Two years ago, our blog posts proposing a new communications model for think tanks seemed to hit a nerve. Since then, many have been in touch for advice on how to take the first step into storytelling.

This is an ongoing topic of conversation: What does storytelling look like for think tanks? How do you turn a report into a story? Here is our attempt to shed some light on the issue. It’s a 5-part blog – and we’ve approached it much like building a house:

The Think Tank Storytelling Series

1. Laying the foundations > Defining the terms | Part 1

2. Building the frame > Recognising values and assumptions | Part 2

3. Installing the walls > Research in the world of story and narrative | Part 3

4. Designing the interior > Mapping your story | Part 4

5. Picking the furniture > Features of storytelling | Part 5

This is our fifth and final blog in the series.

Features of storytelling

It’s not just about telling a story – it’s also about making it a good one. In this blog, we focus on four key features: relatable language, identifying the characters, tapping into the unconscious, and appealing to the senses.

Relatable language

At its most basic, storytelling conveys meaning through language that readers, listeners or viewers can relate to. While the absence of jargon is a great start, it does not in itself constitute storytelling. It is about creating empathy.

In American Journeys, the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) explored how immigration shapes American identity. There are many reasons which make this a shining example of storytelling – but a key one in our mind was the bold decision to present it as a first-person account, which makes it read like a deeply personal experience.

Meanwhile, Chatham House’s Tribes of Europe took a different – though related – approach. The findings of the research are well-written but ultimately standard think tank fare. What makes this a successful example of storytelling is the fact the reader is drawn in by personalised results, having answered eight questions written in simple English.

Language is also about creating emotional resonance through framing. In 1994, Newt Gingrich’s Contract with America explored how Republican candidates could connect with voters and frame issues through clever turns of phrase. “Tax cuts” became “tax relief”. “Foreign investment” became “international investment”.

The book provided a blueprint for Republican communications, and still shapes it to this day. Our point is not to engage in politically-divisive language. But we are saying that Contract with America showed the power of the language you use to frame the conversation.

Identifying the characters

As we set out in the first blog post, stories are about people, what happens to them, and their relationships. Potential characters include:

- The people impacted by the policy or issue in question.

- The public in general.

- Past politicians or policymakers who have shaped the current policy landscape.

- Current politicians or policymakers who will shape the policy outcome.

- Charities, campaigners, and activists.

- The author of the research.

- Commentators and experts.

Typically, the human-interest angle is ‘covered’ by talking heads – i.e. the last two bullets – who tend to have the least first-hand experience of the issue.

While this is a start, it does little to convey the humanity of real-life situations. We would like to see more of the following:

- Case studies, photo-albums or video/audio interviews of people affected by the issue (anonymised if necessary).

- Edited video clips of, or simply links to, news reports showing interviews of the people affected by the issue.

- Real-life quotes from people affected by the issue.

- Interviews of frontline workers, charity workers or campaigners.

- Vox-pops exploring public awareness or attitudes to the issue.

- Biographic content about key political figures of the past.

- Interviews with historians to position the issue in its historical context.

- A first-person account by the author – not of the findings, but their personal journey researching the issue, the slow realisation or the light-bulb moment.

The objections to obtaining real-life stories are always the same: how do we get access to these real-life people? Why not ask those you interview? Many will be happy to go on the record, and if not there are many ways to anonymise their accounts.

Last month, Theos Think Tank featured real-life stories for the release of their ‘Growing Good’ report. This is not expensive to produce. In fact, it is a lot cheaper than many of the costs associated with a report launch.

Even the OECD has experimented with partnering with four YouTubers, to take a message about corruption to young people in Greece (the ‘environment’ level of storytelling). This approach – on a shoestring budget – generated millions of video views, 62,000 reactions, and won the OECD a social media award in Greece.

The point is, none of these barriers are insurmountable with a little planning, imagination – and most importantly, the desire to put humans back into policy.

Tapping into the unconscious

The reasons humans respond to stories is not entirely clear. What is clear is that it is an unconscious reaction to a pattern. It is about how our brains are wired. And once again, this is as true of policymakers as it is of the general public.

We tend to default to word-based storytelling. But think about other means of telling a story – photography, painting, or music for example. Our brains intuitively recognise peacefulness, despair or elation without the need for words.

Music is a particularly useful analogy. We recognise harmony or dissonance at a fundamental level, we sense growing tension, and we crave the resolution of a musical phrase by coming back to the same note.

This pattern-seeking might also explain why there are said to only be seven different story arcs. And every (good) story ever told seems to be a variation on one or more of these. (For more on this, read Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots.)

The Leave campaign in the UK and Donald Trump’s Presidential campaign – both clearly drew on these story arcs: primarily ‘Overcoming the Monster’, and arguably ‘The Quest’.

They portrayed plucky UK and US citizens – not themselves – as the heroes overcoming the odds to defeat the might of the urban middle-class establishment. Where the Remain campaign and the Hillary campaign promised the status quo, those campaigns provided a happily-ever-after.

In the Political Brain, Drew Westen explains that the success of political messaging often rests on activating pre-existing neural circuits – through words, imagery, metaphors, analogies, music. The aim is to create unconscious associations in our brains.

Think tankers are starting to wake up to the power of the unconscious. Only a few weeks ago, the International Centre for Migration Policy Development published a report calling for migration experts to recognise the role of values in their audiences, and speak to them accordingly.

Richard Darlington also talked about this in an address to the Norad Conference, in the context of international aid.

The implication is that this approach requires a sophisticated understanding of your target audience – their level of knowledge about the issues, their attitudes towards it, their frames of reference, their unconscious biases, etc.

The kind of understanding which can only come from audience research.

Appealing to the senses

Storytelling can take many forms. As a sector, we default to a format – text – which may appeal to the conscious, rationalistic part of the author’s brain, but which restricts us in terms of everything else.

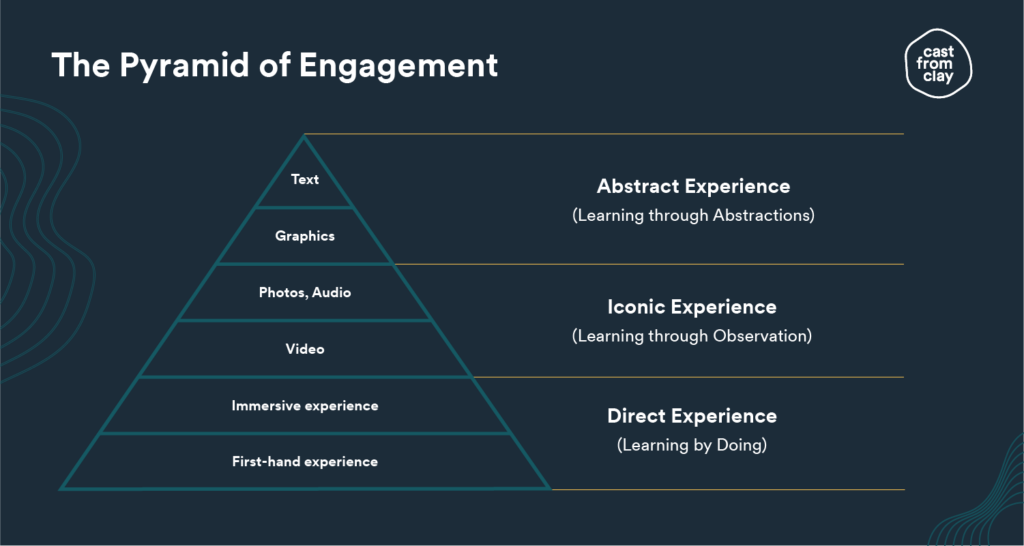

In recent years, we have at least recognised there is a hierarchy of engagement formats. The following graphic is inspired by American educator Edgar Dale’s famous Cone of Experience visualisation, which sought to illustrate how people learn.

As you progress upwards through the pyramid – from first-hand experience to text – the degree of abstraction increases. And audiences go from being participants to being spectators.

The bottom of Dale’s cone represented “purposeful experience that is seen, handled, tasted, touched, felt, and smelled”. By contrast, at the top of the pyramid, words are more remote.

We’ve experimented, a little. But our experimentations – in image (e.g. graphics/infographics), video (e.g. talking heads) and audio (e.g. podcasts) – still instinctively try to appeal to the conscious, rational part of the brain, and nothing else.

Can we move beyond this model? Here are a few ideas about how we might appeal to the senses, and in doing so tap into the unconscious.

Visual

We’re all familiar with visual storytelling by now. In our world, visual storytelling tends to be led by data – infographics, data visualisations, maps, etc.

While many excellent examples of these spring to mind (and a few bad ones), on their own they tell a very one-dimensional story. The data story. But not the human story.

We’ve given examples of possible video, audio or image content above – so we won’t labour the point. It’s about telling a more rounded story overall.

Auditory

Clever use of audio can help bring a story to life. Again, ODI’s American Journeys remains one of the few examples we have seen to do this – and yet with minimal effort, it succeeds in creating a connection with the humans behind the policy.

Beyond audio interviews, music is an obvious way of tapping into your audience’s unconscious to reinforce a message. Political campaigns have been using popular songs going all the way back to John Adams in 1800.

From Donald Trump’s use of You Can’t Always Get What You Want by the Rolling Stones to George H.W. Bush’s use of This Land Is Your Land by Woody Guthrie, via will.i.am’s putting Barack Obama’s Yes We Can speech to music – politicians have leant on music to convey the story of their campaign.

This is just as true in the UK, where Tony Blair’s use of Things Can Only Get Better by D:Ream for his 1997 campaign remains one of the most iconic moment in British politics, while It’s Maggie For Me remains a memorable British campaign song.

But it’s not just about the lyrics. Instrumental music can help reinforce a message, or draw on a certain mood or emotion. And there are a number of websites which offer music under a Creative Commons licence. Here are just a few which allow you to search for pieces by artist, or by mood: Audionautix, Musopen, Incompetech, Scott Buckley.

(Note: Some websites provide music under a mix of licences, so please check before you use it – and remember to credit the author.)

Immersive

Depending on whether immersive experiences are virtual or real-life, they can be more vivid visual/auditory experiences, or they can appeal to all the senses. These experiences are particularly effective for educating and influencing politicians and policymakers.

There aren’t too many examples of this in our sector, so we’ve taken inspiration beyond the sector. Two examples stuck in our minds.

The first was a virtual experience designed to give (male) participants first-hand experience of what gender inequality looks like in the work place.

The second was a real-life exhibition at the European Parliament in which participants (MEPs) played a game designed to explain the length and investment of the drug development process.

Sense of wonder

While wonder is not an actual sense, it is important to reflect that there is a special place for beauty and elegance in storytelling.

A study by Shareablee – a social data company – in 2015 found that good storytelling was one of the four major drivers of content sharing on social media.

We still love ‘It’s a Wonderful Loaf’ – an incredible example of educative content about how the free market works by PolicyEd, a Hoover Institution initiative. Quite simply, beautiful storytelling.

Cast From Clay’s Five Principles of Storytelling for Think Tanks

That’s it for now. Thank you for joining us in this 5-part blog series, and congratulations for making it so far!

We’ve thought long and hard about how to distill all of this into a few key principles. And we’ve boiled them down to the following:

This is as pithy as we can make them, though I’m sure we can do better. In the meantime, let us know what you think!