This is an ongoing topic of conversation: What does storytelling look like for think tanks? How do you turn a report into a story? Here is our attempt to shed some light on the issue. It’s a 5-part blog – and we’ve approached it much like building a house:

The Think Tank Storytelling Series

1. Laying the foundations > Defining the terms | Part 1

2. Building the frame > Recognising values and assumptions | Part 2

3. Installing the walls > Research in the world of story and narrative | Part 3

4. Designing the interior > Mapping your story | Part 4

5. Picking the furniture > Features of storytelling | Part 5

This is our fourth blog in the series.

Mapping your story

Now, time to get into the mechanics of storytelling. So, first off the bat: a one-off report launch, commissioned with 2 or 3 weeks’ notice, cannot possibly convey a story.

A story requires tension to build up. This is not possible to deliver with what Richard Darlington calls the ‘submarine strategy’: i.e. researchers submerging into an ocean of data and re-surfacing 6 months later with all the answers.

Storytelling requires planning.

The standard model of storytelling

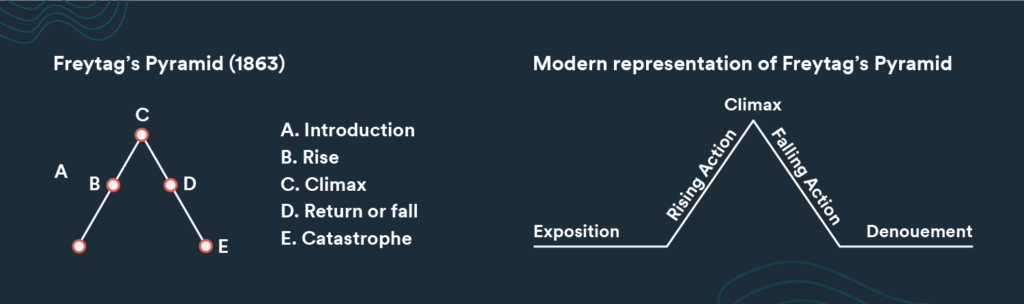

All stories have an arc, which plots the action from beginning to end. The most enduring model has been Gustav Freytag’s ‘Pyramid’ model.

Freytag identifies five parts to dramatic structure:

- The ‘Exposition’ phase sets the scene – the status quo – and introduces the characters (including the protagonist), describes how they relate to each other, and what is at stake.

- The ‘Rising Action’ phase starts with a conflict which induces the protagonist to take action, and charts the events building up to the climax – typically including some minor challenges which the protagonist must overcome.

- The ‘Climax’ phase is the high/turning point of the story, where the protagonist engages with the adversary and makes the crucial decision on which the outcome of the story hinges, and which will also define the protagonist’s moral quality.

- The ‘Falling Action’ phase typically charts the events that result from the big decision in the climax phase, in which characters’ actions typically resolve the problem (or don’t in the case of a tragedy).

- The ‘Denouement’ phase shows the fallout of the previous phase – the conflict has been resolved one way or another, and the new status quo takes over, but the events often give the protagonist a new outlook on the status quo.

Story mapping for think tanks

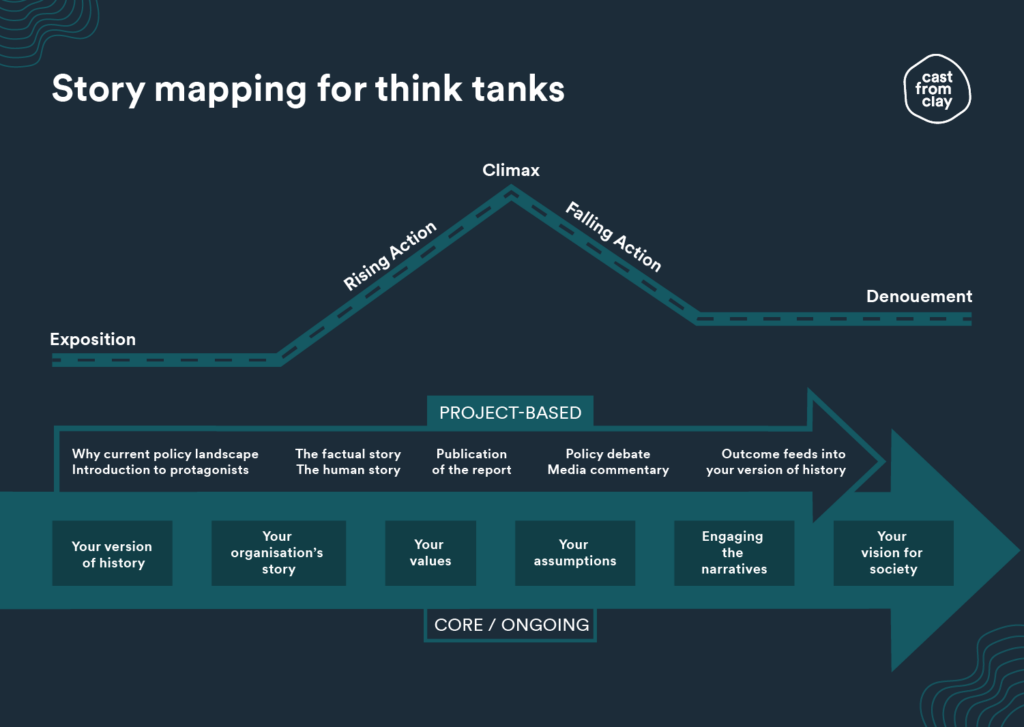

Understanding how stories work gives us the opportunity to plan ahead.

If we consider the report publication as the climax, what does the build-up phase consist of? What happens after the report publication? Did we set the scene in the first place as a benchmark? What is the outcome?

We’ve suggested below what this might look like, building on Freytag’s model and applying it to typical think tank communication activities.

Exposition

This phase is about laying the groundwork ahead of the report. Setting the scene while the research is underway allows us to frame the conversation. This might involve reminding policymakers and the public about the challenge, the current policy landscape, how we got here, and introducing the protagonists.

In our last blog, we argued think tanks should engage in shaping the environment – talking about their values, their version of history, their vision of society. In this world, setting the scene is already done through ongoing communications, with only minor adjustments required for the topic in question.

Rising Action

This phase is about ramping up activity ahead of the publication of the report. Seeding facts, releasing previews. And importantly, seeking to tell the human side of the story, as well as the factual or statistical. (More about how to tell human stories in the next section.)

Unlike the previous phase, this signals a departure from ongoing communications, and a launch into project-based communication.

Climax

We’ve assumed that the release of the report is the climax – the point at which the main protagonists are typically presented with a choice.

This should be more familiar territory for think tanks.

Falling Action

This phase is about the fallout from the climax. We’ve suggested it might consist of the policy debate that ensues, media commentary, and the like. But the reality is that this phase will stretch beyond the media engagements at launch.

This might prove to be the most challenging phase, as it is the point when thinktankers typically disengage and move on to the next project. Until funders see the deliverable in terms of impact (e.g. reframing the debate, policy adoption) rather than outputs (e.g. the report), this will remain a challenge.

However, this is easier to address if your think tank is engaged in ongoing communications.

Denouement

This phase is the resolution we all seek as humans, and which we are often denied. It is about the outcome. What happened in the end? Was the policy adopted? If not, which policy was adopted?

This outcome should feed straight back into the ongoing communications serving to shape the narrative. What is the happily ever-after? How does it affect your version of history?

Learning from the alt-right

This approach, of course, requires planning. Storytelling is something the alt-right have been spectacularly successful at over the last few years. Back in 2015, a Bloomberg profile of Steve Bannon gave us a little insight into how they work.

Bannon founded the Government Accountability Institute (GAI) in 2012 to investigate cronyism in politics – and most particularly, Hillary Clinton’s financials. Set up as a nonpartisan charity, the research organisation is described as being set up “more like a Hollywood movie studio than a think tank”.

GAI is set up more like a Hollywood movie studio than a think tank

The creative mind charged with turning “dry think-tank research” into “vivid, viral-ready political dramas” is celebrity ghostwriter Wynton Hall. His team works very long and hard to build a narrative, storyboarding it out months in advance.

“Every time we’re launching a book, I’ll build a battle map that literally breaks down by category every headline we’re going to place, every op-ed [GAI president Peter Schweizer] is going to publish. Some of it is a wish list. But it usually gets done.”

Whatever we think of the alt-right, it is undeniable they have shaped the political narrative. Joe Biden’s presidential victory does not signal the end of Trumpism – almost half of the US population voted for the incumbent president. This is not over.

Populists they have framed the debate for years to come. They have done so by skilful storytelling – weaponising data and crafting long-term narratives. We can, and should, learn from how they did it.

Next time…

Having laid the foundations (defined the terms), built the frame (recognised values and assumptions), installed the walls (contextualised research) and designed the interior (mapped the story) – it’s time to pick the furniture.

Our fifth and final blog will look into the attributes of storytelling, and how thinktankers might start tapping into these.

Read Part 5 here