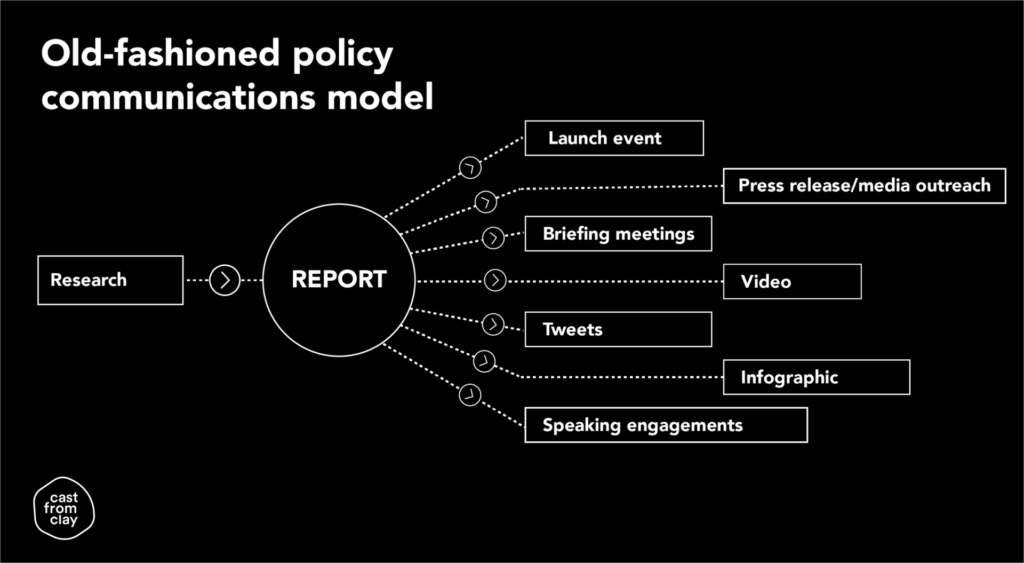

It is an area we have been looking into for a while. A discussion born out of frustration with (and boredom of) the old-school way of communicating policy. Namely:

Expert or academic carries out research. Generates rigorous 40-page report. Comms officer is asked to promote said report. Launch event, press release, tweets. Maybe a video. Maybe an infographic.

The only problem is that this model doesn’t work. This is the first of a two-part blog focusing on a new model for policy communications.

A tired communications model

The old model puts the report at the centre of the campaign. The messages are drawn from the report, and the other communication assets are then, almost by definition, subservient to the report.

The challenge is that for the researcher, the report is the hub – the culmination of often months of research. For the comms specialist, however, it is just one of a number of comms assets. And the messages themselves supersede every one of them.

This traditional model is a 2-dimensional comms approach for a 3-dimensional world.

Reports barely work as a format

This is not a matter of taste. A scan of the latest reports of the top 20 think tanks in the UK and the US shows that reports are 42.5 pages on average. (There is only a marginal difference between the UK and the US on this.)

Here at Cast From Clay we firmly believe policy experts like think tanks need to engage not just policymakers, but also the wider public, or risk becoming irrelevant. And the wider public doesn’t read 42.5-page reports.

More to the point, neither do policymakers. In 2014, a survey of all White House officials involved in national security under both George Bushes and Bill Clinton found that policy researchers were not providing what policymakers need, and as a result their influence on actual policy was limited.

One respondent observed that research papers that exceed 10-15 pages are simply not useful to policymakers. Another respondent noted that “I do not have the time to read much so cannot cite” many examples of useful social science scholarship.

While the survey focused on national security policymakers and their relationship with academia, we have no reason to believe these findings do not apply across sectors. And there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that they do.

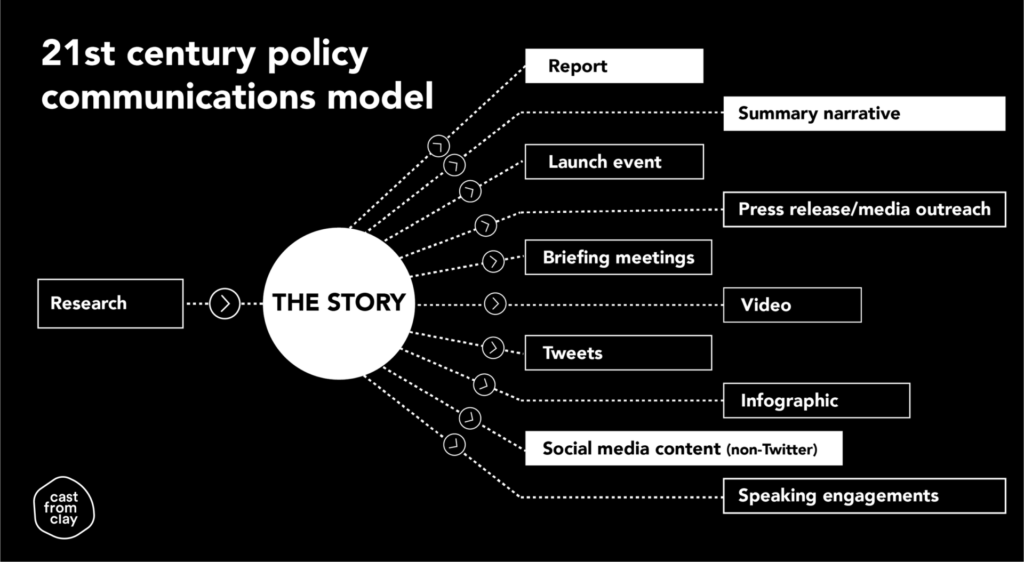

A communications model for the 21st century

We believe a reframing is required – and so do many of the policy communications specialists we speak to. The main barrier that is mentioned is typically a lack of time to plot an alternative route. In those instances, the beaten path always wins.

So here is an alternative model which seeks to break the equivalence between the report and the messaging. This model is the very one which has been mastered by the alt-right. While it might seem self-evident, it is not the norm among think tanks.

One of the key findings from the survey was that senior officials want a framework to help them understand the complexities of the world. The respondents expressed a preference for scholars “to produce ‘arguments’ (what we would call theories) over the generation of specific ‘evidence’ (what we think of as facts)”.

In other words, policymakers want policy researchers to provide them with a narrative: a ‘story’. And in the context of politics, the best story – not the best facts – wins. This has always been the case, but it has never been truer than today.

With this model, we hope policy communications professionals can provide an alternative to the old-fashioned model. Some, like Heritage in the US, are already doing this. We’d love to see more.

In the second part of this blog series, we will look at how various comms assets can help tell a rich story and guide policymakers along the journey to policy adoption.

Read part 2 here