Key findings

1. The public matter as a policy audience – and they expect policy experts to be more proactive

2. If we want to improve public debate, we need to look beyond fact-based communications alone

3. We need to maintain policy influencers’ licence to operate

This data relates to the UK only. You can see the US version here.

Introduction

2018 was a good time to be a populist. The year was marked by the continuing march of this movement worldwide.

The rise of the gilets jaunes in France. The election of Bolsonaro in Brazil. The Five Star Movement and the Northern League in Italy. The continuing assault on democracy in Hungary and in Poland.

In the UK, discussions around identity and immigration remain highly emotional, alongside issues like anti-Semitism, benefits, food banks, homelessness, crime, international aid or climate change.

The Brexit debate has tested the political system to breaking point. No-one has a clear vision of the way forward – but what is becoming painfully evident is that the status quo is no longer an option.

The changes in our politics and in society have prompted think tankers to reflect on their role in the 21st century. Not least of whom Robin Niblett of Chatham House, who suggested international think tanks should be more proactive in promoting the principles they believe in.

Those of you familiar with our work will know that we believe the rise of social media has irrevocably shifted the policymaking dynamic. It has turned the public into an active player that must be taken into account.

Add to this an increasingly active regulator, a probing media, and the backdrop of a new socio-political cycle coupled with a technological revolution – and the scale of the challenge emerges. In this new fluid landscape, what can the public tell us about the role for the modern think tank? We went to Watford, a key marginal seat, to establish the current state of play.

This year’s research sought to explore a number of questions to help our understanding of the political and societal environment within which policy experts operate.

- What are the public’s expectations of policy experts?

- How can policy experts be more effective communicators?

- How have recent events affected public perceptions of accountability?

What we found

A more proactive role for policy experts

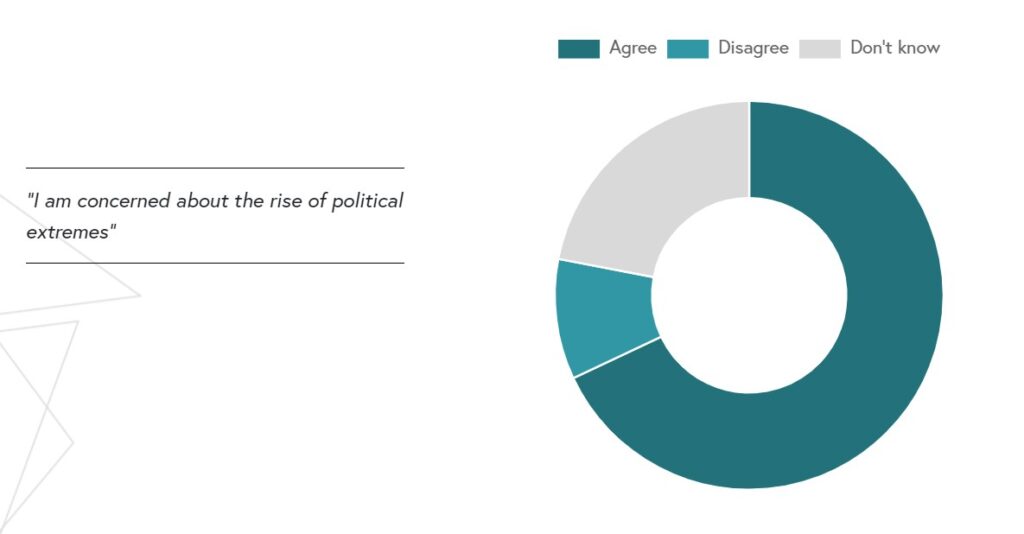

The public want experts to challenge fake news and help them make sense of current affairs. Those that are afraid of the rise of political extremes are the most likely to want to see that expert engagement.

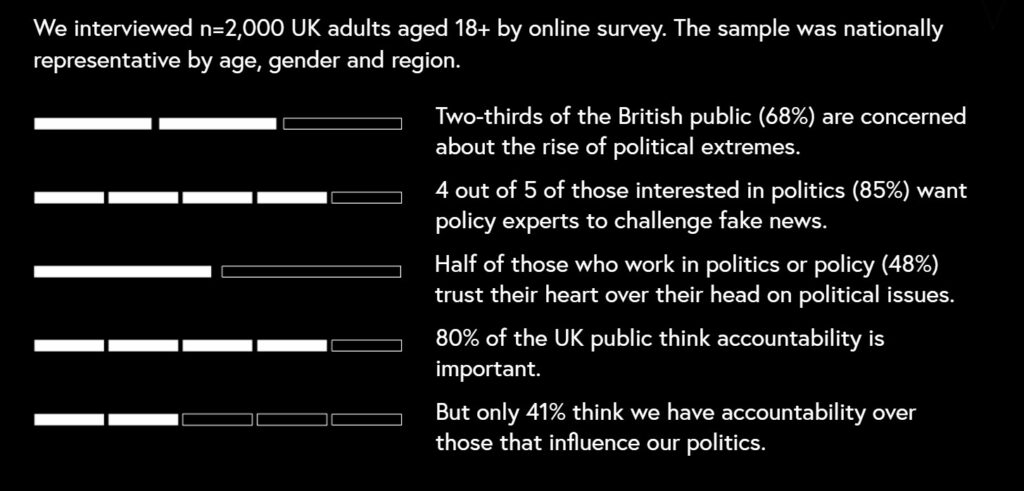

Our reasearch shows that two-thirds of the UK public are concerned about the rise of political extremes. This is true across all segments of the population, but most pronounced among the politically interested, those with university degrees, and the retired.

Crucially, these same segments are also those most likely to want policy experts to challenge news stories that are not true. Over six-in-ten of the UK population want experts to challenge fake news, rising to over eight-in-ten among those interested in politics.

Beyond standing up to fake news, respondents want policy experts to engage with them.

Half of the UK public wants experts to help them understand current affairs issues – again higher among people interested in politics.

The demand exists. The question is, how do we make it constructive and meaningful?

The limits of self-reflection

If we truly want to encourage an informed public debate, we need to recognise the UK public as they are. Warts and all.

The reality is that we, the public, are not good at recognising our own shortcomings.

Last year, Cast From Clay’s research explored if the UK public thought people needed to understand government policy better. Just under three-in-four agreed. This year, we tested whether they were including themselves in this assessment.

Only one-in-four said they did not have a good understanding of government policy. In other words, we’re very good at pointing the finger at other people, less good at pointing it at ourselves.

Bobby Duffy’s Perils of Perception research sheds light on this phenomenon. He found that when challenged about immigration statistics, many respondents simply rejected the official figures if they didn’t fit their world view.

Those familiar with cognitive science will not be surprised.

If policy experts are to help the public understand current affairs and encourage an informed public debate, we need to recognise the power of perception.

Cognitive gaps cannot be addressed by simply presenting facts. We need to frame the issues.

The limits of reason

We need to reconsider the premise of our communications: the notion of the rational citizen who ingests complex arguments and formulates political opinions accordingly.

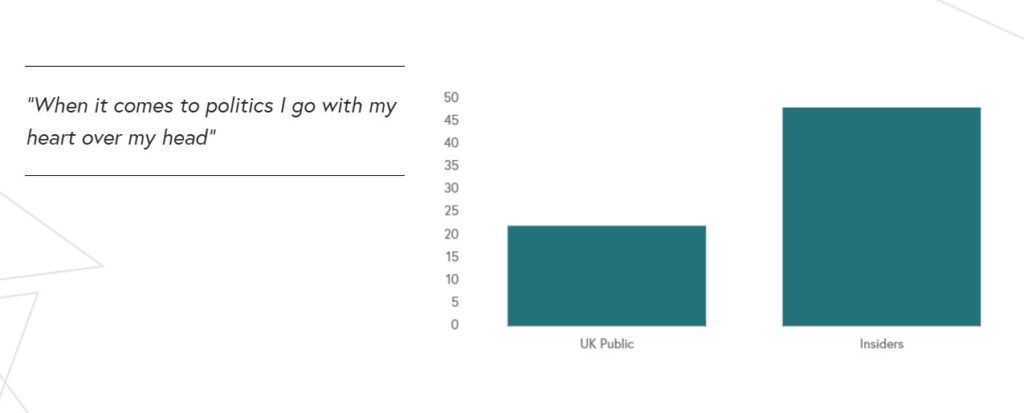

Tellingly, this is not just true of the general public. We found that the closer respondents were to the heart of politics, the more they reported that emotion played a role in shaping their political views.

What may seem at first to be a surprising admission of emotional honesty by political and policy professionals, may simply be evidence of heightened self-awareness. The public are almost certainly as prone to emotion as those who work in politics or policy.

In communicating policy, think tanks need to recognise the limits of the traditional approach – ie presenting facts and statistics, hoping they will speak for themselves.

In highlighting these limits, we are not making the case for bleeding-heart communications. We are simply making a pragmatic case for the need for the human to find a place in policy communications.

There is no other way to counter the populist monopoly on feeling.

“In politics, when reason and emotion collide, emotion invariably wins.”

Drew Westen

The accountability gap

The need to engage is about more than a sense of moral duty. It should also be about a sense of self-preservation for those who seek to influence policy.

Last year, we explored questions around trust in think tanks. Only a quarter of people interested in politics reported trusting what think tanks have to say, and four-in-ten believed think tanks had the interests of the elite at heart. In other words, the state of play isn’t great.

This year we explored the question of accountability over policy influence. We recognise that not all think tanks see themselves as influencers of policy. But when it comes to public trust, it is perception that counts.

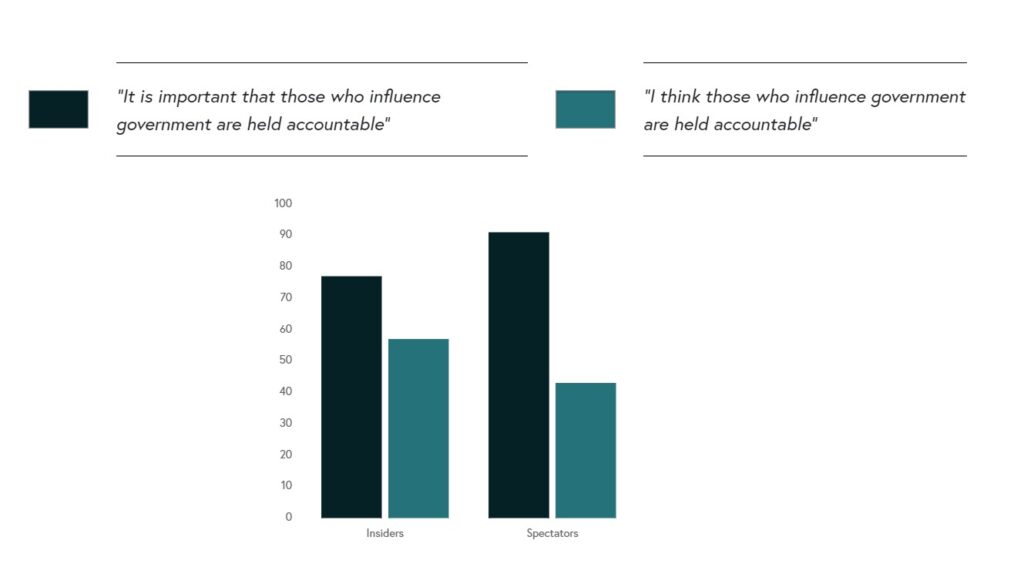

While eight-in-ten Brits think organisations who influence government need to be accountable, only four-in-ten think accountability is a reality. A 39-point gap. Among those interested in politics, the gap rises to 48 points.

A different story emerges for those who work in politics and policy. They are both less likely to place importance on accountability, and they are much more likely to say that political influencers are already being held accountable.

This gap in perception should be food for thought for those involved in influencing policy, whose business it is to engage with policy makers. The public outcry against the Institute for Economic Affairs, and the recurrent “Who funds you?” requests, shows think tanks increasingly under scrutiny.

Society does not write a blank cheque. Organisations need to earn the right to do what they do: they need a metaphorical licence to operate. Especially when it comes to influencing power.

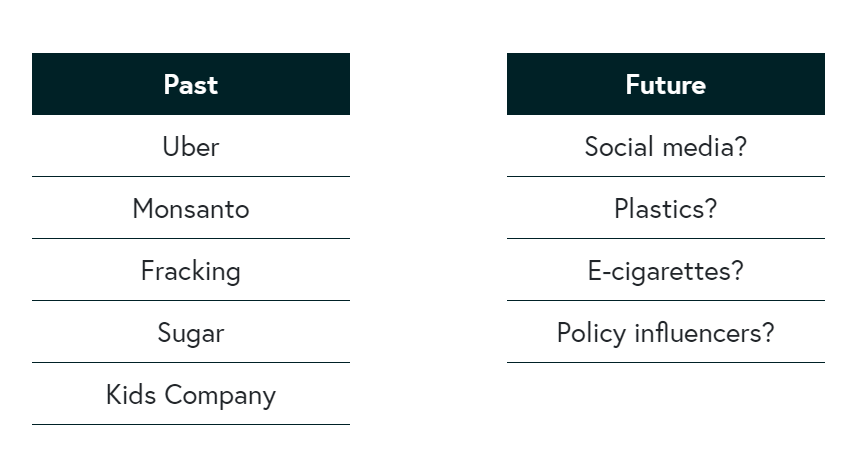

Examples abound in the corporate world where companies and industries did not maintain their licence to operate. Uber quite literally lost their licence to operate in London, forcing it to make changes to its practices to be reapproved. The sugar industry has been fighting a perception war for some years now, and lost a significant battle with the introduction of a sugar tax. And fracking as an industry has never had it easy.

Today we see plastics, e-cigarettes, and social media companies facing challenges to their operating models. It is not clear whether policy influencers are at crisis point yet, but the warnings lights are starting to flash.

Think tanks’ position as idea generators is not a given

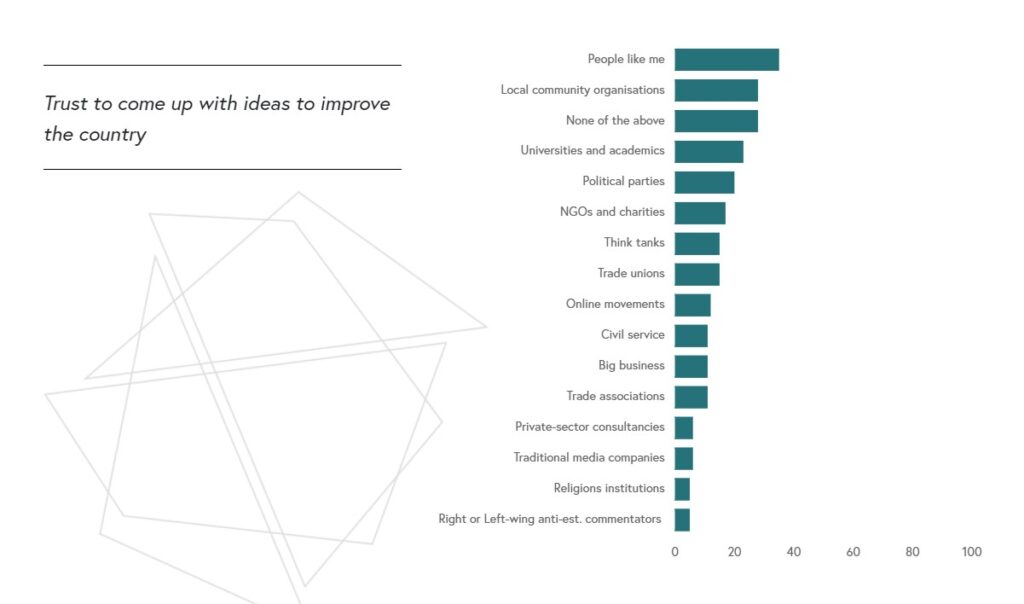

There is no single unanimously trusted source of policy ideas across any of the groups we tested. That much is clear.

Among the UK public, think tanks come some way below local community organisations and academia as trusted sources of policy ideas. And think tanks are neck-and-neck with the trade unions, NGOs and charities, and online movements.

Perhaps most worrying for think tanks is that people who work in politics or policy are only marginally more likely to trust them to come up with ideas to improve the country than the civil service. The business of ideas is close to being trumped by the very organisation it is intended to support.

The lack of trust in institutions to come up with ideas to improve the country has left the field wide open. And in that space “people like me” dominate. In every segment, this populist feeling is mimicked.

Among insiders – those that work in politics and policy – the story is no different. No-one is seen as coming up with ideas for a better Britain.

Policy experts as conversation starters

Our findings on how people like to receive political or policy ideas opens an interesting twist on what engagement could come to mean.

This year’s research explored the formats which people engage with most, in the context of political or policy ideas. Out of the twenty formats tested – which included PDF reports, events, mainstream news, social media and infographics – the top five were perhaps unsurprising.

Mainstream news retained a place at the top table, though there was a marked difference between online and print – the latter on a downward trend, the former more stable. Documentaries were also a popular format. Most notable, however, was the prominence of peer conversation and social media. And the clear preference for social media among younger audiences foreshadowed what policy communication may look like in 5-10 years time.

The question is this: in a world where people prefer talking things through with people they trust, is there an opportunity for a rethink of what engagement means?

Rather than playing a paternalistic role of bestowing knowledge on the public, could think tanks could have more of a role as convenors? Generating ideas, framing the debate, and then orchestrating an informed public dialogue. The public wants policy experts to speak out and engage. But they need to speak in terms which will resonate with humans – public and policy makers alike – with all their foibles.

Yes, policy experts will win the intellectual argument all day long, based on their vast bank of facts and statistics. But if their facts challenge an individual’s pre-existing frames – be they policy maker or public – the facts will be dismissed almost every time.

This tension lies at the heart of the frustration which is driving populism – a gut-feel that the facts and statistics are not reflecting people’s own lived experience.

If Watford is anything to go by, the human experience needs to have a voice.

1. The public matter as a policy audience – and they expect policy experts to be more proactive

What role is there for think tanks?

2. If we want to improve public debate, we need to look beyond fact-based communications alone

How can think tanks tap into the human?

3. We need to maintain policy influencers’ licence to operate

What are the risks for think tanks?

We’ve presented the full findings to communicators and researchers at policy organisations like IPPR, Centre for Policy Studies, RUSI, and the Institute for Government. Get in touch with Tom Hashemi if you’d like to arrange a complimentary presentation of the full results.

We would like to thank the many individuals who have supported us – including challenging our thinking – over the past few years. Special mentions to Andrew Marshall, Benedict McAleenan, Clara Widdison, David Wastell, Emily Duncan, Enrique Mendizabal, Helen Dempster, Joe Miller, John Schwartz, Joseph Barnsley, Katy Murray, Laura McDonald, and Madeleine Burns. Credits to Katie and Andy for the design of this site, Vitaliy for build, and Tim for keeping us all in line.