Some months ago I sat in a friend’s living room sifting through her books and noticed a battered large book on the top shelf. It was her great great grandmother’s childhood scrapbook from the mid-1800s. Alongside the glued in cut-outs of dolls, animals and landscape scenes was a page of military decorations from the Victoria Cross to the Baltic Medal.

It reminded me of the football stickers I collected as a kid. It is strange to think that that these decorations were as culturally dominant as football and Euro 96 were in my childhood. What is clear is that perceptions of Armed Forces, and the esteem they are held in, have changed significantly.

This article presents findings from primary research conducted by Cast From Clay. The core argument is that stories are an effective way of changing perceptions and that policy actors need to move away from an over-reliance on data and statistics to do the hard work of changing attitudes. Stories can be used to better communicate the purpose of defence and to bolster public support for the Armed Forces.

Modern Context

Today, national security sits low on the agenda for many people. Those born after the Cold War, including most ‘millennials’ and ‘Gen Z’, have little experience or personal connection with conflict to draw on. Many don’t appreciate the delicate balance between peace and international relations, Britain’s place within it, and whether defence and security are even relevant issues at all.

From a polling perspective, this perception can be seen in YouGov data from the run up to the UK’s 2019 general election where defence and national security came 10th in a ranking of the public’s election priorities.

These trends have contributed to a growing funding crisis for Britain’s Armed Forces, alongside challenges in recruitment and retention. The implications of this could be serious for security both within our borders and for Britain’s wider strategic role on the world stage. As the Government pursues a strategy of #GlobalBritain, the Armed Forces are likely to be significant stakeholders in achieving this vision; but only if the public understand and support it.

Changing Perceptions

Against this backdrop, what can be done to encourage people to see the military as relevant today; both as an organisation that positively impacts lives and something that people might want to be part of?

The British Army is acutely aware of the value of public engagement.

“Work to define the Army Brand in 2017 focused on developing a lexicon and a tone – a house style – that would resonate with the audiences we wanted to engage. Since then, we have focused on telling stories about the Army, its purpose and ethos, that aim to enhance our reputation.

In the UK, we particularly concentrate on illustrating why society should value and be proud of their Army and the ways it protects the nation. Public favourability is important for many reasons, but high among them is our desire for great people to serve with us.”

— Major General Neil Sexton, Director of Engagement and Communications, the British Army

The Army’s approach shows an appreciation of how careful framing of stories can shape people’s views. In other words, story telling demonstrates the contemporary relevance of the military institution in convincing people to consider it as a career.

Hiding Behind Words and Numbers

Despite the power of storytelling being well understood, the British Army are an outlier.

The power of narrative is often overlooked in policy spaces by actors who attempt to shape perceptions using facts and data. They often also use language that is impenetrable to outsiders.

If you examine the Twitter feeds of leading think tanks, for example, you will find streams of references to billion-pound sums and statistics, not to mention the endless acronyms. Of course, this starts with their names: RUSI, IPPR, CPS, IEA, CSJ, IISS… and so on.

The military and broader defence community are equally guilty of this.

Language can often be used as a means of limiting conversation to those already in ‘the gang’ rather than opening it up and allowing broader engagement. When I spoke at the CHACR annual conference in Camberley last year there were several points where I did not understand my fellow speakers (including references to the SDSR – why not “2020 Defence Strategy”?). Despite having an MA in War Studies, I lacked the institutional vocabulary needed to decipher what I was hearing.

This is not unique to the military: almost every institution or grouping of experts does this. But if the goal is to engage new audiences, whether they be the public or policymakers, this is not a useful approach. Think of the best medical doctors. They help you understand what is wrong without using the technical language they would with their peers. It is the sign of someone who truly knows their craft.

Language aside, policy actors’ reliance on data to effect attitudinal change is unfounded. Time and time again, the evidence has shown that stories are much more effective in changing opinions.

I am not making an argument that research does not matter. Quite the contrary. Cast From Clay exists because of a belief that research and evidence do matter. But it is a recognition that research and data are rarely effective communications tools. They are the foundation for the communication, not how we execute it.

Power of the Narrative

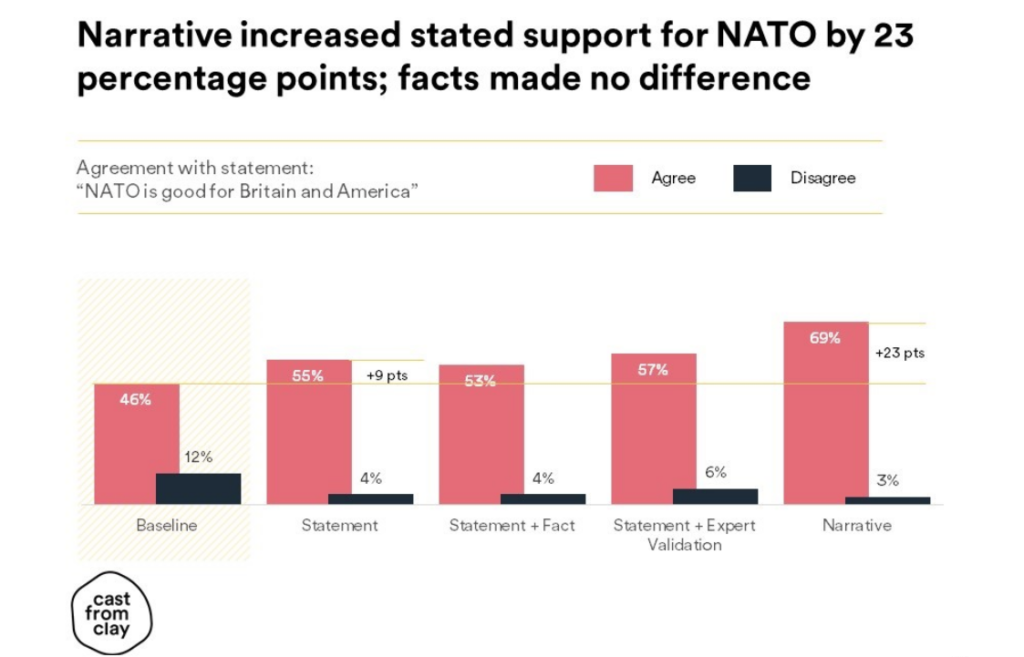

To see if stories are as powerful in changing perceptions in the national security space as people say they are, Cast From Clay designed a study among the UK public. To capture data we commissioned an online survey among a nationally representative sample of 1,000 adults aged 18+ to see if we could influence their views towards NATO with just one sentence.

First, the baseline. Without any meddling from us, we found UK support for NATO at 46%. This is a similar figure to previous studies, including one in 2019 from Pew.

We then tried to alter this level of support in four ways. In the survey we split respondents randomly into four groups and gave each a statement on the positive value of NATO. We asked if they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

The first was a statement with no supporting evidence (simply “NATO is good for Britain and America”), the second was the same statement supported by a statistic, the third the same statement but this time supported by a quote from an expert, and finally the same statement woven into a narrative.

- Statement alone

- Statement + statistic

- Statement + expert quote

- Statement woven into a narrative

With the plain statement alone, option 1, we found an increase in stated support of nine percentage points. In other words, just telling people NATO is good has an uplifting effect.

The second and third options (statistic + expert quote) had no further impact. This provides additional proof that relying on data to change opinions rarely works.

As for the narrative, a single sentence expounding the purpose and impact of NATO drove support up 23 percentage points. This clearly shows the power of narrative story telling in communicating defence messages.

So What?

These conclusions reinforce that stories are appealing to people and can be used to effectively change perceptions. People are eager for stories to help them understand the world and storytelling in turn helps underline the importance and relevance of public defence and national security.

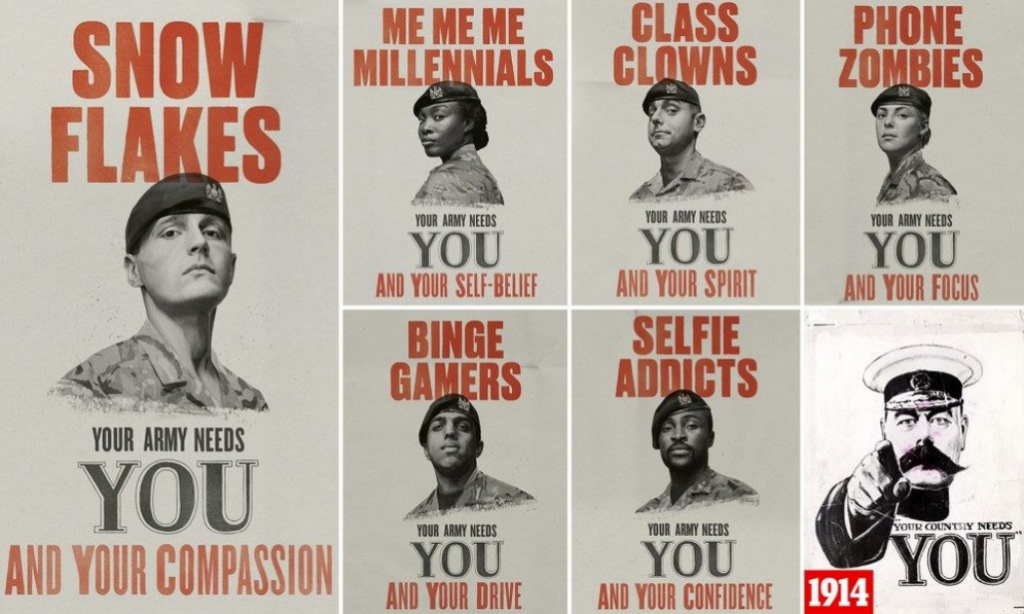

This can be seen through the results of the British Army’s recent recruiting campaign. While the campaign received criticism on social media, it met its recruit applications target ahead of schedule and ended up as the Army’s most successful campaign in a decade. The goal of a communications campaign is to appeal to its target audiences and achieve a business objective. It is not to win “most liked campaign among the Twitterati”.

In the same way that this storytelling approach has worked for military recruitment, it could be better used to win policymakers’ support for military matters, too.

People Respond to Human Influences

Policymakers are people like the rest of us. We often ascribe them special status, but they are influenced in much the same way. They want arguments and narratives to inform them; they do not always want yet more data presented to them in 80-page reports.

This support from decision makers is crucial in ensuring that the Armed Forces and intelligence services receive sufficient funding to maintain their global leadership.

Critically, public spending on national security should not be perceived as narcissistic or a glorification of state combat. Quite the opposite: appropriate resourcing is essential to prevent future conflict. Telling a coherent story that resonates with the audiences that have a stake in this debate is an important tactic in ring fencing such funding.

Perhaps counterintuitively, then, the best way to prevent a return to a world where the Armed Forces are the focus of young children’s sticker books is by embedding a narrative around the relevance of national security into the national discourse. By capturing the public and political imagination in such a way, we will be better placed to ensure our national security through intelligence and conflict prevention than by working things out with war.