This is an ongoing topic of conversation: What does storytelling look like for think tanks? How do you turn a report into a story? Here is our attempt to shed some light on the issue. It’s a 5-part blog – and we’ve approached it much like building a house:

The Think Tank Storytelling Series

1. Laying the foundations > Defining the terms | Part 1

2. Building the frame > Recognising values and assumptions | Part 2

3. Installing the walls > Research in the world of story and narrative | Part 3

4. Designing the interior > Mapping your story | Part 4

5. Picking the furniture > Features of storytelling | Part 5

This is our third blog in the series.

Research in the world of story and narrative

Think tankers’ currency – their bread and butter – is research. So we start by looking at the context in which research is published, before suggesting two levels of storytelling think tankers need to consider.

The myth of the objective, standalone report

To begin, a sober assessment of the context of policy research. In a nutshell, we need to be honest about the fact that research a) is informed by our organisation’s assumptions, and b) does not get released into a vacuum.

Research is informed by values and assumptions

First, research is informed by the values and assumptions of the organisation. For all that the methodology may be robust and impartial, these dictate at the very least what questions are explored, and their interpretation.

- Research by the US’s Heritage Foundation comes with the assumption that the role of the state should be minimal beyond securing national borders.

- Research by the UK’s Adam Smith Institute comes with the assumption that free markets are the most effective way to allocate resources.

- Research by the UK’s Institute for Public Policy Research comes with the assumption that the state should relieve poverty and support the less fortunate.

- Research by Brookings in the US or Chatham House in the UK comes with the assumption that multilateralism is the most effective way to mitigate international conflict.

The idea of “objective” research has been a useful narrative for many think tanks in the mainstream. But in a world where mainstream is becoming increasingly associated with urban liberal thinking, how convincing is this idea?

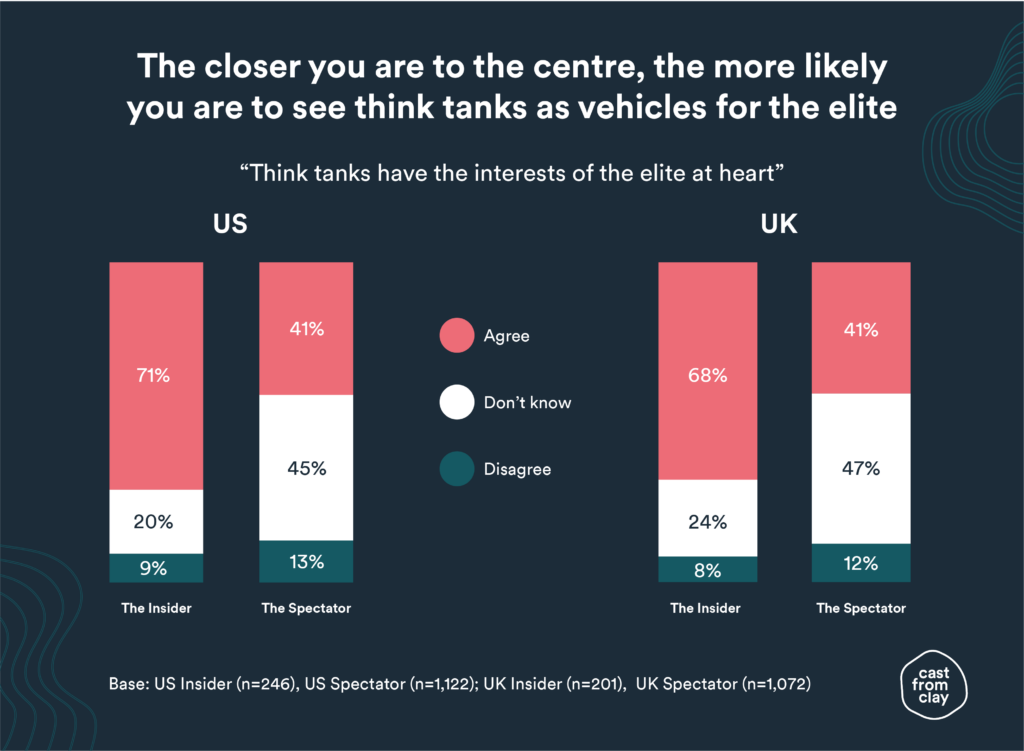

Our 2018 research in the US and the UK revealed that, overall, think tanks are seen as vehicles for the elite. Interestingly, this is true for both the general public who are interested in politics (‘Spectators’), and even more so for those who work in politics and policy (‘Insiders’). (You can find out more about our segmentation of public audiences here.)

If think tanks are indeed not perceived as the impartial arbiters they would like to be, it is essential for think tankers to tell the story of what they do stand for. Failure to do so will leave it up to their audiences to fill in the gaps.

This notion has been confirmed by a number of anecdotal conversations since, with both policymakers and journalists. The reaction is typically:

“Of course every think tank tank has an inherent bias. What organisation doesn’t? But that’s fine. We don’t use think tank research because of ‘objectivity’, what actually matters to us is the quality of their research and their track record. We’ll interpret their angle at our end.”

Research by think tanks who embrace talking about what they stand for – e.g. Heritage Foundation, Cato Institute, Adam Smith Institute, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (to an extent) – is no less routinely used by policymakers and media alike.

By virtue of being open about what they stand for – their values – these think tanks find themselves far better equipped to tell stories.

Research does not get released into a vacuum

Secondly, we are all familiar by now with the notion that our relationship with facts and data is a lot more complicated than it used to be.

What remains true is that facts and data will simply be ignored if they don’t fit with one’s pre-existing narrative. (We explored this extensively in our research last year.) This reality is a challenge for think tanks who are interested in having an impact on the policy debate.

Conversely, facts and data will be co-opted if they can act as proof-points to a pre-existing narrative. And perversely, those very same facts and data can be used as proof-points for a competing narrative.

Last year, for example, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) in the UK published a report on the top 1% of income tax payers. The research was picked up by both the Left and the Right – it reinforced both a left-wing narrative of unchecked inequality, while feeding a right-wing narrative of the top 1% as heroic wealth creators.

The point is: the environment within which research is released is not neutral – it has agency. Which is why framing matters. Framing is about taking control of the narrative, to the extent that it’s possible.

We would all like to think that the data comes first, it will speak for itself, and then the appropriate narrative will unfold. Unfortunately, the evidence shows that it’s the other way round. For policymakers just as for the general public.

If think tanks don’t engage in narrative-setting, they are forever relinquishing the framing of their research to their audiences – media, politicians, activists – who have their own agendas and little interest in the integrity of the evidence.

This is a reality that climate change researchers learnt a few years ago for example, and that migration researchers are starting to look into.

Two levels of storytelling for think tanks

Having considered the context within which research and reports are released, we are now in a position to think about a framework for storytelling. In thinking about storytelling for their organisation, think tankers must consider two levels:

- THE MESSAGE: Conveying the story that the data tells us in the most impactful way – through facts, but also through emotion.

- THE ENVIRONMENT: More long term, feeding into, influencing and shaping the narrative(s) around the topic at hand at a societal level.

The audience for the former is specialist – politicians, policymakers, think tankers and academics. The audience for the latter is broader – the informed public (‘Spectators’), which of course also includes policy specialists.

The message

Through data visualisation and interactive tools, we have made great progress over the last decade in how to bring data to life. While this can be effective, this paradigm remains one of fact-based communication. And we have witnessed its limitations in the past few years.

Storytelling is about telling a more rounded story than simple facts and stats allow. It is about bringing it back to the human. It is about introducing emotion – in support of facts, not at the expense of facts.

Facts and stories are not mutually exclusive – in fact, academic studies have shown the opposite is true:

- Stories make facts memorable. They enhance our cognitive ability beyond the use of language, and make facts about “22 times more memorable”.

- Stories make facts relatable. Well-told stories create empathy through the release of oxytocin, which makes them liable to influence someone to change their mind.

- Stories provide frameworks. Stories allow humans to explore norms, explain why we do what we do, and by doing so provide the meaning behind the facts.

This was reflected in Avey and Desch’s 2014 research, in which they identified what government officials want from researchers: policymakers don’t want facts – they want frameworks which help them understand the world, and make decisions.

The environment

The second level of storytelling is about shaping the environment. To steal an analogy from Lizzie Stanley at Theos Think Tank, it is about “ploughing the soil before you sow the seeds”.

This does not mean taking a political position. It simply means providing meaning to the environment, educating a non-specialist audience – both public and policymaker – about the context of research and policy recommendations.

Answering the following questions:

Who are you? What is your world view? What are your values? What is your version of history? How did we get to where we are? What is your vision of the future? What are the competing narratives? What is up for discussion? What are the key sticking points?

This requires being open about why our organisations exist, and what we stand for. It’s a challenge which any organisation which has been through a standard brand exercise – e.g. Values-Mission-Vision-Purpose – should be able to answer with ease.

Talking Purpose

There is a direct read-across between the process of self-reflection that think tanks are undergoing right now, and the process of self-reflection that the corporate world has undergone over the last 15-20 years.

Encouraged by a generation of millennials who place values and purpose high in their list of expectations, many companies have been thinking about their role in society. (These drivers of millennial attitudes have been well documented – here, here and here for example).

This development has spawned a significant corpus of thinking around the topic of ‘Purpose’. Essentially, purpose is about two things:

- Recognising that your organisation has a role to play in society.

- Standing up for your organisation’s values.

Many in the corporate world have recognised that this involves becoming less self-centred (e.g. less reliant on corporate announcements), and talking about bigger issues than themselves. Some more successfully than others.

For the time being, many think tanks are communicating with one hand tied behind their back – stuck in a paradigm where communications are mainly announcement-driven and project-based (i.e. the promotion of the latest research or event), and their values are barely acknowledged, externally at least.

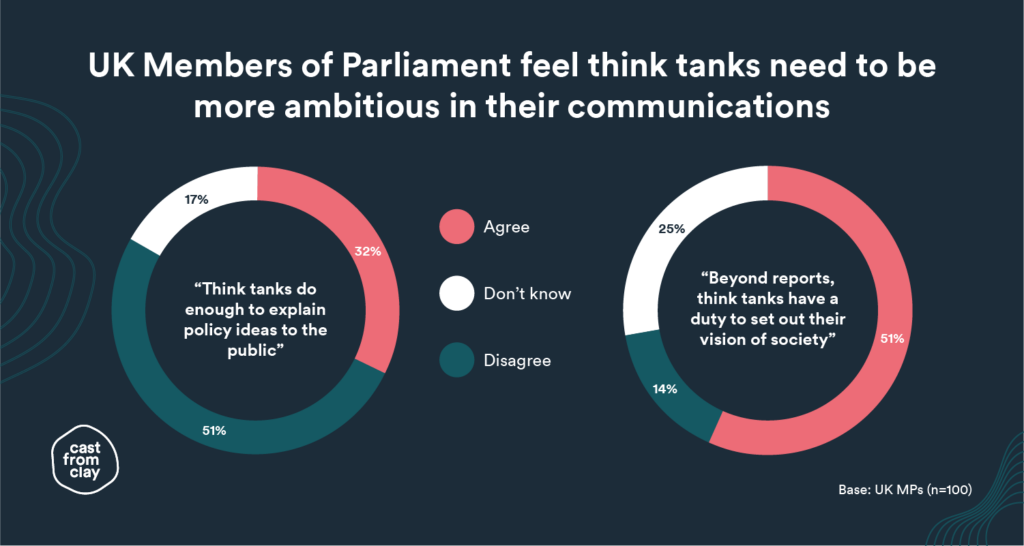

For think tankers who feel uncomfortable about how this direction of travel might impact their relationships with their key audiences, we asked UK MPs what their expectations of think tanks were.

To questions about i) whether there was a role for think tanks to play in educating the public, and ii) whether think tanks should be expected to set out their vision of society – the answer was yes. (We have no reason to believe it would be significantly different in the US, though would love to know if similar data exists.)

Next time…

Having laid the foundations (defined the terms), built the frame (recognised values and assumptions), installed the walls (contextualised research) – we can start designing the interior.

The next blog post will look at some practical steps think tankers can take to approach storytelling, starting with story mapping.

Read Part 4 here