How to position a think tank

Many think tanks over-rely on practicalities in their positioning. One way this manifests is a focus on research, ignoring firstly that research in think tanks is a means to an end, and, secondly, that every think tank conducts research.

Think tanks do not conduct research for research’s sake, unless they are staffed by academics trapped in think tank livery. They exist to achieve outcomes, not simply create outputs.

‘Research’ is just one of a host of words used in positioning statements that fail to differentiate think tanks from their peers and competitors. Other repeat offenders include:

“We find solutions to difficult problems.”

Think tanks by definition find solutions to difficult problems. It is something all of your peers claim, too.

“We come up with big ideas.”

The same as solving difficult problems, reframed.

“We are independent.”

From funders? Perhaps, but few believe it.

The best positioning statements clearly differentiate an organisation from its peers and competitors, encapsulating both a thematic focus, and a statement of values.

Without the thematic focus, your organisation will not have clarity of focus – across research, communications, and development. You will not develop subject matter expertise to your potential.

Without the values statement, you aren’t being clear about what you stand for, or what world you want to create. You’re leaving a gap for people to fill of their own volition.

Thematic think tank positioning

There is a clear difference between small- and medium-sized think tanks versus large organisations.

Large think tanks may have many different practice areas, each the size of a small- or medium-sized think tank. But unlike most smaller think tanks – especially ones that are relatively new – they typically benefit from an established, prestigious brand, built over many decades.

Most small-to-medium think tanks should have a singular clear thematic focus area. Without this focus, it becomes challenging to develop subject matter expertise, and develop the depth of relationships (whether they be media, political or policy) that will allow you to do your best work.

If you work across five areas, for example, and you have a comms team of four, your comms team will not be able to achieve the economies of scale than if they were all dedicated to a single focus area. The same is true of your researchers, and the depth of expertise within your organisation.

The goal is not to be the biggest think tank. The goal is to be the most impactful in your area of expertise. You need to specialise in order to do this, and you need to learn to say ‘no’.

If that means siphoning off a research team that doesn’t align with your mission to a more suitable institute where they can carry on their work, then so be it. They will be better for it, and so will you.

Organising your communications function

Edelman, the world’s largest communications firm and my former employer, used to have a department called Edelman Digital. As I was leaving in 2014, this department was divided and its employees split across every other department, from public affairs to consumer.

The company transitioned Edelman Digital to a digital Edelman.

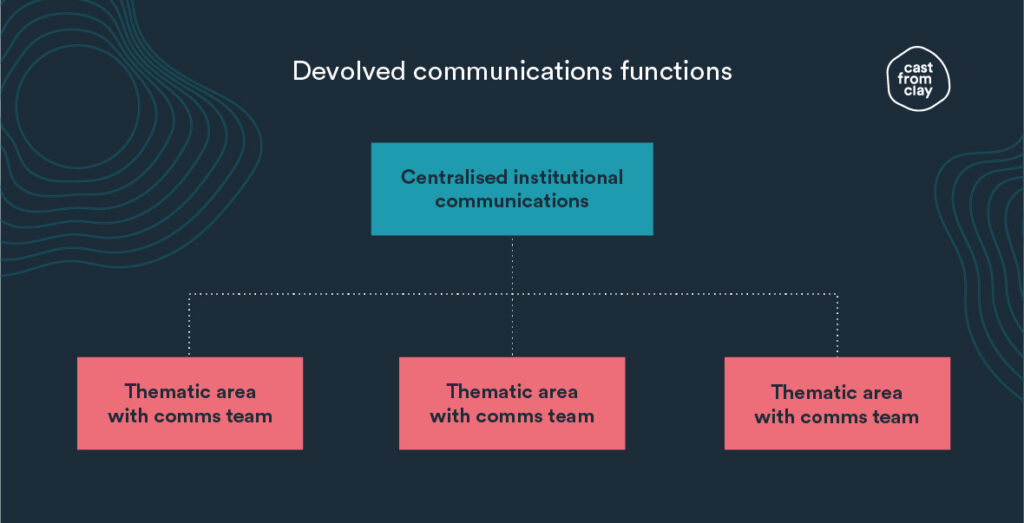

Consider a centralised communications team for institutional communications. And devolved communications teams for thematic communications, embedded within each team. Thus each thematic area becomes its own satellite think tank, leasing the parent brand.

Each of these satellites is able to develop thematically focused expertise and relationships in development, communications, research, policy, politics, etc. This speciality and autonomy will enable it to deliver better outputs and improve its outcomes.

This is not a new idea. Several think tanks adopt this approach already. It makes a lot of sense.

Think tank values statements

Establishing what an organisation stands for is not always an easy task. There are two areas to consider when thinking this through for your organisation:

1. Focusing on instrumental values rather than intrinsic ones.

Instrumental values are those that are valued for what they allow you to achieve.

The act of walking through a forest makes me feel relaxed. It is the same for playing guitar, and cycling. Doing each of these things has instrumental value to me; by doing each, I attain something else.

Intrinsic values are those that are valued for their own sake.

I value feeling relaxed purely to feel relaxed. I don’t do it to achieve anything else.

When thinking about your values statement, look for the intrinsic ones. These could be socio-economic equality, freedom of thought, or inclusivity. Yes, they may have direct benefits, but your support of them is likely to be much more foundational to you. It isn’t because of what they achieve that you support them, but because you believe it to be morally right.

On the other hand, the value of objective research is an instrumental value (if it means anything). It allows you to achieve something else. A more informed legislature. A better educated public. A more liberal economy. That something else is what you want to be focused on. That is your goal – research objectivity is just how you get there.

2. Choosing values specific to your organisation.

Think of an organisation whose values are antithetical to your own.

If you are the Heritage Foundation, think of the Center for American Progress. If you are the New Economics Foundation, think of the Institute of Economic Affairs.

Can you see your new alter ego publicly standing behind your values?

There is no harm in affirming some universally accepted values in your values statement, but if you find yourself only using universally accepted values it suggests either a lack of confidence in standing up for what you believe in, or a reluctance to be transparent about what you actually stand for.

Values are the lifeblood of culture. They help us define the world we want to create. They help us identify who is in our in-group, and who is not. We all have them, including your audiences: politicians, civil servants, the public.

If you do not transparently communicate your values, others will make assumptions.

The Institute for Government (UK) has a relatively generic set of values: innovative, rigorous, impartial, trusted. Most think tanks can affirm these statements. It describes itself as politically non-aligned, but this is not how it is seen.

Consider this from Brexit campaigner Tom Harwood writing in our Vantage Point series: “the Institute for Government has been seen as having anti-Brexit leanings, with Government figures having noted funding from the campaigning Lord Sainsbury as well as the personal positions of staff on totemic constitutional questions.”

Being clear about your values and what drives you brings clarity to the marketplace. It is an honest recognition that “think tanks are ideological.”

It’s not just about what you stand for, though, as Anne-Marie Slaughter raised in her On Think Tanks keynote, we need to assess what we call ourselves, too.

Moving beyond the think tank

In a world where competition for policy influence is strong, and one where think tanks need to engage broader sets of audiences to have impact, flying under a moniker that people don’t have any relationship with – and if they do it has reputation issues – is worth questioning.

Enrique Mendizabal, founder of On Think Tanks, questioned in his Vantage Point article whether the “[think tank] label may disappear one day.” Think tanks considering how to forge a more impactful brand over the next decade should consider that counsel.

You will not be the first to ditch the term: many organisations that we conceive of as think tanks do not publicise themselves as such.

Consider the two most well known American think tanks, Brookings and Heritage. The former describes itself as a public policy organisation, and the latter as a research and educational institution.

There are a multitude of options: policy organisation, educational institute, campaign, advocacy group, lobbying group, policy organisation, research organisation, or NGO. Anne-Marie Slaughter’s suggestions were ‘civic organisation’ or ‘change hub’. Each has its pros and cons, and each organisation will feel differently about each term and whether it could use it.

From your audience’s perspective, however – the people whose views you want to change, or who you are inspiring to take action – one of these descriptors is probably a more accurate and compelling reflection of what your organisation does than ‘think tank’.

While there are legal and organisational considerations in both the US and the UK when terms such as ‘advocacy’ or ‘campaign’ come into play, concerns about the reputational impact may be unwarranted.

Consider this from a Bloomberg journalist we spoke to:

“Calling yourselves a campaign or an advocacy organisation rather than a think tank would have a negligible impact on trust towards the research. We would rather an organisation be up front about their objectives and funding. Every organisation has a bias – it’s our job to look at the research and adjudicate on that. If they have a reputation for producing good research, that’s the most important thing.”

When rethinking your policy organisation’s positioning, think on three areas:

1. What kind of organisation are you? How do your audiences perceive that kind of organisation? Is it the best description of what you do?

2. What are your intrinsic values? Are they distinct from your peers and competitors? Are they a truthful reflection of you?

3. What is your thematic focus? What are you doing now that you should stop doing tomorrow? What is stopping you specialising?

If you missed Part 1, you can read it here.

If you missed Part 2, you can read it here.