So let us make the case for it.

A new policy dynamic

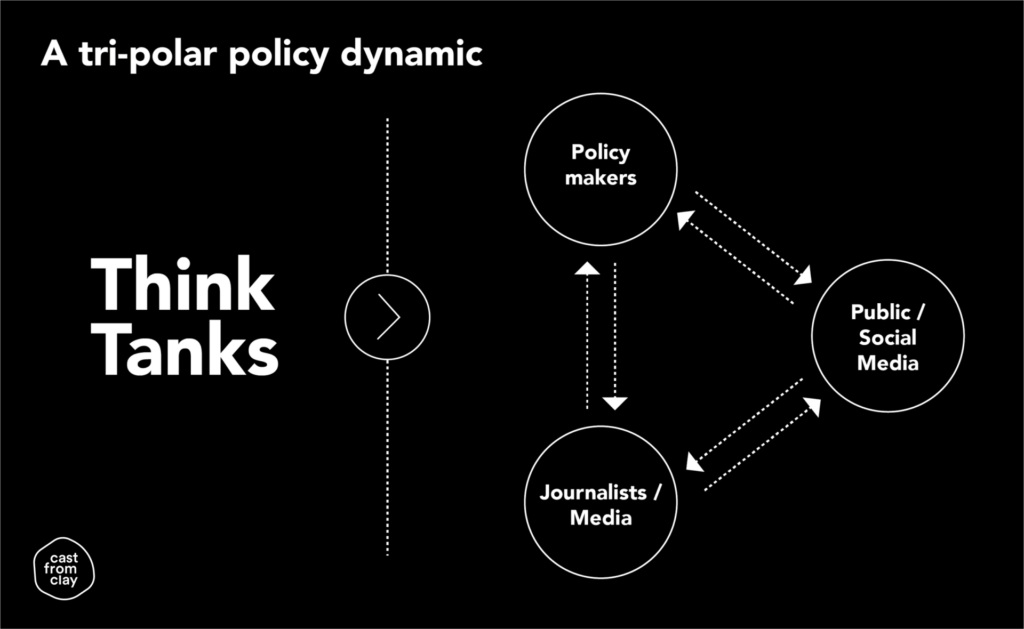

Traditionally, the audiences for think tanks were policy makers and the media. Why?

Up until 10-15 years ago, the policy agenda was set by politicians and the media – and more specifically, the interplay between the two. It was a bi-polar dynamic.

This is not to say public opinion didn’t matter. It most certainly did. Politicians had to take the public’s demands into account, and the media responded to its changing tastes. But the public was not an active player in the policy debate. It was represented by surveys, polls, focus groups, or market research.

Social media has given the public a voice. This voice is undoubtedly messy and noisy. But in aggregate, it carries considerable weight.

As a result, the public has become an active player in the debate. It can coalesce. It can support. It can turn. And – importantly – it has turned that bi-polar dynamic into a tri-polar dynamic.

In the early days of social media, the public was a follower rather than a leader in the online conversation – reacting to politicians, commenting on the news. Today, it is more assertive. It influences politicians and helps shape media coverage, just as much as politicians and media influence it.

If there are any doubts, look at the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, or the gilets-jaunes (yellow vests) in France. So much so that successful politicians have embraced social media and have increasingly been seeking out the public directly, without the need for the media (e.g. Trump in the US, Corbyn in the UK).

Think tanks’ communications need to respond and adapt to this new dynamic, or risk becoming irrelevant. Engaging with civil society groups and media is useful and important, but these are no longer a proxy for engaging with the public directly.

This is not just the case for charitable think tanks, who – as part of their mandate as a charity – have a duty to educate the public. This is true of all think tanks.

What’s at stake?

Without putting policy recommendations into the context of how the public will react to them, can they be considered viable? They haven’t been stress-tested; we don’t know whether it is politically possible to implement them.

Take President Macron’s climbdown on the fuel tax rise, in the face of the social media-powered gilets-jaunes. Yes, arguably this policy was just the straw that broke the camel’s back. However these are the times we live in. The public is polarised, and policy has become high-stakes.

In the UK, a mere 6 months after the General Election, the Conservatives announced plans for a ban on the sale and export of ivory items. Why? Because of a social media groundswell.

Buzzfeed’s political editor Jim Waterson explains: “In the same week that Theresa May did a U-turn on the dementia tax [another social media disaster], several of the most viral stories online were from pro-Corbyn websites angry about the ivory ban, even though no prominent politician had discussed it.”

There are many more examples. It is impossible to have an informed policy debate on immigration without raising the level of public understanding. Same goes for climate change. Criminal justice. Overseas aid. With social media, the public has the ability to influence and skew the debate.

We can carry on pretending it’s not happening. Or we can adapt to the reality of the public debate today.

We must not lose sight that civil society and media – complemented by advertising – were useful proxies for public opinion or public engagement, they were never meant to be replacements. They remain useful tactics. But social media now makes the gauging of public opinion and public engagement at scale possible, and at relatively low cost.

We should be clear: this does not mean untargeted “fire from the hip” communications. Quite the opposite, this means precisely targeted communications.

What we mean by ‘the public’

Communicating to the public has raised eyebrows among some think tankers. This is probably because the term ‘the public’ is not very helpful.

Mass market campaigns are expensive, and beyond the means of any but the best-resourced think tanks. We are not suggesting think tanks – or policy organisations more generally – become full-blown mass media organisations.

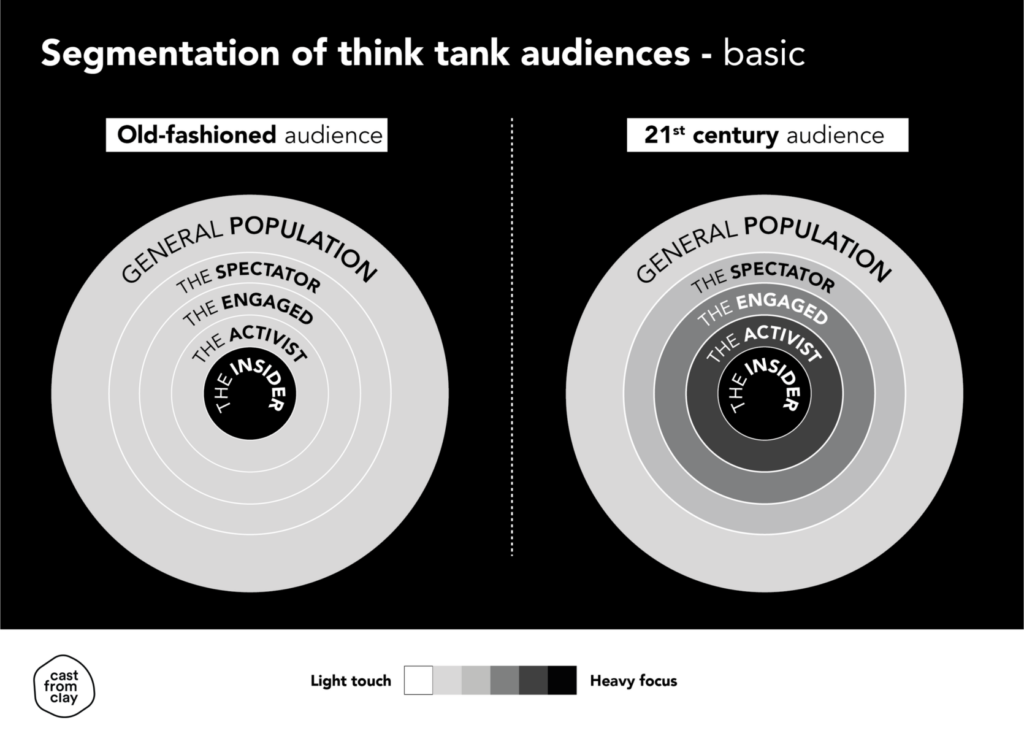

In the research we published last year, we segmented the respondents into four groups, in accordance with levels of political engagement:

- The Insider: People who work in politics/public policy (e.g. politician, elected official, civil servant, regulator, lobbyist, political journalist).

- The Activist: People who are politically active (e.g. party member, campaigner, people who often attend political rallies or conferences).

- The Engaged: People who have taken political action (e.g. contacted my local politician at least once, attended a rally or demonstration at least once).

- The Spectator: People who are interested in politics (e.g. occasionally discuss politics, occasionally share news stories or posts about current affairs).

We should expect some overlap between the groups. Increasingly the ‘Activist’ could find themselves an ‘Insider’, something we have arguably seen with Momentum in the UK or the Tea Party in the US. Similarly an ‘Activist’ can be ‘Engaged’ and also be a ‘Spectator’.

The diagram represents not so much distinct groups, as a ladder of engagement.

Our contention is that think tanks should extend their focus beyond ‘Insiders’, to cover – not the entire population – but the most active and engaged. A parallel is the way in which PR professionals have moved beyond simply targeting journalists, to online influencers.

Communications strategy is about prioritising audiences, and there is much to learn from consumer and corporate marketing here. These approaches are informed by specific communication objectives, and insight into your audience.

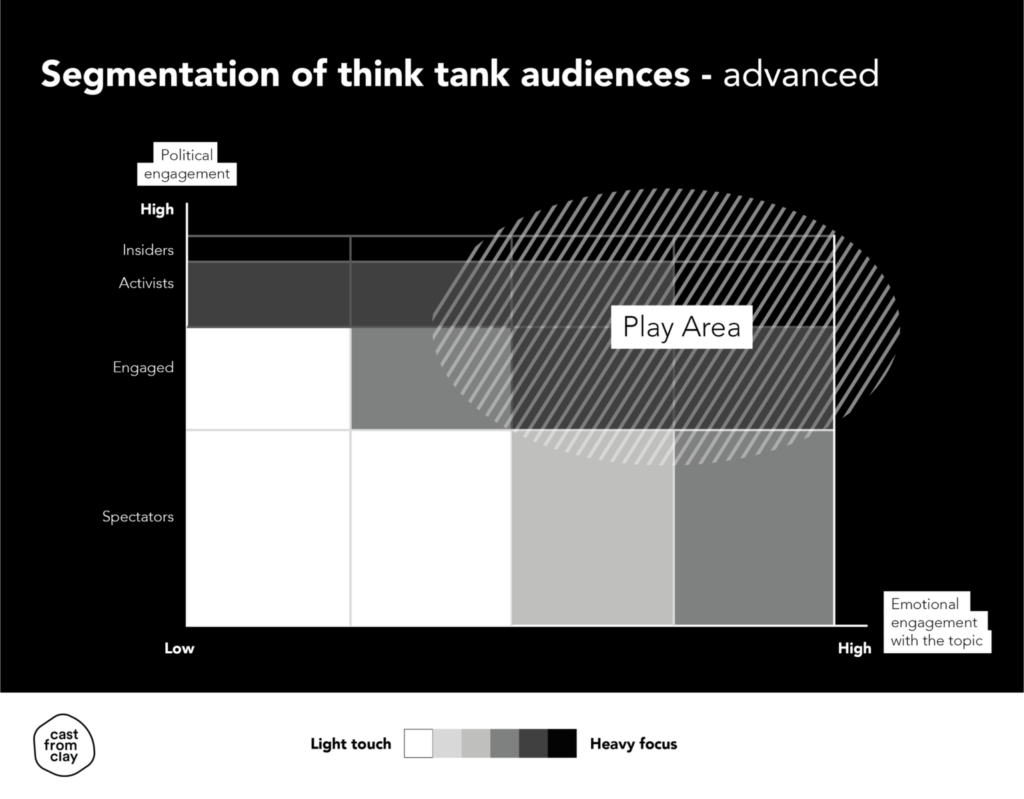

A more sophisticated (but cost-effective) approach would cross-reference levels of political engagement with levels of emotional engagement with the topic.

The top-right quadrant represents where the opportunity lies – the ‘play area’.

Social media makes it relatively straightforward to target these populations today – not to mention the radical reductions in cost to do so compared to what organisations would have spent on ad campaigns in the 1970s.

What this does require is an understanding of these audiences, their media consumption and their online behaviours. All it takes is a little research. This should not be beyond the abilities of the think tank community.