Our response to the Covid outbreak was shaped by a tapestry of expert advice – from virus control and immunology to economic forecasting to marketing and behavioural insights.

Complex democratic societies require expertise to make good decisions. However, expertise seems to be back on trial, as some politicians have started questioning their government’s over-reliance on experts during the pandemic.

We’ve known for some time that the trustworthiness of evidence is determined in part by its messenger, and which agenda they are perceived to promote.

What’s new is that we now live in a world where at least two society-wide realities co-exist in parallel: let’s call them ‘mainstream’ and ‘alternative’. They live side by side, but rarely meet. Each has its own narrative, its own media, and its own sets of facts. They are both characterised by mistrust for the other. And on the occasions when they do come face to face, it’s often explosive.

In a confusing world where you can find facts to support just about any argument, we end up deferring to our gut to make the decision on whether to trust, or not. This is surely the culmination of a now fully fragmented public sphere. The final phase of the journey from an Age of Reason to an Age of Instinct.

Many in the policy sector predicted it. We now need to come to terms with its realisation.

Part 1: Policy experts are avoiding the elephant in the room

Policy experts have the power to shape the world. And yet, as a sector, we seem to have largely carried on with our own activities as if this change to the information environment in which we find ourselves were just a temporary state of affairs. We’ve tinkered round the edges as if minor adjustments were enough, but avoiding the elephant in the room:

- How can one be an impactful policy expert in a world where instinct trumps reason?

- How can we claim to inform the public debate when the information environment is irrevocably fragmented?

- How do we square being part of the solution to improve society through good policy design, when we are not able to draw on the personal experience of much of the population?

Part 2: This is not about a pro-democracy mainstream vs an anti-democracy alternative

“…democracies need committed citizens who believe in the wider democratic ideals of distributed power, rights, compromise and informed debate.”

Jamie Bartlett, in The People Vs Tech (p.3)

There is no doubt that the fragmentation of the information environment is a challenge for policy experts. Their business model requires a unified public space to support an informed debate, and enough trust between sides to agree on what constitutes fact.

Yet to think of this fragmentation as a pro-democratic mainstream versus an anti-democratic, populist alternative is reductive. It is important to recognise that both narratives argue they are protecting democracy against the other.

Our research shows extensive support for democracy across America.

68% of US citizens state they support democracy, and 58% have found their support of democratic rights reinforced by Ukraine’s fight to defend its own.

It is also clear that we are united in valuing a healthy information environment that allows informed debate, and is supported by expertise, as cornerstones of a functioning democracy.

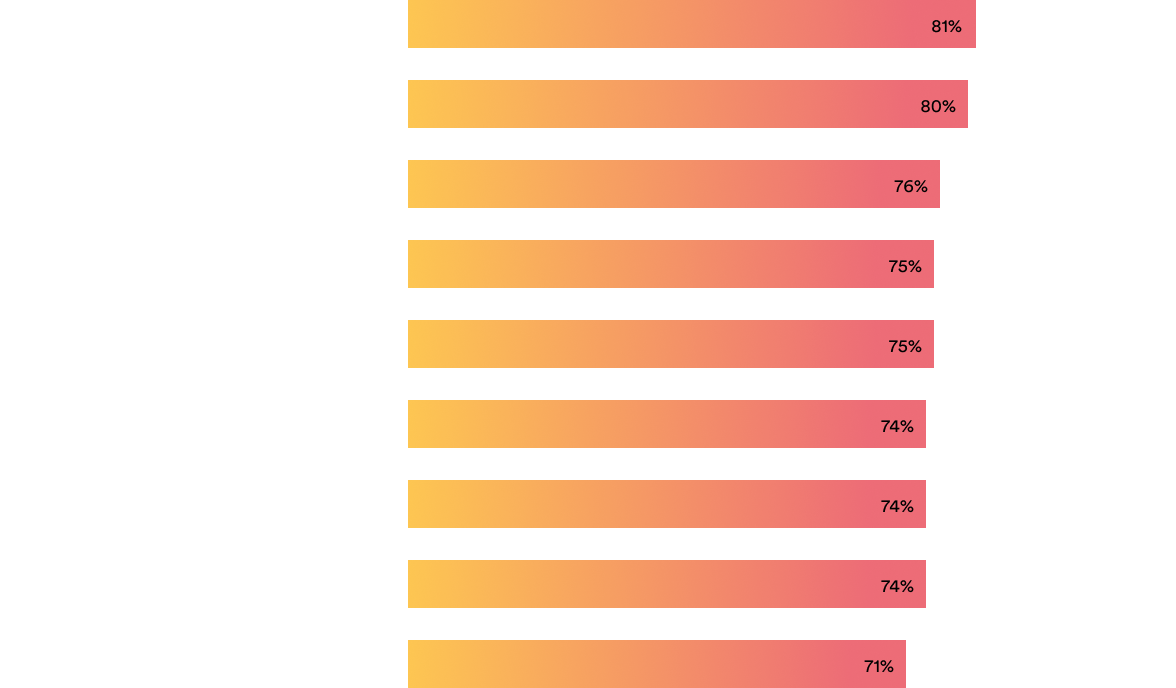

A healthy information environment and expertise are seen as key to democracy

How valuable do you consider the following to a healthy and fair democracy? (Valuable, Extremely valuable)

However, dig a little deeper and these foundations are shaky.

We segmented respondents by their political engagement, including Insiders, i.e. people who work in politics or public policy and Spectators, i.e. people who are interested in politics (See ‘Our Methodology’).

We found that 65% of Insiders admitted that they feel they should care about democracy but don’t (compared to just 34% of Spectators). Such a finding raises the question: do political and policy insiders believe in the very system they inhabit?

Meanwhile, 47% of the US population now prefer getting their information from alternative sources, rather than mainstream news (only 24% disagreed).

This begs another question: isn’t the challenge to policy experts less the rise of populism – which is arguably more of a symptom – and more the fragmentation of the shared public space for informed debate?

Part 3: The information environment that spawned civil society is no more

30 years ago, the struggle was in finding information. The struggle today is one of filtering, and finding meaning.

Between the avalanche of fake news, the onset of deep fakes, and access to enough facts that would support just about any argument you want to make, our information environment is under stress – 71% of American citizens admit to struggling to tell what is true anymore.

And this is not just the general public. Our research shows that Insiders struggle to identify facts just as much as Spectators, if not more.

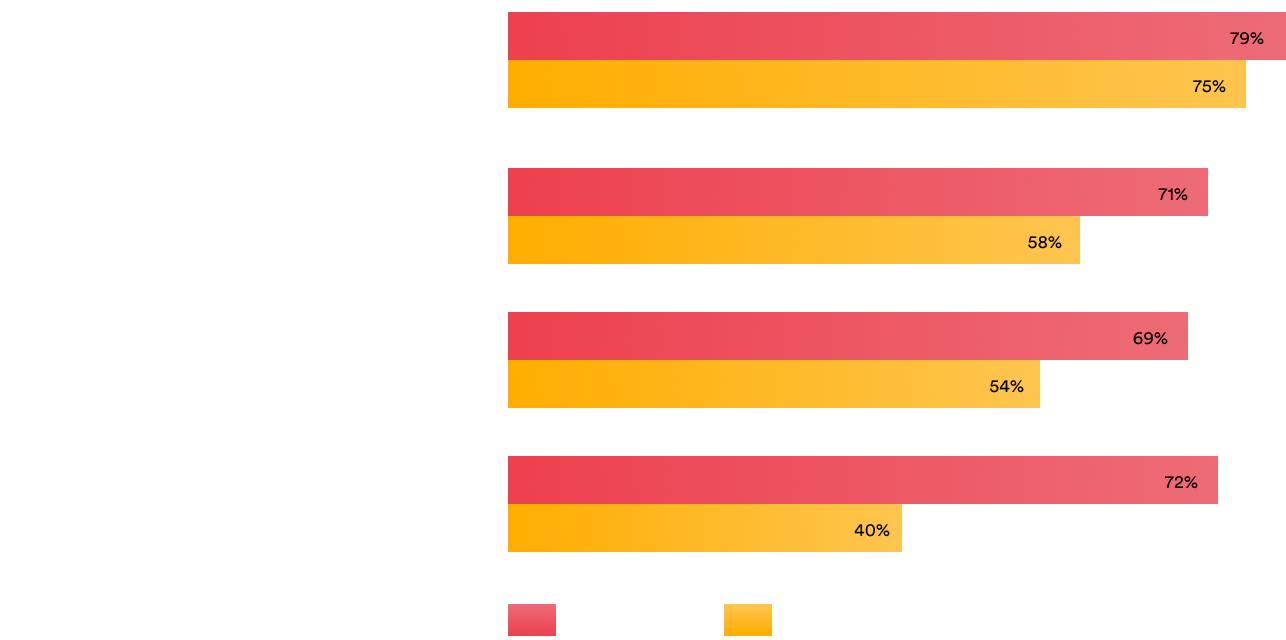

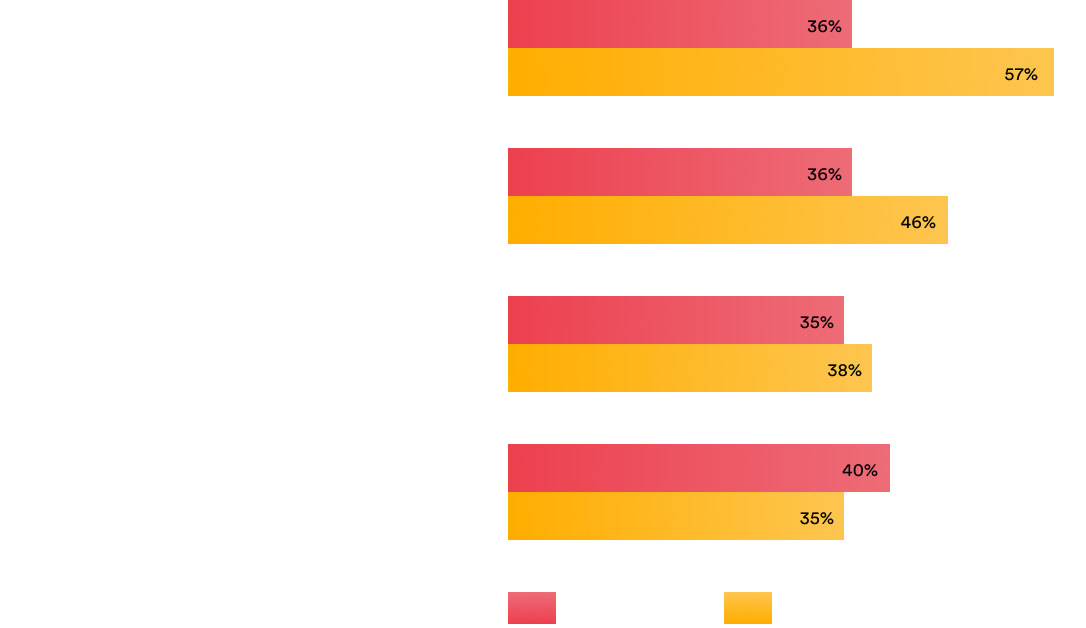

Insiders struggle with facts or truth even more than the public interested in politics

Please indicate your level of agreement with each of the following statements (Agree, Strongly agree)

Is it any surprise then that in the absence of certainty, many fall back on ‘common sense’ and personal experience?

When asked what influences their views or decisions about politics, the most popular answer among American citizens was ‘things I’ve seen or experienced for myself’ (52%), with expertise a distant second (38%). Personal experience also came second for Insiders (36%), behind ‘people like me’ (40%).

And we expect common sense and instinct from our politicians. 45% felt politicians placed too much emphasis on evidence (though 23% disagreed), while 41% wanted to see more common sense in politics (28% disagreed).

It seems the current information environment is pulling the rug from under our feet.

Part 4: Experts can shape the information environment by redefining their role

“[Experts] need to put a lot of attention into earning the trust of society, something that’s been lost … This involves taking seriously the need to have a much better discourse with the rest of the population.”

Prof. Sheila Dow, Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Stirling University

The good news is that even in the current information environment, experts continue to have a mandate in the eyes of American citizens, for now at least.

54% of the population felt experts supported informed democratic debate through high-quality information and insight, with only 15% disagreeing.

Their role in advising government also endures, with 71% of the US public seeing this function as necessary for a healthy democracy. And Insiders agreed: 72% of them found think tanks and public policy experts valuable to society.

But if the political class continue to be perceived as promoting the agenda of ‘urban elites’, is this enough?

It won’t come as a surprise to anyone who follows our work that, in the current information environment, we think policy experts need to go beyond government advice and convening in the Beltway.

74% of the American public also saw a role for experts to advise the public. Interestingly, Spectators were slightly more likely to name experts as influencing their political views and decisions, than Insiders.

Spectators are more likely to trust experts than Insiders

Which of the following influence your views and decisions about politics? (Select any that apply)

We found that the top markers of expertise were: ‘years in the job’ (47%), ‘having personal experience of the topic’ (44%), and ‘impartiality’ (42%).

Conversely, the main reasons to distrust an expert were: ‘suspicions of a hidden agenda’ (50%), ‘a feeling that what they say isn’t clear or doesn’t make sense’ (46%), lack of transparency in funding (44%).

It is more important than ever for experts to cultivate their reputation – both as organisations and as a sector – to be seen as a bridge rather than a vehicle for the elite.

The way ahead: Recognising the paradigm shift

“Democracy… is like Tinkerbells’ light. If you stop believing in [it], it dies.”

Penny Mordaunt MP

The policy sector is at a crossroads. The current information environment is a challenge to the very notion of policy research and expertise as we understand it. And yet policy experts have, to date, mostly turned a blind eye to the foundational nature of this shift, and its implications for their role in healthy democratic societies.

The sector’s answer has been to make tweaks within the existing paradigm: new formats, more accessible, broader outreach. Some, more bullish, have suggested the answer to be to “double-down” on what they know: i.e. more research, more robust methodologies, more impartiality, more convening.

This avoids the rather trickier prospect of recognising this paradigm shift for what it is: the information environment that spawned civil society no longer exists.

The public sphere has irrevocably fragmented, and parallel realities have formed. The notion of true feels out of reach.

The shift is foundational, and it’s here to stay. We will not return to the old equilibrium once the argument has been won. This is our new equilibrium, and we need to learn to live with it.

Short to medium term, working with the information environment may involve nurturing a new cohort of more outwardly-focused, media/social media-savvy experts to guide the public debate. Funders will need to recognise this shift and support genuine public engagement efforts.

Long term, reshaping the information environment will require social scientists to bridge the gap with the public, and find a way to reconcile their methodologies with personal experience. Policy organisations will need to have resolved the issue of inclusion in the sector, to make sure the views in its workforce are representative of the population.

This could take time, but the clock is ticking. So as an immediate first step, let’s start by recognising this new Age of Instinct for the paradigm shift that it is.

Our methodology

Cast From Clay interviewed n=1,011 American adults aged 18+ in July 2022, via online panel survey, on their perceptions of democracy, facts, expertise and the information environment.

Audience segmentation by level of political engagement

Respondents were screened and weighted to be nationally representative of age, gender and region. The margin of error on the study is +/- 3.1%.

We further applied our segmentation on levels of political engagement.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS with us!