The name is generally the most recognisable identifier for an organisation. And yet, from that point of view, the think tank sector is quite unique in that the name is often the least unique part of the brand. (This is the thinking behind our Name My Think Tank name generator!)

When Michael Gove rebuked “experts with organisations with acronyms” in 2016, it hurt because there was a kernel of truth in that depiction. He was making a point about how interchangeable these expert policy organisations appeared. Nameless. Faceless.

The importance of naming a think tank has come up in two projects recently, and in many more over the years. So we’ve been reflecting on this, and learned some useful lessons on the matter over that period – here are our main take-aways.

Types of names

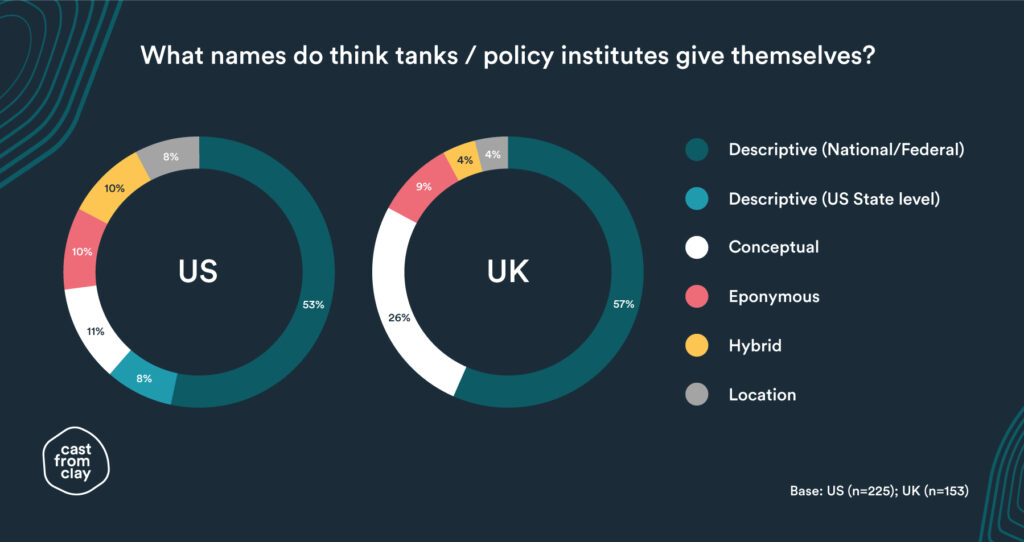

Think tank names typically fall into a number of predictable categories. Below, we’ve mapped the name of the 225 US think tanks and 153 UK think tanks listed on Wikipedia (as at 24 Jan 2021).

Descriptive

This is by some distance the most common naming convention, in both the US and the UK. The name is used to describe what the organisation majors on – whether in terms of topic, or in terms of the geography/culture it focuses on. This naming approach is particularly popular among the more academic think tanks, though not exclusively.

A sub-division of this category occurs in the US, where the same naming convention is applied, alongside a State- or city-level qualifier.

Examples:

- Council on Foreign Relations

- Center for Global Development

- Middle East Institute

- National Institute of Economic and Social Research

- Institute for Public Policy Research

- Oregon Center for Public Policy

- Public Policy Institute of California

Conceptual

The name is used to describe a foundational concept, which gives us an idea of what the think tank or policy organisation is interested in, and the angle they are coming from or the vision they are working towards.

The concepts include both modern formulations, and classic. The conceptual approach is particularly popular in the UK, though it is also well represented in the US. And it is just as prevalent across the political spectrum.

Examples:

- Heritage Foundation

- New America

- Seven Pillars Institute

- Demos

- Onward

- Bright Blue

- ResPublica

Eponymous

The organisation is named after a public figure. The individual is sometimes the founder, but it can just as easily be a figure from history – recent (Adam Smith) or ancient (Cato) – or even a contemporary thinker (Ludwig von Mises).

Either way, the eponymous figure subliminally gives us an indication of the values that guide the organisation.

Examples:

- Mises Institute

- Cato Institute

- Brookings Institution

- Stimson Center

- Adam Smith Institute

- Nuffield Trust

- Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Location

A number of think tanks have a location-based name. The location can be a number of things. For example, it can be a nod to the university that hosts them, a nearby landmark, or simply the place where the institution was founded.

While location-based names are typically neutral, some have incorporated the names of historically-significant locations – for instance the Bruges Group is named after the location of a speech delivered by Margaret Thatcher about Europe. In these cases, the location provides an indication of the organisation’s political values.

Examples:

- Ripon Society

- Jamestown Foundation

- Claremont Institute

- 38 North

- J Street

- Bruges Group

- Oxford Research Group

- Selsdon Group

Hybrid

A number of organisations use a hybrid approach drawing on two of the above categories. The most common combination is either ‘Eponymous + Descriptive’ or ‘Location + Descriptive’ – and occasionally ‘Eponymous + Conceptual’, though this is far rarer.

Examples:

- Belfer Center for Science & International Affairs

- Washington Institute for Near East Policy

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Manchester Institute of Innovation Research

- LSE Ideas

- Halsbury’s Law Exchange

‘Organisations with acronyms’

The charts above show that the most common approach, by some distance, is the descriptive approach. This seems to be the default, especially towards the more academic end of the spectrum.

It is a perfectly valid naming approach for an academic policy institute. However, if you are founding a new think tank which aspires to influence real-world policy, it is worth reflecting on the implications of the Gove quote.

“I think the people in this country have had enough of experts with organisations with acronyms saying that they know what is best and getting it consistently wrong.”

As mentioned prior, there is an uncomfortable truth underlying this statement: in a crowded policy space, there is little to tell one think tank from another – even when you work in the sector. (Check out our Name My Think Tank name generator.)

This is mainly because the majority of think tanks have done very little work to build their brands, to establish a unique positioning, to develop a brand narrative. If your brand name is interchangeable, this is always going to be hard!

We can take heart, however, from the fact that a few think tanks have managed to rise above the alphabet soup by building their brand.

One example is the Royal Institute of International Affairs, which has come to be known as Chatham House. Its brand has been served well by a willingness to tell the Chatham House story (and certainly not hindered by the ubiquity of the ‘Chatham House rule’).

Another example is the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts rebranded itself as Nesta, and repositioned itself as a research-led innovation think tank, with a brand narrative and visual identity to match.

There are others. This is not about size, or money. What all of these think tanks have in common is a commitment to brand-building.

How to name your think tank

Let’s start with a few questions:

- Do you want your organisation to influence policy?

- Do you want your organisation to be memorable?

- Do you want your organisation to be uniquely positioned?

- Do you want your organisation to stand for a set of values?

If the answer to any of these is yes, our recommendation is to stay away from descriptive names. The temptation is to think that this naming approach will ensure your audience knows what kind of organisation you are and what you do. Leave that for your About page.

The truth is that while that may be true, a descriptive name will not only make it incredibly hard to rise above the alphabet soup – it will also de facto position you as part of the faceless policy blob.

Location-based names can be a good option – especially if it is a place of historical significance. But only provided you are willing to proactively tell the story of your organisation. You will need to inject meaning into the name.

However, from a brand point of view, eponymous names or conceptual names will give you a head start. They will provide meaning to your brand from the start, and make it easier to build a recognisable brand in the long run.

And if there is no way to avoid the descriptive name: go for a hybrid name, and keep it punchy!

Final thoughts on eponymous names

An eponymous name can be a powerful way of communicating something about your brand, especially if you are thinking of a historical figure. Picking the right individual can be tricky. Here are 5 questions to guide this process.

1. To what extent did the proposed individual embody your values?

The question here is about vision, beliefs, principles. Due diligence is required – including consideration of the individual’s entire career, and of their private life.

2. To what extent does the proposed individual reflect your mission?

The question here is one of relevance. Is there a clear link between the individual, and your work – e.g. your field of study, expertise, and the nature of the work you do.

3. To what extent does the proposed individual reflect your brand personality?

The question here is one of coherence. For example, are you looking to project gravitas and authority? Or modernity and disruption? The individual needs to reflect these personality traits.

4. Has the proposed individual already lent their name?

The question here is one of clarity. Public figures are popular for a reason, and many organisations want to be associated with them. Is this name already being used?

5. Have you made contact with the proposed individual’s estate?

The question here is one of compatibility. Public figures’ image is often protected – e.g. by their families, by a foundation. They may have rules governing any association, or may not want to be associated at all.

Try out the Name My Think Tank name generator