This is an ongoing topic of conversation: What does storytelling look like for think tanks? How do you turn a report into a story? Here is our attempt to shed some light on the issue. It’s a 5-part blog – and we’ve approached it much like building a house:

The Think Tank Storytelling Series

1. Laying the foundations > Defining the terms | Part 1

2. Building the frame > Recognising values and assumptions | Part 2

3. Installing the walls > Research in the world of story and narrative | Part 3

4. Designing the interior > Mapping your story | Part 4

5. Picking the furniture > Features of storytelling | Part 5

This is our first blog in the series.

Defining the terms

In trying to describe what think tank storytelling means, we found ourselves limited by language. For instance, people tend to use a number of terms interchangeably – story, narrative, framework, plot – without having defined what they mean, or how they differ.

We found that we needed to start with a common frame of reference. This first post seeks to define a few key terms – and in particular the relationship between story and narrative.

Stories versus narratives

A story is about people, and the things that happen to them. It is made up of multiple facts and events (the plot) – but most importantly it involves characters, relationships, and how they evolve.

The story might be about Jonathan, who saw the cuts to his disability benefits as a result of recent welfare reform, and is now struggling to provide for his family.

Or Luisa, whose cleantech business is now booming thanks to new environmental subsidies, after years of adversity and hard work.

The narrative is the framework within which the story is told. It is a subjective sequencing of events – and the relationships between them (the arc) – with a view to providing meaning. These parameters shape how the story is interpreted.

Jonathan might see the cuts to his disability benefits as evidence of the systematic dismantling of public services over the last 30 years.

Meanwhile, Luisa’s narrative might centre on the inevitable shift towards a zero-carbon economy.

But narratives, being subjective, are often personal. One person’s narrative can be at odds with another person’s narrative. And two competing narratives can draw different conclusions from the same story.

Where Jonathan sees persistent cuts targeting the most vulnerable, Sarah might see a necessary rebalancing of the national budget after years of irresponsible spending.

To Luisa’s assertion that she is on the right side of history, Graham might retort that the green lobby’s victory is propping up an industry incapable of standing on its own two feet.

While stories typically have a beginning and an end, narratives are usually ongoing. There is a predictive quality to narratives, in that they have a direction of travel.

Narratives are shaped by stories

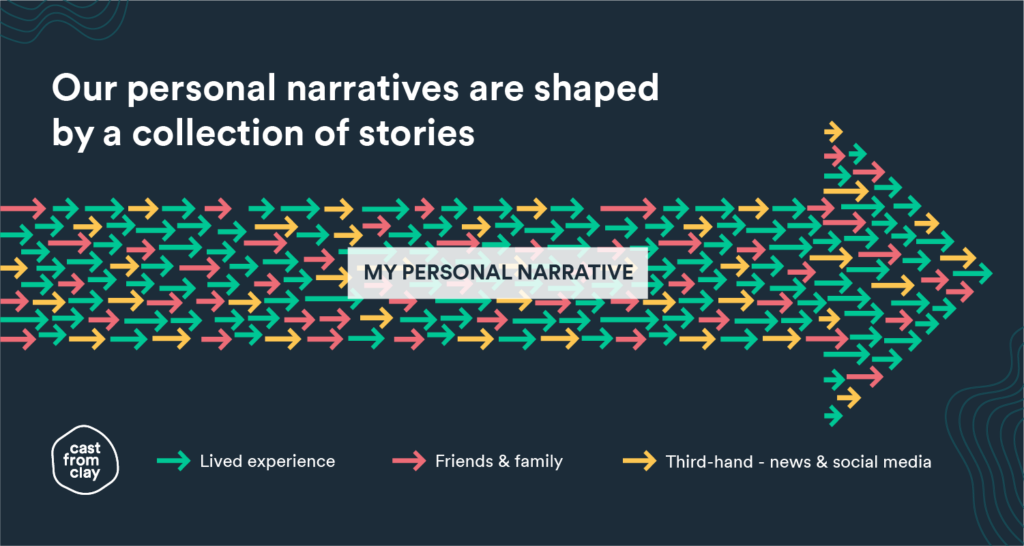

Narratives usually evolve organically in people’s minds, from a multitude of stories.

We all have our own collection of stories – from the cautionary tales of our childhood, to our own lived experiences, to our friends’ and families’, to the ones we observe second- or third-hand in the media or on social media.

And we all have our own narratives – rooted in our personal or community’s values, shaped by our own stories. This is just as true of policy makers as it is of the wider public.

Critically, two distinct topics may each have their own narrative in people’s minds, which will co-exist even though they are at odds or even fundamentally incompatible.

Ken may believe that the state has become too involved in people’s lives for example, while also thinking social services should do more to protect children at risk.

But while we each have our own individual narratives, they are often variations on a single prevalent collective narrative – whether contextual (e.g. Democrats/ Labour are the party of tax-and-spend, Republicans/ Conservatives believe in small government), or foundational (e.g. the American Dream in the US, the Republic in France).

That narratives are based on a multitude of stories explains why they are incredibly hard to change.

A single story that contradicts your narrative will not invalidate that narrative – because a narrative is typically grounded in many other stories, which people filter in or out (i.e. curate) over time to reinforce that narrative. This is often referred to as confirmation bias.

Changing the narrative

Since narratives are so hard to shift, they are typically replaced only as a result of transformational – often traumatic – events. These events bring to bear the fact that the narrative clearly and vividly no longer fits the reality.

At a personal level, this could be a relationship breaking down, a medical condition deteriorating, or a business going bankrupt.

At a societal level, transformational events in modern history have included the World Wars, the Wall Street Crash, the Suez Crisis, the Vietnam War, 9/11, or the financial crisis of 2007-08. The COVID crisis is almost certainly going to be another.

There are also instances where sustained large-scale communication campaigns have changed the narrative. The UK government’s Every Mind Matters campaign, for example, changed the narrative around mental health. Black Lives Matter and the #MeToo movement offer examples of more grassroot campaigns which changed the public imagination.

Great political communicators have always been able to reshape the narrative. In recent history, the likes of Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, Tony Blair, Angela Merkel, and now Donald Trump changed the narrative within their respective countries.

These leaders all identified a critical moment in time, when their country was ripe for a new narrative, and seized it. They were able to help a nation make sense of millions of lived-experience stories, through a narrative which coherently bound these stories together.

Importantly, they each in their own way connected with the electorate at a human level, and replaced an old moribund narrative which no longer rang true, with a new one. A shift in narrative will always bring with it the prospect of change and hope.

When leadership fails

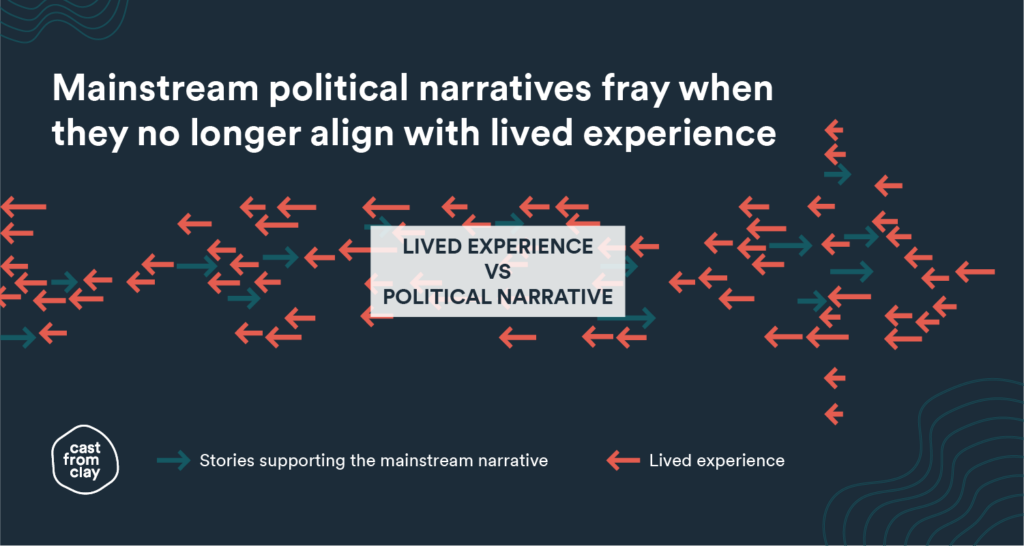

In the absence of such catalysts, narratives simply evolve over time, refining themselves organically among the population to reflect the new realities of the times.

If the political class doesn’t shape these changes in narrative themselves, they need to at least reflect them. Where lived experience is at odds with what the political class is preaching, the prevalent narrative frays and eventually disintegrates.

This was the case in the Soviet bloc at the turn of the 1990s. We’re seeing this in Belarus. And we have also seen signs of this happening across Western societies in the last five years.

Next time…

Having laid the foundations by defining the terms, we move on to building the frame. The next blog post will look at two additional concepts – values, and assumptions – which go a long way to explain why certain narratives gain traction over others.

Read Part 2 hereIf you need help implementing this in your organisation, we can help. Get in touch.