also pushing you forward.

Most importantly, you need to make the strategy real. Avoid creating a strategy that is so big picture that it lacks real meaning. Add the detail and the colour.

Questions that may help you here include:

- When should we do this and how long will it take?

- What resource is required to make this happen? Where will it be drawn from?

- Who has responsibility for making this happen?

- Do we need external support? If so, what kind of individual/ firm, and who do we know who may be a good fit?

Defining a measurement and evaluation framework isn’t always part of a communications strategy brief, but it is something you should be doing alongside this. What KPIs are you targeting and what are your metrics for success?

Improve your impact on our online course

Find out moreCommunications strategy examples

We’ve developed a number of communications strategies for for organisations, executives, and to govern policy campaigns. These have included:

- Consulting on the most effective way to frame a contested school-food policy proposal among British parliamentarians. {CASE STUDY}

- Devising and launching a campaign around the economic cost of food systems to provoke policymaker engagement across a range of influential markets – EU, China, India, Brazil etc. {CASE STUDY}

- Building a public constituency for humanitarian causes, engaging the private sector to raise the issue in the domestic political agenda for Save the Children UK. {CASE STUDY}

- Running a coalition-led campaign to drive investment into sustainable livestock production in Global South to help small and medium-size farmholders adapt to climate change. {CASE STUDY}

Chat to us about your strategy

Email TomFAQs: how to write a communications strategy

Why is it important to develop a communications strategy?

There are a number of reasons why developing a communications strategy is important. It helps you retain your focus on what is important (and ignore what is not). Through the process of developing one, you’ll better understand your audience needs and wants. It also can be a very useful tool to ensure that a wider team is bought into a specific communications vision and roadmap – by involving them in the creation of the strategy, and thereby (hopefully) ensuring they will work to bring it to life.

How to create an effective communications strategy for nonprofits?

Key to creating an effective communications strategy for nonprofits is understanding the specific role that an organisation plays, compared to others in its space. All too often nonprofits communicate as if they are the only actor in their policy space – this isn’t realistic, and it will impede their ability to have impact. Those that work at nonprofits often do so because they believe in the cause. This is important, but it can give way to a flawed assumption that everyone else believes in the cause too. This can prevent the development of an effective strategy, because the foundational audience insights are incorrect.

Who should be involved in developing and deploying a communication strategy?

It’s essential that the (internal and external) stakeholders that you wish to communicate with are researched as part of the development of a communications strategy. But don’t make the mistake of thinking that those stakeholders are decision makers on the strategy. Ensure you are aware of all the challenges, opportunities, and perspectives around whatever issue or organisation you are communicating on, but hold the decision making reigns tightly. A communications strategy that is designed by committee (or overly influenced by audience research) will in almost all circumstances be terrible.

What are the ethical considerations in developing a communications strategy?

Ethical considerations in developing a communications strategy include transparency, honesty, respect for privacy, and integrity. It’s essential to communicate truthfully and accurately, respect the rights and dignity of individuals, and adhere to ethical standards and regulations governing communication practices. Basically, don’t be an idiot.

What are the best practices for developing a communications strategy?

The three things that make a communications strategy better are a) very clearly defined objectives with associated metrics and KPIs b) detailed audience research (ideally qualitative and quantitative), and; c) a recognition that strategy is both art and science. Yes, ensure your work is informed by audience research and insight, but don’t be bound to what the audiences have said.

What goes wrong when developing a communications strategy?

We see these five things relatively often – and they tend to prevent an organisation from achieving impact:

- Lack of brand strategy: you can’t develop a communications strategy unless you know your brand. It will be bad.

- Lack of audience definition: ‘Minister of Education’ is a defined audience, ‘policymaker’ is not.

- Lack of trust between comms and policy teams: a strategy project won’t fix a cultural problem

- Trying to do too much: do a few things exceptionally well

- Budget realism: be realistic about what budget you have available to deliver on the strategy