Elections have been called into question, and key democratic institutions – the judiciary, legislature, and media – have found themselves under attack.

Ahead of the Prospect Think Tank Awards, which we are sponsoring, we spoke to some of the shortlisted candidates. We asked them what it’s like to work at a think tank in this new environment, and what a new agenda for policy organisations might look like.

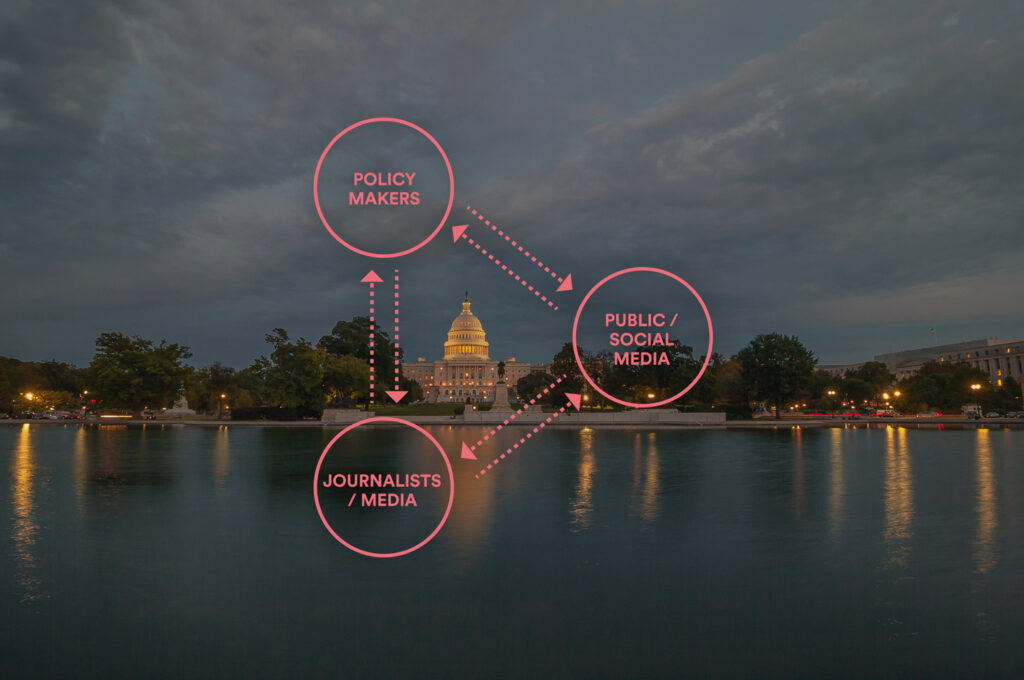

Think tanks face a communications challenge

There’s lots that policy organisations can learn from the media’s recent experience. Journalists’ role in informing the public and shaping public opinion has been shaken. Many citizens now dispute their claim to supply democracies with essential facts and data.

This has implications for how think tanks influence the public conversation. Saqeb Mueen was until very recently the Director of Communications for the UK’s Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), which is the UK’s oldest defence and security think tank.

“Traditionally, think tanks have been a go-to source for ideas, authority and scrutiny,” Saqeb explains. “And good think tank experts, especially after the election of Trump, were still sought after by traditional news media and continue to be today. The problem for think tanks, however, is that if they rely on traditional media, they are focusing on a medium that is itself competing with the fake news that is characterised by the Trump era.”

The problem for think tanks is that if they rely on traditional media, they are focusing on a medium that is itself competing with the fake news that is characterised by the Trump era

Saqeb Mueen, RUSI

The digital era makes everyone a publisher and undermines gatekeepers. Many thinktankers have, in response, expanded their communications functions and built their capacity to reach audiences directly. Iryna Shyba directs Ukraine’s DEJURE Foundation, set up to push for the judicial reforms Ukrainians demanded in the 2013 ‘Revolution of Dignity’.

Newer think tanks like DEJURE have communications and advocacy built in to how they do research. As Iryna says, “20% of our work is about writing research, analysing data, writing reports, writing articles. But the rest of it is actually repacking [these] analytical materials and analytical conclusions to different audiences …”

Reuben Abraham at India’s IDFC Institute agrees. His organisation aims to support India’s transition from a low-income state-led country to a prosperous market-based economy.

Communication must not be an afterthought, but core to strategy at a research organisation

Reuben Abraham, IDFC Institute

“When you formulate research questions, you should also have thought about ‘how am I going to get this out? What’s the strategy’?”, he says. “The usefulness of applied research depends on the ability to communicate it … communication must not be an afterthought, but core to strategy at a research organisation.”

Addressing perceptions of elitism

Established media organisations find themselves distrusted by the populist left and the populist right, and accused of being mouthpieces of the elites. Now, policy organisations have also traditionally claimed to equip democracies with the knowledge they need to make good choices. But like established media, their impartiality has been questioned.

Our own research has found that only 1 in 5 people trust what think tanks have to say. Of those working in politics, 68% believe think tanks represent the interests of the elite.

Only 1 in 5 people trust what think tanks have to say. Of those working in politics, 68% believe think tanks represent the interests of the elite

Cast From Clay research

Saqeb recognises this. “Because we have royal patronage, because of our location in Whitehall – next door to the UK’s government departments – and because of our rich heritage, we are seen as very much part of the establishment. Whereas in fact, we are an independent think tank, non-partisan, critical of the government at times, fostering and welcoming different views and now reflecting a diverse workforce. We challenge that perception through the dissemination of our work and the projection of our people”

In a world of culture wars and ‘alternative facts’, journalists are having to re-examine what principles of objectivity, impartiality, and non-partisanship mean. And some think tanks with traditional positioning – where they just provide a non-partisan evidence base, leaving political questions to someone else – are revising their stance, too.

For Reuben, organisations that see politics as a job that lies elsewhere are “primarily in the business of providing inputs. Then, the policy process takes over from there on. However, if you believe that outputs and outcomes are also something that matter to you, then there is no escaping the political economy. You have to engage in the politics of it. There is just no other way to do it.”

If you believe that outputs and outcomes are also something that matter to you, then there is no escaping the political economy. You have to engage in the politics of it.

Reuben Abraham, IDFC Institute

Victoria Winckler leads the Bevan Foundation, which aims to “end poverty and inequality” in Wales. That means looking at “policy and practice”, including such specific questions as “how people access a particular service”.

The scope of Victoria’s and Reuben’s work is determined not by abstract principles but by what their societies and political systems need. As Victoria says:

We don’t consider the job done if you get a successful policy.

Victoria Winckler, Bevan Foundation

Reuben brings another perspective. “One of the key issues with developing countries is the lack of state capacity. In a constrained environment of state capacity, if you care about outcomes, then it’s like you have no option but to engage in a process that goes from ideation to institutionalisation.”

So for policy organisations, responding to accusations of elitism clearly has implications for communications. It also means some policy organisations are doing new things, like focusing intensely on the implementation of policy and the political questions that raises.

This comes with challenges. Ben Franklin, at the UK’s Centre for Progressive Policy, is a former civil servant. He says that “working in the civil service at Whitehall, there isn’t this kind of arms open, ‘we’re going to talk to everyone who’s essential on this topic’” attitude. In his words, it’s an “insular experience”.

He believes think tanks have a role in opening up policymaking. “If a policy does shift,” says Ben, “it’s not just because one think tank said so …”

For Victoria, this means “that our staff are transferring some of their skills”, running training on decisionmaking, how to make Freedom of Information requests, and how to approach media interviews.

Are think tanks losing their edge in policy debate?

Some think tanks are prioritising a more open approach to policymaking. But this raises the question of what comparative advantage think tanks have. Thanks to digitalisation, other actors have jostled into policy debate, opening up a discussion about what think tanks’ distinctive offer to policymaking is today.

Monica Tan is Director of Communications at the Australian think tank Beyond Zero Emissions.

“Think tanks these days have to be extremely savvy about the media, but also about the world of finance and industry and government. Politics is a fast moving beast,” she says …

So alongside embracing the new pace of policymaking, thinktankers need new skills. In Saqeb’s words, “in many respects policy experts are their own think tanks.”

“They have a public profile to maintain. They’re [administrators] of research. They’re trying to chase funding, they’re trying to maintain a profile for themselves and the organisation that they are representing. And essentially they are trying to position themselves as the go-to person for their expertise.”

For Victoria, who decided that her organisation needed to foreground the voices of excluded communities in Wales, what her team needed was “a high appetite for risk” and “a funder who was willing to back us”.

Victoria in Wales and Iryna in Ukraine agree that empathy is a key skill for researchers today. As Iryna points out, we all have biases.

We have certain biases. And it is important not only to check our data, and our materials, and the people that we interview for biases, but also ourselves.”

Iryna Shyba, DEJURE Foundation

Victoria says that, when recruiting, “the standard interview question for us is, ‘How do you engage with people who aren’t like yourself?’”.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus pandemic has dramatically accelerated some policy debates and stalled others. It has made previously unthinkable interventions in our economies and societies a reality.

In Monica’s words, “the turnaround time for new research and projects is really compressing. So for us, making each thing we do really count” is essential through “strong collaborations” and the help of “implementation partners”.

The scale of the climate crisis, too, means that think tanks could have something new to offer. Reuben says his organisation takes on the implementation itself.

The mental model that I use is of scaffolding. The scaffolding can be provided by outside entities, like think tanks, like government support functions within consulting firms

Reuben Abraham, IDFC Institute

The new agenda for policy organisations

Think tanks adapted quickly to the pandemic. They’ve offered essential analysis of the evolving situation, and important insights into the policy questions it’s opened up.

Policy expertise is more crucial than ever, but policy experts must face a daunting operating environment. And the broader reshaping of the policy landscape demands a new agenda for policy organisations.

They must answer difficult questions about their broader responsibilities. What is their relationship with democracy? Are they neutral with respect to the rules of the democratic game, or do they have responsibilities towards the preservation of democratic standards?

As Robin Niblett, Director and Chief Executive at Chatham House, says:

“Think tanks must consider whether it suffices to try to remain sources of objective debate and analysis, or if it is time, once again, for them to adopt a more proactive stance, being explicit about the principles that they believe should underpin peace and prosperity.”

Think tanks must consider … if it is time, once again, for them to adopt a more proactive stance, being explicit about the principles that they believe should underpin peace and prosperity

Robin Niblett, Chatham House

Our conversations with nominees for the 2021 Prospect awards show that many think tanks already have answers to these questions. They are doing different things, and doing things differently. Some think tanks may keep trying to influence a small circle of political insiders, but others are actively engaging an increasingly vocal public. Some experts might sit back and simply ‘provide evidence’ for others to mobilise, but many are standing up and taking an active role in shaping our societies.