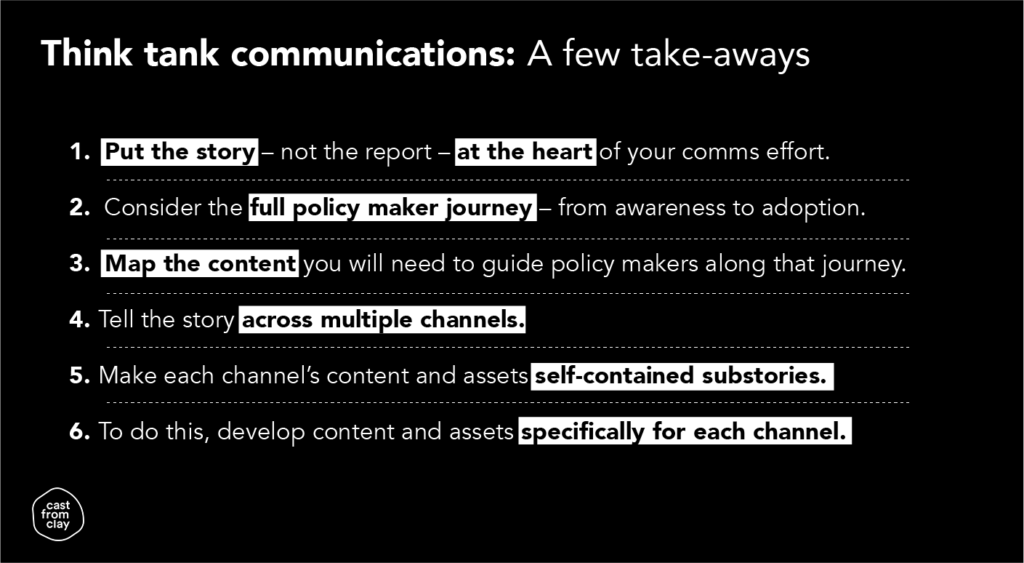

In my last post, I argued that a reframing of policy communications was required – away from the report, and towards ‘the story’. This post looks at how your communication content, assets and activity bring your story to life, which in turn helps you achieve your objectives.

The objective here has to be the adoption of your policy, recommendations, or narrative. While the key deliverable for you as a research institute or think tank may be a report, for your funders the report is usually just an output. Ultimately, they want to see your work have an impact.

Taking policymakers on a journey

We all know that policymakers are time-poor – at any one time, your policy or recommendations are vying for their attention not just with other policies, but broader government or internal party affairs, campaigns, constituency or even family issues. We have to earn their time.

Crucially, getting policymakers’ attention is only half the battle. Awareness is the first step, but ultimately success will be measured in terms of policymakers’ actions. However, too often this is where communications activity falls short.

The policymaker survey mentioned in the last post clearly signalled that policymakers are not likely to invest the time required to read a 40-page report until they have bought into the story that you are trying to sell to them.

To be clear, we are not saying that reports have no role. But traditionally, we have tried to push the report before having even earned policymakers’ time. What we are saying is that the report is only useful as a communications asset near the end of the journey.

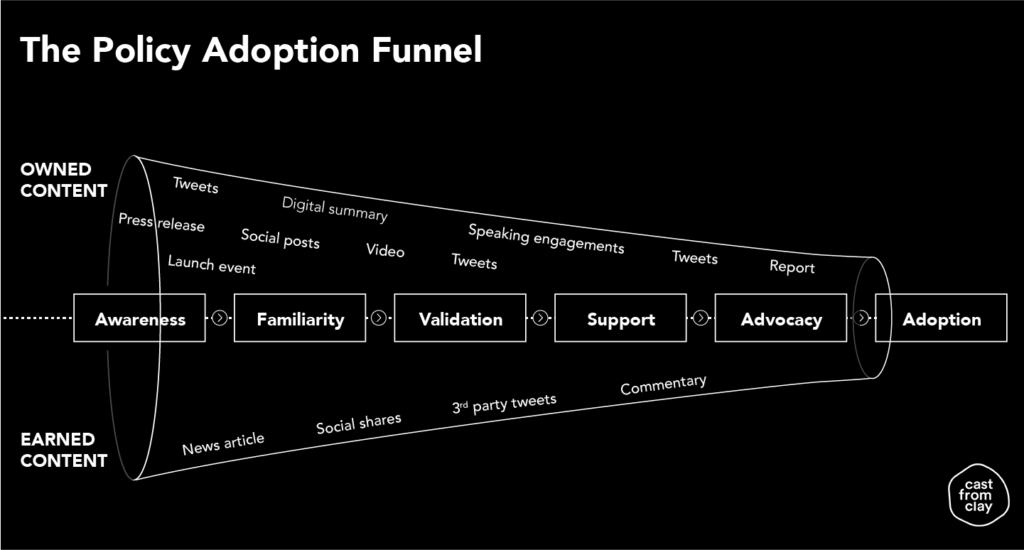

Learning from sales: the Policy Adoption Funnel

To illustrate this, we can take inspiration from marketers, among whom the respective merits of short-form and long-form content are well understood. Sales people talk about the ‘purchase funnel’, which is a model journey used to turn consumers into buyers.

Typically, at the start of the funnel – often before the consumer has even decided to buy anything – short-form content is most effective. The short-form content is useful to give an overview of the product or service, or to introduce the company.

Long-form content, however, is more useful once the consumer has decided to buy, and has narrowed down their options. The long-form content is used to provide a detailed specification of the product or service, or even case studies, which potential buyers can use to compare with competitors’ and make an informed decision.

How do we relate this to policy communications? Experts need to guide policymakers along a journey that takes them from not having heard of their work to championing it, through the judicious use of content and communications assets.

In this scenario, tweets, social media posts, short overview videos and news coverage guide policymakers along the journey from awareness to familiarity. By their nature, these are typically short/medium-length content.

Invitations to speak, endorsements by commentators and social media shares by influencers provide social validation, which we know to be a key driver of opinion-forming, and will (hopefully) start generating interest and support.

Finally, once the policymaker is primed to externalise their support, detailed expert commentary – and the report itself – can help turn them into vocal advocates, safe in the knowledge that they have done their due diligence. Hitting them with the report at the start of their journey is like taking a hammer to a screw.

Telling a story through short or medium-length content

The policymaker survey provides confirmation – it contends that the popularity of news articles and op/eds among policymakers is due as much to their short length as to the influence of the news outlets.

Like us, they are not suggesting that short/medium-length content should entirely replace long-form. Rather, they “strongly believe that research findings which cannot be presented in that format are unlikely to shape policy”.

This conclusion is consistent with the anecdotal feedback we have been given over the years. In that regard, we have experimented with a few formats ourselves: video summaries, infographics, blog posts, digitised reports, etc.

For what it’s worth, we like the ‘digital summary’ format. It strikes the right balance between all our audience’s needs – storytelling, manageable length while providing sufficient detail, engagement and ‘shareability’.

We used this format ourselves for our recent research on trust in think tanks: Forging the Think Tank Narrative (UK and US).

Transmedia storytelling: content mapped across the user journey

Of course, the digital summary is just one method of delivering the story – though to us it is one of the most important ones. The story needs to live across multiple channels, through self-contained content developed specifically for each particular channel.

On that subject, the best explanation we have read is Joe Miller’s blog post explaining transmedia storytelling in terms of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. We can’t improve on it, so here is the link: ‘WonkComms and the Marvel Cinematic Universe’.

Joe sets out the difference between the current ‘Paratext model’, where all the communications content and assets are accessories to the report itself (think of movies vs trailers/posters). And the ‘Transmedia model’, where they are substories in themselves – self-contained, but intrinsic to telling the broader story (hence the Marvel Cinematic Universe analogy).

Yes the Transmedia model might take a little more effort, though not as much as you think, and only initially. But the fundamental problem with the ‘Paratext model’ is this: what happens to the overall message of your story, if people see the trailer or the merchandise, but no one watches the actual movie?

Transmedia storytelling is the perfect vehicle to drive the Policy Adoption Funnel. As communications professionals, we simply must do better.

If you need help implementing this in your organisation, we can help. Get in touch.