Think tanks and research institutes are producers of knowledge and ideas. Such organisations used to be a western elite club, but have now proliferated all over the world. In many places, they are part of a country’s vibrant civil society – free to speak out, offer alternative sources of information and analysis, and hold their governments to account.

In fact, much of their value remains in their being one step removed from making the changes they propose (even those institutions which like to claim they are ‘do’ tanks). Policy and research organisations – such as think tanks – live in the intersections between policy actors. They use this vantage point to highlight challenges and opportunities that lie beyond the normal policy horizon, or that simply can’t be seen when you’re “in the thick of it”’ (as they say in the UK), looking after the day-to-day business of government.

In this sense, there is much that hasn’t changed in the business of think tanks. What has changed is the information environment that surrounds them and the way they pursue business of debating and sharing ideas.

Transmission is faster, debate is hotter, and the lines between actors blurrier. So if you are fortunate enough to be independent, you have a responsibility to get your ideas out there.

Now, transmission is faster, debate is hotter, and the lines between actors blurrier. Think tanks have their own communications and media platforms; media platforms cultivate politicians; and politicians cultivate their own think tanks.

We might feel more comfortable if the dividing lines were clearer. “You can’t be independent and influential”, a colleague of mine once said to me, perhaps reflecting this very desire to delineate. But I completely disagree. My view is that if you are fortunate enough to be independent, you have a responsibility to get your ideas out there and make sure they are influential.

Making openness a founding principle

Of course, if policy organisations are going to influence policy, they need to consider their standpoint. Ideally, they should be guided by a set of principles that they can stand by over time. At Chatham House, we looked to our history. It gave us principles such as promoting open dialogue, supporting accountable governance, and pursuing, where possible, international cooperation over zero-sum competition between nations.

Let’s look at the first of these. Chatham House was founded in 1920 with the belief that secrecy in diplomacy was one of the root causes of the First World War. And so leaving the development and execution of foreign policy exclusively to diplomats and government officials – acting in secret – increased the possibility of misunderstanding and conflict.

You see this belief in practice in the Chatham House Rule. This creates the space in which you can have trusted conversations. Diplomats can share something that might be secret while protecting their identities, and that means you can get this information out to a wider audience that would otherwise have remained secret. Conflict may still be unavoidable, but its drivers can be debated and challenged by a diverse group of stakeholders in the outcome.

Openness is as practical as it is principled

This idea of openness, of widening access to information in the field of diplomacy, was radical at the time of Chatham House’s founding. But today we are flooded with information, and the challenge is not access but discernment.

Think tank proposals are not, in fact, a detached part of an elite process. Rather, they tend not to be taken up unless the policymakers think there will be support for them downstream. Sure, you need to have that really trusted conversation in a small working group. But policymakers are unlikely to really hear the idea that emerges unless they think that a larger community will back it.

The work we do to get the public interested – on social media, in broadcast interviews, to break down our ideas to make them accessible – feeds back to the policymaker. And that makes them more likely to believe the thing you’re telling them in private, because they believe they’ll find political support if they follow your advice.

Open communication mobilises action

Think tanks are small, but they have the potential for massive influence. This is especially true in international affairs, where states are the only legal representatives of their societies on the world stage. Governments are preoccupied with a host of complex domestic challenges today, as well as with ever more disruptive international pressures, and this gives space to think tanks.

I think the capacity of governments to drive positive change by themselves is increasingly limited. They have the capacity to defend us from external risks and challenges, but the idea that, if states just strike the right agreements on arms control, climate mitigation or trade promotion, our welfare will automatically increase, has been dramatically disproved. Just look at how segments of our societies have been left behind by offshoring jobs, and how the environment has suffered in the global race for growth.

Talking to ourselves is not enough. Being the top of the pile among other think tanks is not enough. Being regularly quoted in the Financial Times is not enough.

And so even international affairs think tanks have to broaden their audiences if they want to create positive change. Beyond governments, we need to address NGOs, companies, cities, regions and so on. All of this means that in order for any form of policy communications to be effective, you have to be able to communicate ideas that are not just for the elite.

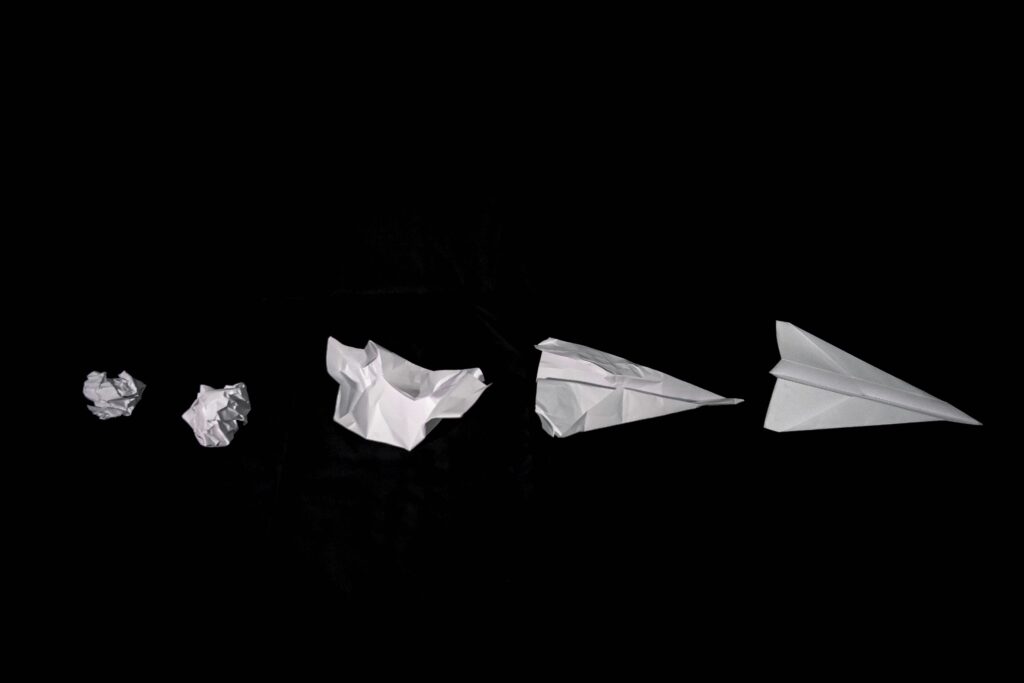

In the democratic world, this is a whole-of-society effort. In this context, policy communicators need to take esoteric ideas from expert organisations and make sure they are relevant to large groups of people.

When large groups act together, we might see progress on climate, on sustainable development, or making our societies and economies more inclusive and equal.

That means that talking to ourselves is not enough. Being the top of the pile among other think tanks is not enough. Being regularly quoted in the Financial Times is not enough.

We have to democratise our best ideas. Policy communicators are at the front line of making that happen.

Sir Robin Niblett is a distinguished fellow at Chatham House after spending 15 years as its director and chief executive until 2022. He is also a distinguished fellow of the Asia Society Policy Institute and senior adviser to the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) in Washington DC. He is also principal of Ledwell Advisory, a risk advisory company. Robin is recognised as a leading expert on the relations between Europe, the US, and Asia and their implications for risk management by governments and private institutions.