Yet both the policymaking sector and academia can be opaque when it comes to communications. So it’s unsurprising that their comms efforts often follows suit.

But we think policy and research organisations must broaden the reach of their work so that public policy is developed in dialogue with … you know … the public.

This is not just a matter of principle. Practically, social media means the public is a far more active player in political discourse than when many research organisations were first founded.

A policy is viable only if enough people have an appetite for it. Otherwise, it’s an uphill struggle the whole way. So if you want your research and policy advice to be effective, communications – especially to the public – must not be an afterthought.

This piece will give you three ways to work with this awareness and shape more effective policy and research comms: by thinking about your research communications in terms of impact, by centering the story not the report, and by connecting with the humanity of your work.

Forget “research” and “comms,” think impact

This simple but effective reframe comes from Helen Dempster, who has worked in think tanks for many years. Here’s why it matters.

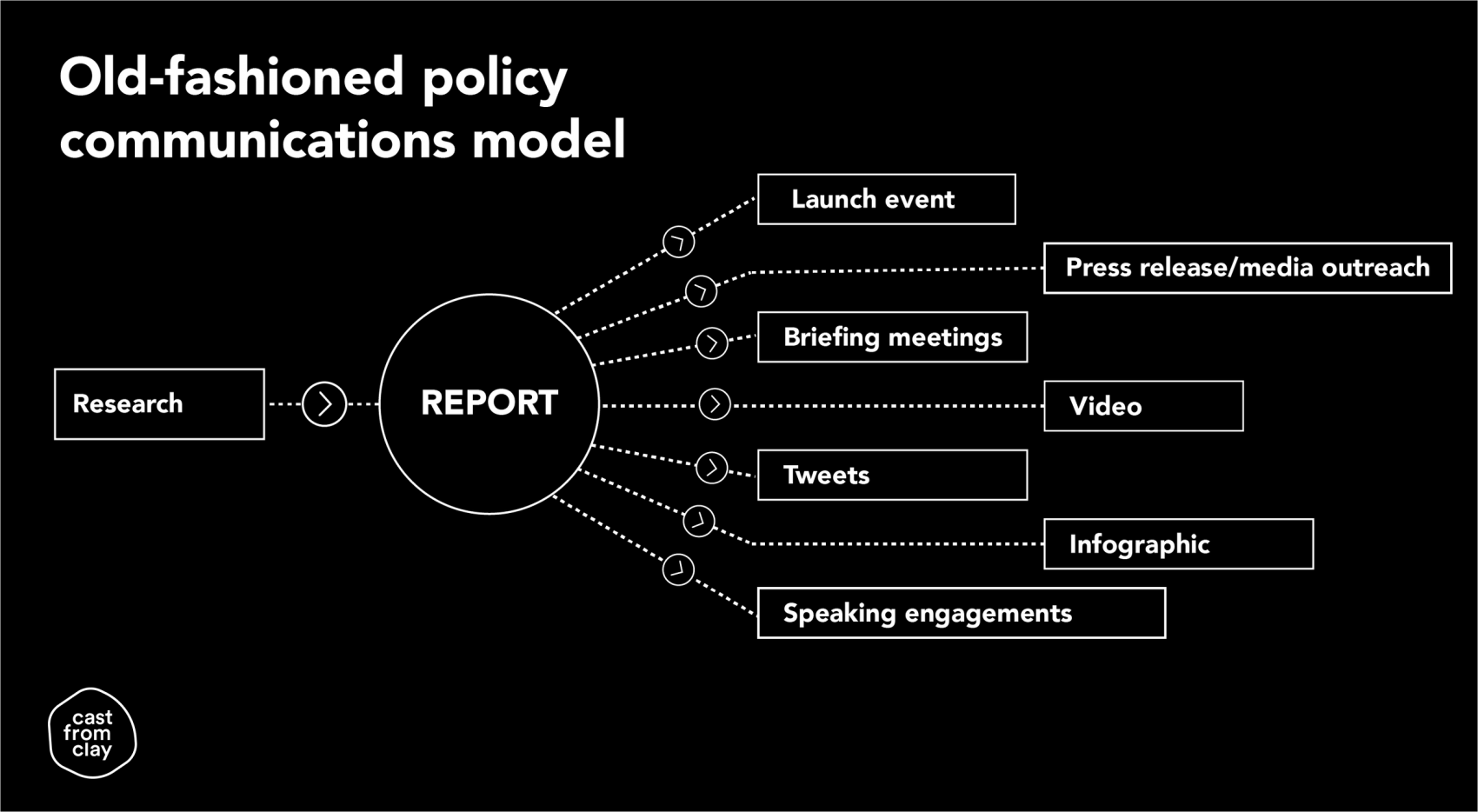

We can consider research communications in two models.

The traditional model is a bit like a standard restaurant. Researchers are like the kitchen team – they cook up the research. The comms team are like the front-of-house staff – they engage with the customers (their audiences) and serve up the food. This is an acceptable model, but it has its flaws.

The customer-facing team might not know much about how the food is prepared. This means they may struggle to explain in an engaging way how the food was sourced and why it was cooked in such a way – both important for the overall food experience. Meanwhile, the kitchen staff don’t always get a chance to hear when something is delicious. Plus, when they hear complaints they’re second-hand and easy to dismiss.

And for the customer? They usually don’t know who is cooking their food or how they’re cooking it, meaning there’s always the fear it might have been handled with a lack of care and attention.

Now let’s imagine an alternative model.

This model of policy and research communications is like a more up-market restaurant. Here, the front-of-house staff are an extension of the kitchen. They may have been involved in shaping the menu – in-part based on customer experience – and will certainly have tried every dish. They know where the food is sourced. Maybe the chef makes an appearance at some point in the evening. In some really swish places, the kitchen might even prepare the food in front of the customer while they, or the service team, explain the process and pick out tasting notes.

In the first model, the priority is efficiency. How many tables can we flip? How many research reports can we publish? You can achieve this through a division of work whereby cooks and front-of-house can each specialize in one field of expertise.

Bringing comms in at the very nascent phases of a project helps decide: What outcome do we want from this work? Who do we need to reach to make this happen?

In the second, the focus is impact. People leave knowing more about flavour and food than when they arrived. The team are viewed as experts in what they do. Customers come back again. They recommend your restaurant to others and word travels.

When you rethink comms as impact, you’re shifting from the first model to the second model. The team is working together to get the best possible outcome for the customer.

Taking this approach might involve making structural changes to your team and processes, to learn new skills and adapt how different parts of the team collaborate. Structurally, it could require a different funding model altogether.

But at the very least, it involves bringing comms in at the very nascent phases of a project to help decide: What outcome do we and the customer want from this work? Who do we need to reach to make this happen? How do we shape the messaging to help make sure the work travels?

Try it today: Do you have a “comms planning meeting” coming up for a new research product? Try changing the name of the meeting to “impact planning meeting”. See how that shifts the team’s approach to the discussion.

Read more about embedding communications into your research processes.

Decenter your report, center your story

Thinking about impact means we think differently about outputs.

The traditional model of policy research communications treats the report as the hub for all of the research, around which all communications centre.

There’s good reason for that. The report is where a lot of the thinking happens, and the hypothesis gets hammered out into a narrative. But what you gain in precision (ensuring that every point is caveated and nuanced) you lose in the number of people you reach. Treating the research report as the output of your work drastically undervalues your efforts.

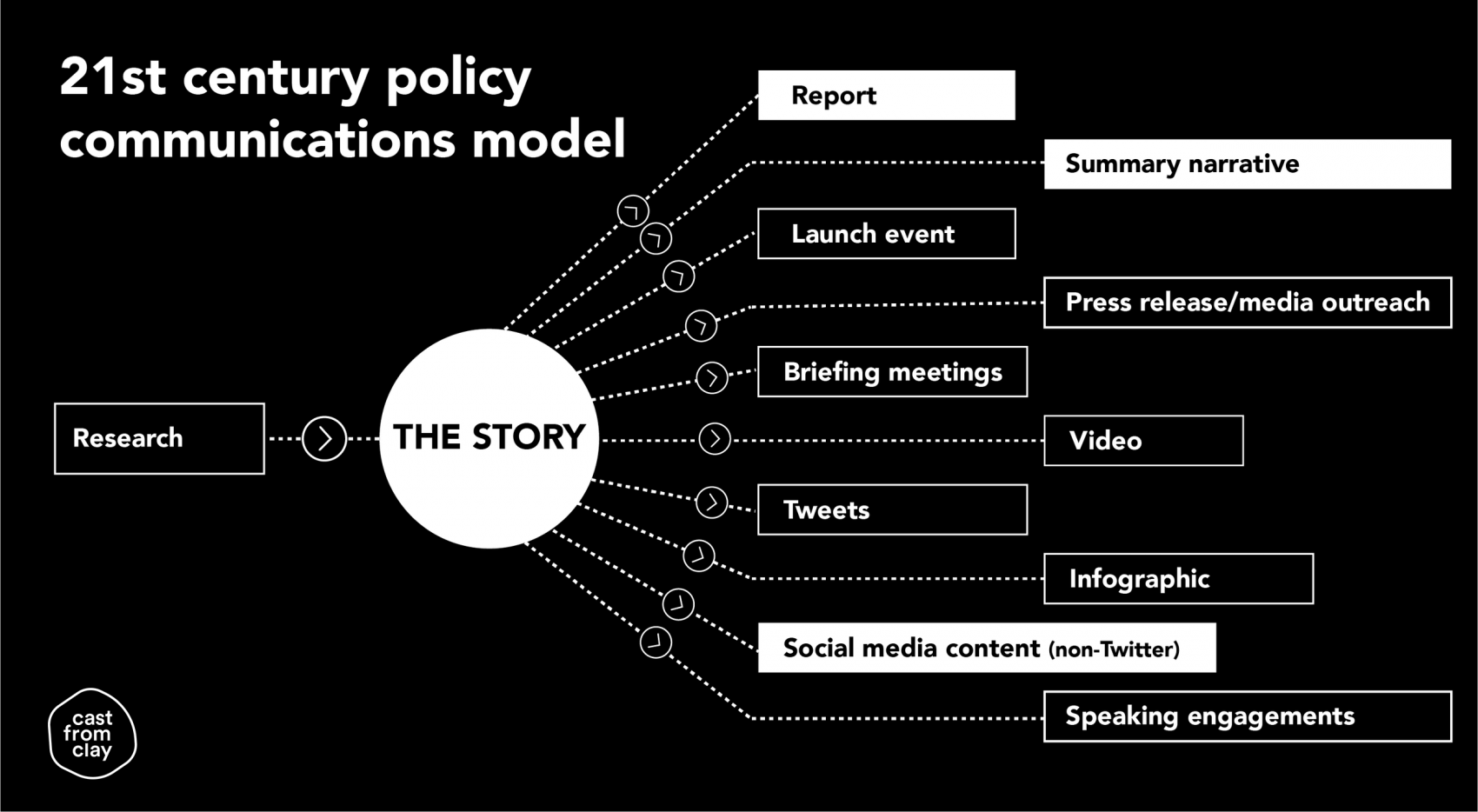

We think it should not be the report but the story that is centred.

Here, we centre the story – what the research found and why it matters. The research report is still important, but it is supporting evidence for the bigger story that your research is telling. The story covers not just what happened (the factual occurrences) but the significance, the connection to a broader context, and the journey forward.

The way this then translates into communications may feel subtle, but the intention is different. Rather than seeking to draw your audience to explore the report (“Read more here”) you are seeking to take your report findings to your audience through a range of formats and platforms.

You then have the option to tell your story over time, to varying levels of depth and detail and to different audiences, rather than launching with a splash on one day and then moving on. Getting to the story of your research requires you to distil the meaning and significance of the work, meaning your research communications will have more salience and, hopefully, more impact.

Try it today: Start playing with the story structures we know and love to start thinking differently about your research outputs. Can you map out what your current project is saying using Freitag’s pyramid, for example? Outline your exposition, tension, climax, falling action, and resolution to form your tale.

Learn more about centring the story in your research communications here.

Think like a person, not a researcher

To tell an effective story, we have to connect with the human elements of our work. That’s because stories are inherently human – they are still humanity’s greatest vessels for sharing knowledge and generating collective wisdom.

We often forget this in research and policy development. We see the value of this work as being impartial, rational, and evidence driven. That has its value to a point. But it means there is a general culture around research and evidence development divorced from the literal purpose of policy. Which is: to make life better for people.

We think that if we remain in touch with the human purpose of our work, everyone benefits. That means connecting with the humanity of the people impacted by the policies you’re discussing.

At Cast From Clay, we think that if we remain in touch with the human purpose of our work, everyone benefits. That means connecting with the humanity of the people impacted by the policies you’re discussing. Including their stories, testimony, and case studies.

But it also means including the humanity of you, the people doing the research. Connecting in with why this research matters to you, why you’re excited by it or motivated by it, which eureka moments happened for you or where you feel stuck. These are all valuable contact points for your audience to help relay the significance of your research.

Take the moment the CERN scientists announced the discovery of the Higgs Boson particle, for example.

When I watch this video, I have no idea what the figures mean on the board, or what the man announcing it is saying. The expert science is beyond my comprehension. But the emotion in the room is palpable, such that I still tear up when I watch it. The smiles, the rapturous applause, Peter Higgs in the crowd wiping his tears. This, I can understand. And it tells me: this is important, this matters. Because – and this is something we often forget in research communications – emotion is information.

This is something we often forget in research communications: emotion is information.

As my colleague Natallia wrote recently: “… policy experts and researchers often try to create a sterile environment of data to inform those in power. But what if we were to leave the fingermarks of those who collected this data and those whom it represents? Could it help these meanings to find their way into our everyday meaning-making?”

If you can step away from the detail of your work and the deadline for your report and ask yourself: “Why does this matter to the people it concerns?” and “Why does this matter to me?”. That’s where you find your story. And when think tanks can tell a clear story about the work they do, we can begin to shape the evidence-based and human-centred policies we all deserve.

Try it today: Explore new dimensions of a current project by asking yourself or your colleagues a question like: “What stood out to you in this work?” “Did anything make you excited, angry, sad, energized?” Think like a journalist looking for a “human interest” story.

Find out more about how to build storytelling into your work here.

A version of this article was originally written and published for the Think Tank Lab’s Think Tank Toolbox. Explore the full resource.