Credible but not effective communicators

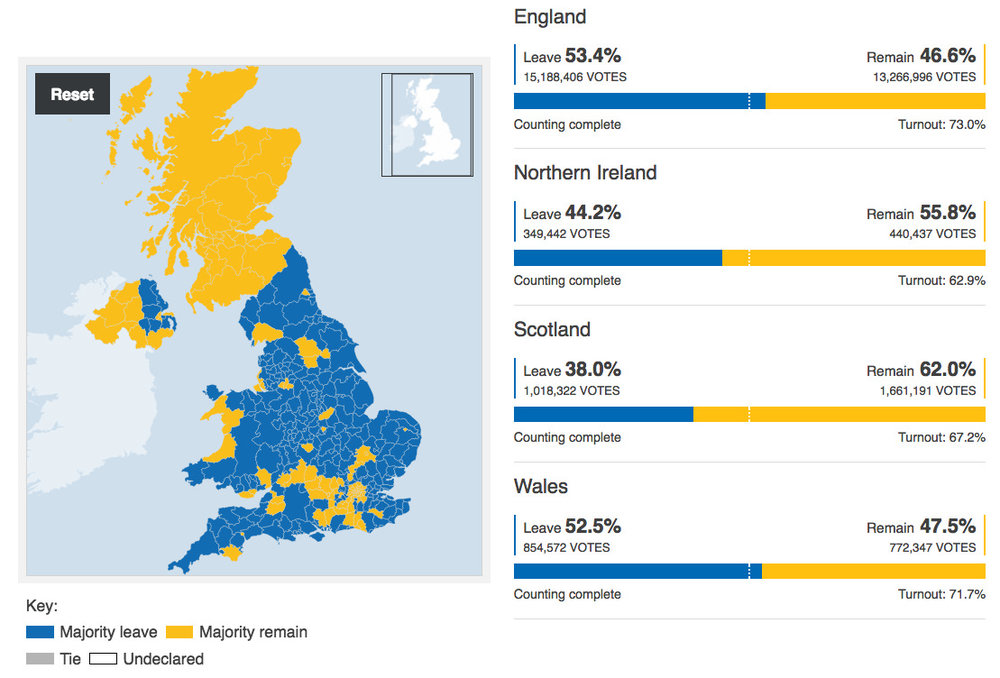

Technical expertise and fact-based policy were brushed aside in favour of an approach which put emotion and gut-feel on an equal footing with evidence and statistics.

This is both powerful and dangerous. It signalled to voters that regardless of whether the figures back you up, you have a right to feel the way you do.

In the UK, warnings from economic, academic, and environmental experts, not to mention business leaders and politicians, were all ignored. In the US, efforts like #NeverTrump and the letter by GOP national security officials fell on deaf ears. Expertise was toxic.

In this context it is perhaps surprising to see that experts are still the most credible spokespeople. Our former agency Edelman released the 2018 Trust Barometer recently, showing that technical experts are seen as credible by 62% of Brits, with academic credibility at 61% (sitting well ahead of government at 37% and journalists at 32%).

How do we make sense of the fact that the public sees experts as credible spokespeople, while simultaneously dismissing their advice?

Think tanks adrift

Think tanks play an essential role in generating policy ideas. But without effective public engagement around those ideas the risk is that they have no real-world impact.

Are we, as Tom Nichols puts it, witnessing the death of the ideal of expertise? Or is this a case of experts failing to navigate today’s hyper-connected world, of experts not knowing how to communicate their expertise?

“I fear we are witnessing the death of the ideal of expertise itself”

Tom Nichols

credit Politico

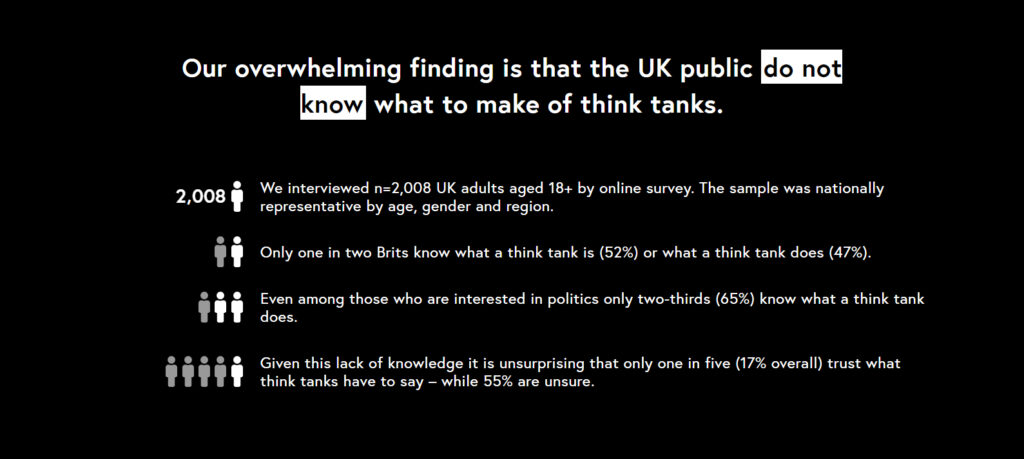

We conducted this research to see what Brits think of one specific breed of expert and how they communicate: think tanks. Do they know what think tanks are? Do they trust what they say? Do Brits actually want to understand government policy better? And if so, how?

The Ivory Tower

There’s a significant disconnect between the views of those who work in the realm of politics, policy or government (“Insiders” – 10% of our sample) and those who are simply interested in politics (“Spectators” – 53% of our sample).

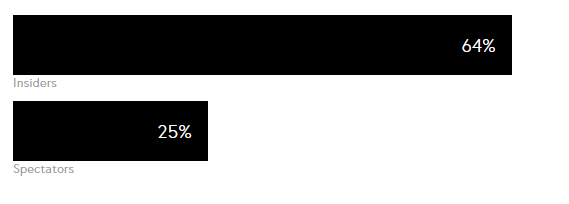

As can be expected, a majority of Insiders trust what think tanks have to say (64%). This is not the case with Spectators, of whom half (50%) don’t know whether to trust what think tanks say and a quarter (25%) openly distrust them.

TRUST IN WHAT THINK TANKS HAVE TO SAY

While two-thirds of Insiders (63%) believe think tanks do positive work, less than a third of Spectators (31%) believe this to be true. Again half (53%) of Spectators – people who are interested in politics – simply don’t know whether think tanks do positive work or not.

INSIDERS BELIEVE THINK TANKS REPRESENT THE INTERESTS OF THE ELITE

Most surprising is the view among Insiders that think tanks represent the interests of the elite, nearly seven in ten (68%) of whom agreed.

What is clear is that a substantial number of Brits wish to see full think tank financial transparency (72% of those who know what a think tank is).

Communications tanks

While Insiders and Spectators may not share the same views of think tanks, they are aligned when it comes to one thing: the general population needs to understand government policy better. Around eight in ten of both Insiders (74%) and Spectators (86%) agree.

This is consistent across the urban/rural divide, every income level and every age group. Over half of respondents in each of those constituencies felt that the public needed to understand government policy better.

THE POLITICAL DIVIDE IN 2016

But less than one in five (16%) believe government policy is currently communicated well, a finding that was also consistent across the main regions of the country.

Insiders, however, disagreed: nearly six in ten (57%) of whom think that policy communications are done well.

Our findings show a gap between public demand for, and supply of, good policy communication.

Think tanks can play a key role – however, they need to earn the public’s trust first.

The good news is that while few people trust think tanks, the majority don’t know what to make of them. Think tanks need to educate the public about what they do, and the positive role they can play in sound, evidence-based policy making.

But they need to go much further than they currently do – they need to engage hearts as well as minds. Failure to do so could signal the downfall of an important democratic institution – and in this hyper-connected world, its replacement with something far worse.