This is an ongoing topic of conversation: What does storytelling look like for think tanks? How do you turn a report into a story? Here is our attempt to shed some light on the issue. It’s a 5-part blog – and we’ve approached it much like building a house:

The Think Tank Storytelling Series

1. Laying the foundations > Defining the terms | Part 1

2. Building the frame > Recognising values and assumptions | Part 2

3. Installing the walls > Research in the world of story and narrative | Part 3

4. Designing the interior > Mapping your story | Part 4

5. Picking the furniture > Features of storytelling | Part 5

This is our second blog in the series.

Recognising values and assumptions

In addition to the terms we defined in Part 1, it is worth defining these two terms. For the simple reason that they go a long way to explain the traction of certain narratives.

Values

Values will make individuals, groups, organisations and societies more readily pre-disposed towards one narrative or another. Values might be inculcated by family, social class or cultural group – and there is also growing evidence that genetics play a role.

The interplay between values and narratives is worthy of a blog post in its own right, so we won’t explore this here. We encourage readers wishing to explore this further to read up on Haidt’s ‘Moral Foundations Theory’ and Schwartz’s ‘Theory of Basic Human Values’.

Such theories are increasingly influencing the thinking on partisanship and polarisation in the US, and on communicating about politically sensitive issues such as migration.

The Narrative Initiative uses the metaphor of ‘Waves’ to explain how narratives work. It talks about messages and stories as waves, generated by currents below the surface (narratives). In this metaphor, values and world views represent the deep undercurrents.

Another way of characterising the relationship between values and narratives is to think about software. If we think of narratives as software – and individual stories as software updates – values are the operating system.

The key to this metaphor is compatibility. If a narrative only speaks to one set of values, it simply won’t run on other value systems and will be ineffectual as a result.

Assumptions

Meanwhile, assumptions are foundational notions which we – as people who work in politics or policy – hold to be so self-evident and universal that we no longer mention or question them.

Or worse, we don’t even recognise the validity of the question when it is legitimately raised by others. This is often referred to as conventional wisdom.

This is a phenomenon which those working in the Beltway or Whitehall bubbles are particularly vulnerable to. Think tanks, among others, find themselves at risk of forgetting that the assumptions on which their work is premised are not irrevocable universal truths.

These assumptions suggest a certain view of the world – urban, educated, middle class, liberal – which has been largely unchallenged since WWII, but relies heavily on the public’s continued support. And it worked fine while a critical mass of the population was happy.

However, we have increasingly seen a number of conventional wisdoms challenged by the public over the last few years (some more effectively than others). These include:

- Globalisation: “Overall, globalisation has been beneficial for the world.”

- Multilateralism: “Co-operation is the best way to maintain security and prosperity.”

- Free trade: “Removing barriers to trade makes everyone involved more prosperous.”

- Growth: “Economic growth is everyone’s number one priority.”

- Equalities: “Every hard-working citizen deserves equal opportunities.”

- Welfare state: “People deserve a safety net to protect them from hard times.”

- Fiscal responsibility: “Governments must maintain sustainable public finances.”

- Human rights: “All humans have inalienable rights.”

- Separation of powers: “The legislative and the judiciary need to balance out the executive.”

- Representative democracy: “The legislature reflects the people.”

The shift from alternative narrative to mainstream

The public’s explicit and implicit questioning of previous assumptions can be seen by the growing traction of alternative narratives, which would have been considered fringe views only a few years ago. Today, everything is back on the table.

As an example, we asked the UK public earlier this year how they felt about a number of democratic principles we take for granted:

- Barely 50% of the UK public agrees that freedom of speech is more important than economic growth.

- 30% of the UK public thinks government should be able to bypass Parliament to get their policies approved, and a worrying 50% of ‘Insiders’ – i.e. those who work in politics or policy – agree.

No longer the preserve of fringe groups, the alternatives have influenced, and in some cases even been co-opted into, mainstream ruling parties (e.g. protectionism, state interventionism, anti-multilateralism, to name but a few).

And for this reason, they are no longer valid assumptions. They are battlegrounds in the so-called culture wars. Where you stand on these ideas has increasingly become a point of identity. This needs to be recognised by Whitehall and the Beltway.

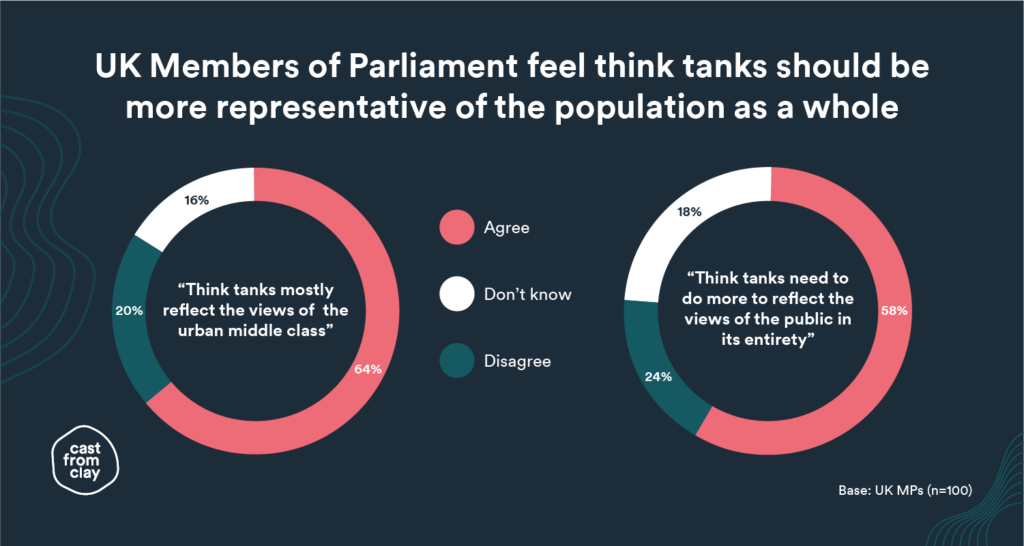

Earlier this year, we asked UK MPs whether they felt think tanks did a good job of representing the views of the population. The answer was pretty clear. (And we have no reason to believe the answer from Congressmen/women in the US would be any different.)

This does not mean think tanks need to entertain or reflect populist views. But this does mean they have to recognise alternative narratives – by virtue of the fact some of them have traction among the public – and engage them in a meaningful way.

We need to make the case

Our conclusion is this: we all need to check our assumptions, and make the case for the values and principles we have taken for granted. We collectively have a role to remind ourselves of how we got here, and to frame the public conversation within its historical context.

This responsibility does not just fall on the shoulders of think tanks, of course. But in this highly polarised environment, can we rely on politicians or the media to carry out that role? Who is better placed to do this than the champions of evidence-based policy?

For all think tanks’ desire to be seen as apolitical, dismissing alternative narratives is de facto taking a political stance. Think tanks will be – and to some extent already are – seen as having picked one side, and ignoring the other.

And in turn they will be dismissed by the side they’ve ignored. At a time when alternative narratives are influencing the destiny of many countries in the West, this feels like a dereliction of duty.

Purpose, not partisanship

Think tanks’ reluctance to have an opinion is often rooted in two factors: 1) placing a moral value on objectivity, and connected to this, 2) a fear that the integrity of their research will be undermined by perceived partisanship.

To be clear, this is not an argument for think tanks to become party-political. This is an argument that all think tanks are inherently political (not ‘party-political’). At the most basic level, evidence-based policy requires a functioning democracy, for example.

And then each sector has its own political values. Any serious organisation researching climate change or pandemic preparedness needs to believe in multilateralism at some level. Any organisation researching benefits policy needs to believe in welfare at some level.

The point is that many think tanks – in particular those who align with the old political ‘mainstream’ – go to great lengths to avoid talking about political values, even though these values are in their DNA.

Meanwhile, those think tanks who are open about what they stand for, find it significantly easier to tell their stories. Why? Because storytelling is inherent in their positioning. They already have a framework within which to tell their stories – which makes it easier for them to make the case for the funding to tell these stories.

Next time…

Having laid the foundations (defined the terms), and built the frame (recognised values and assumptions), we turn to installing the walls.

The next blog post will look at the role of storytelling in the context of research, and the two levels of storytelling which think tanks should be considering.

Read Part 3 here