The relationship between think tanks and democracy is not always clear. Certainly, think tanks have played a critical role in younger democracies – but in the more mature Western democracies, the picture is more mixed.

Either way, it seems clear that policy organisations generally flourish in free, open, pluralistic societies. So it is worth exploring the question of the health of our democracies, and whether think tanks have a role to play in their upkeep.

Democracy under threat?

Events in the so-called Free World over the last 10 years have raised the question of whether Western societies’ commitment to democracy is faltering. Key institutions – judiciary, legislature, media – have found themselves under attack, and elections have been called into question.

We’ve seen unrest in Hungary, Poland and Italy, but also in the US and the UK, previously bastions of democratic stability. And in France, the 2022 presidential election in France is shaping up to be a plebiscite on French mainstream politics.

This raises a key question: to what extent does this reflect a genuine change in public attitudes towards democratic governance? Have the public genuinely fallen out of love with democracy?

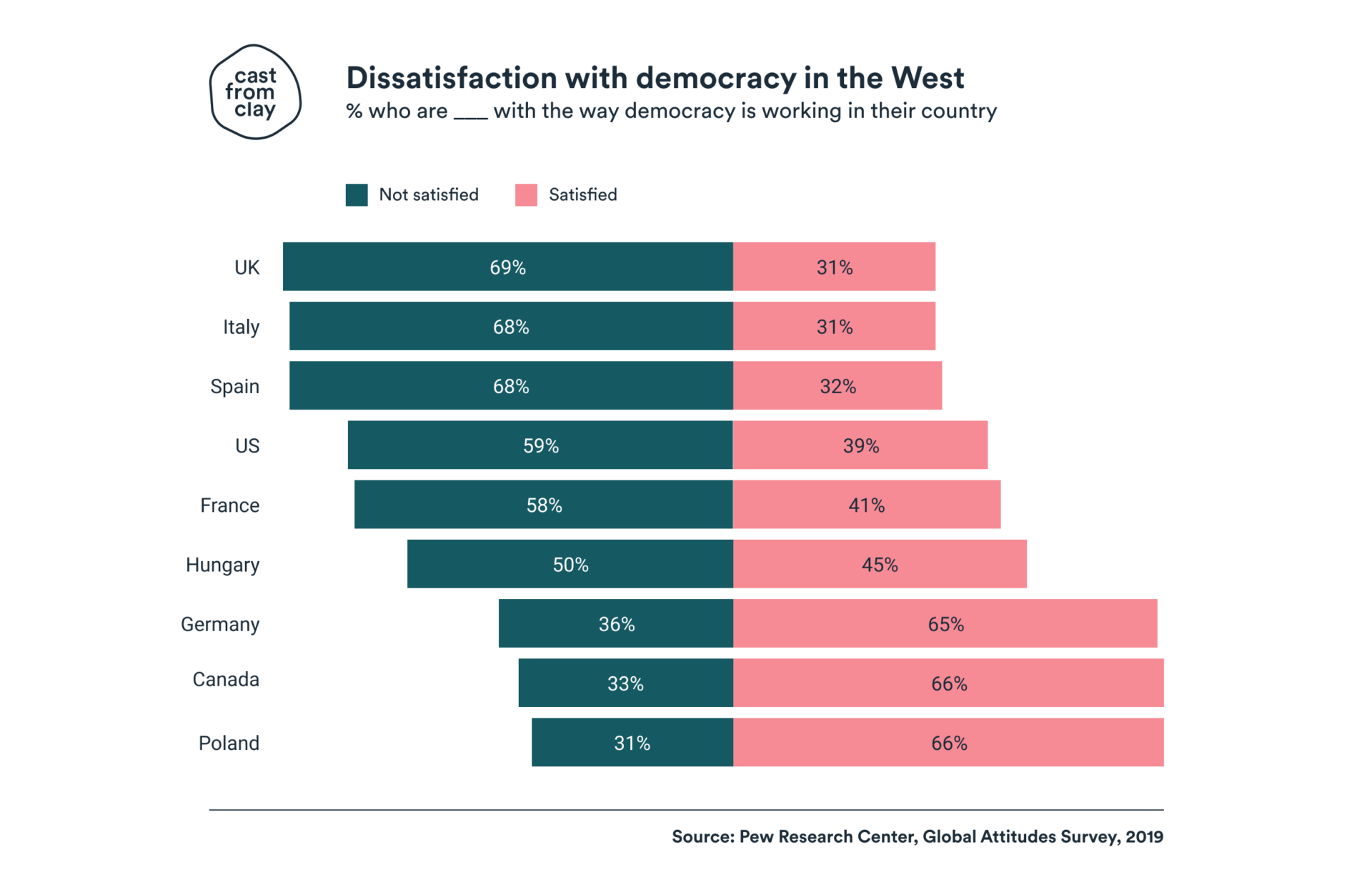

There is certainly evidence that the general public is dissatisfied with democracy. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Survey 2019 found that 69% of people in the UK did not think democracy was working.

Latana and the Alliance of Democracies’ Democracy Perception Index suggests that the political environment is most volatile when there is a large gap between how important democracy is considered to be, and how democratic the country actually is.

The problem seems clear – it is the practice of democracy, more than the ideals of democracy, which seem to be causing discontent. And as we know, the practice of democracy is messy.

On a day-to-day basis, governments have to balance due process with political efficacy. Free speech with disinformation. Rule of law with security against terrorism. International laws with perceived national interests. The list goes on.

So, how do we feel about these trade-offs? The next section explores how the general public in the UK feel about these trade-offs.

Public support for democracy is not unconditional

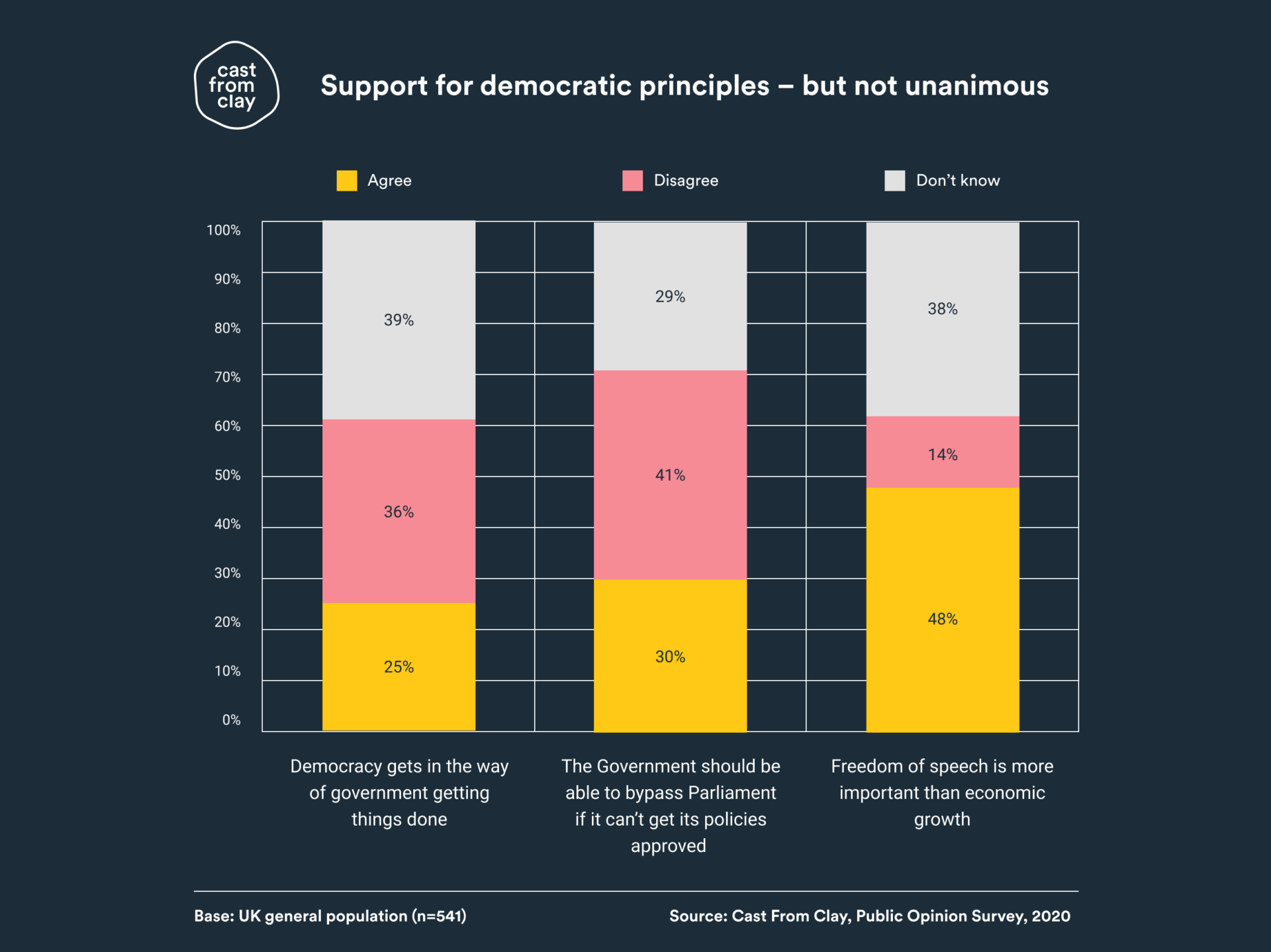

Last year, we asked the British public a number of questions around how they felt about democratic principles, and the trade-offs which come with running a democracy.

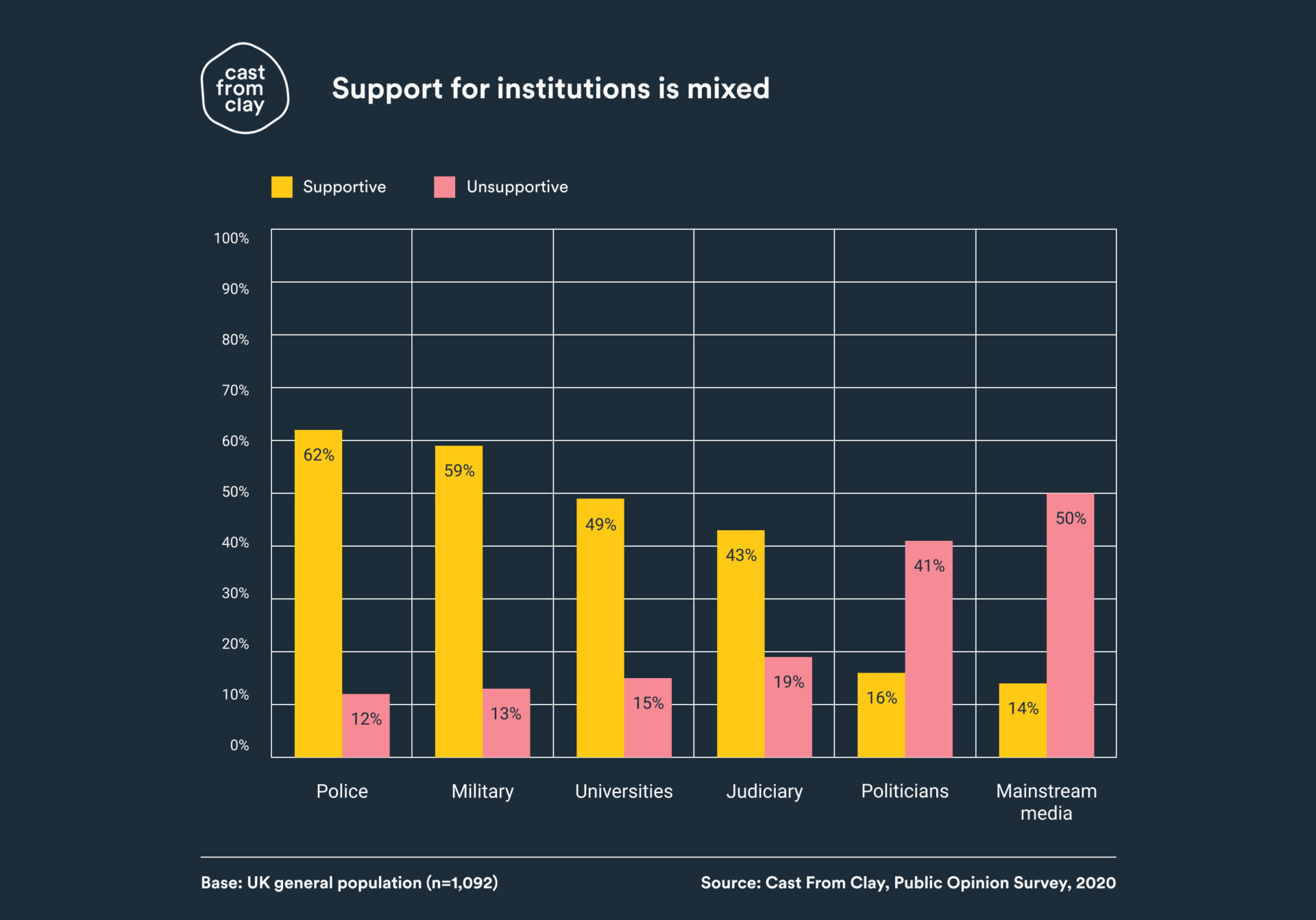

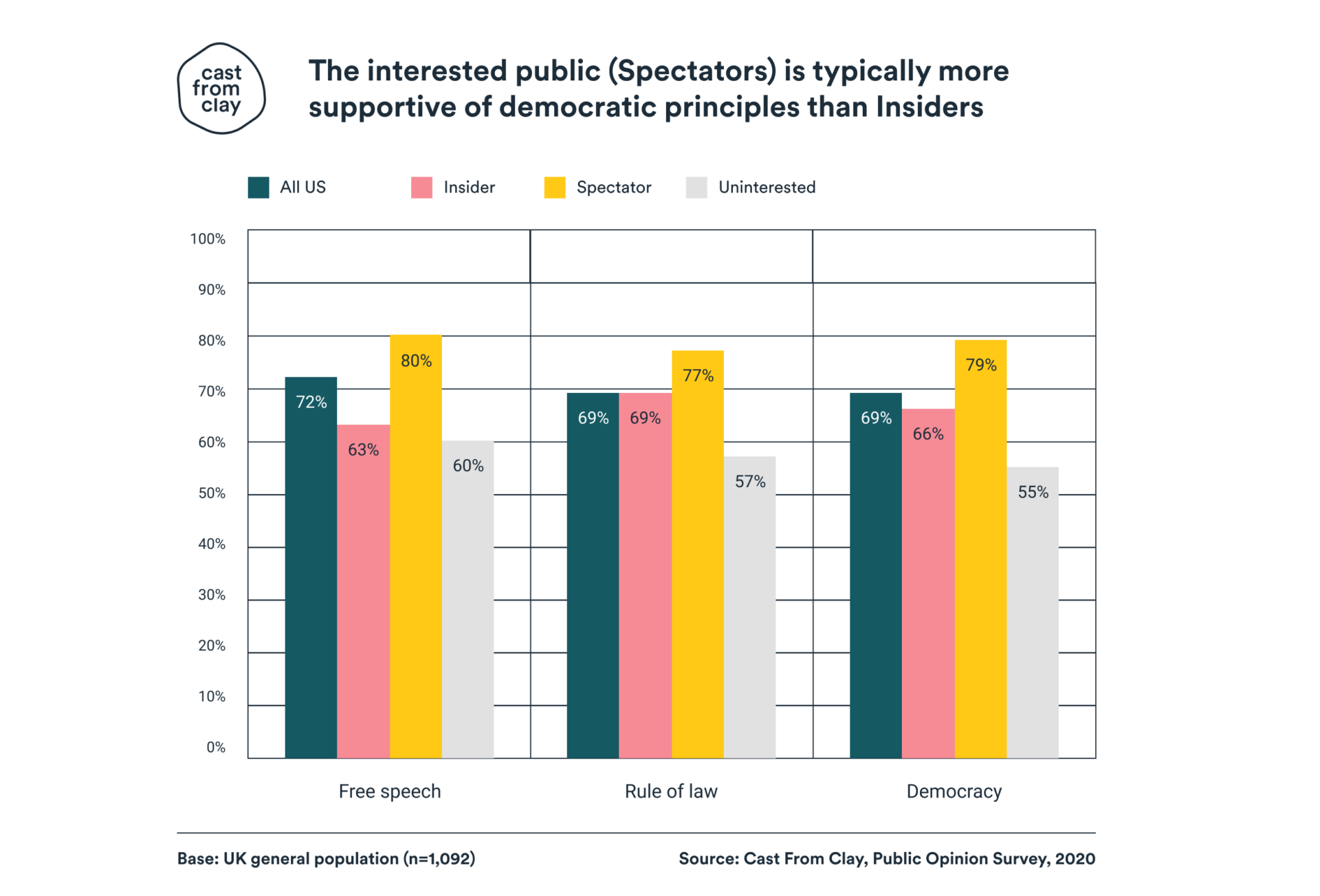

Overall, we found that while trust in the political system was low (31%), the public’s commitment to democratic principles remained surprisingly resilient. Over two-thirds (69%) expressed support for democracy, and 72% supported free speech.

However, when we balanced the commitment to democracy against other priorities like government efficacy or economic growth, we found that the British public’s support for democracy was not a blank cheque – many people are on the fence.

As for the rule of law, similar levels expressed support (69%). The military (62%) and the police (59%) were the institutions which received the highest level of support, while the judiciary trailed a little further behind (43%).

Political insiders, not the public, are more likely to question democratic principles

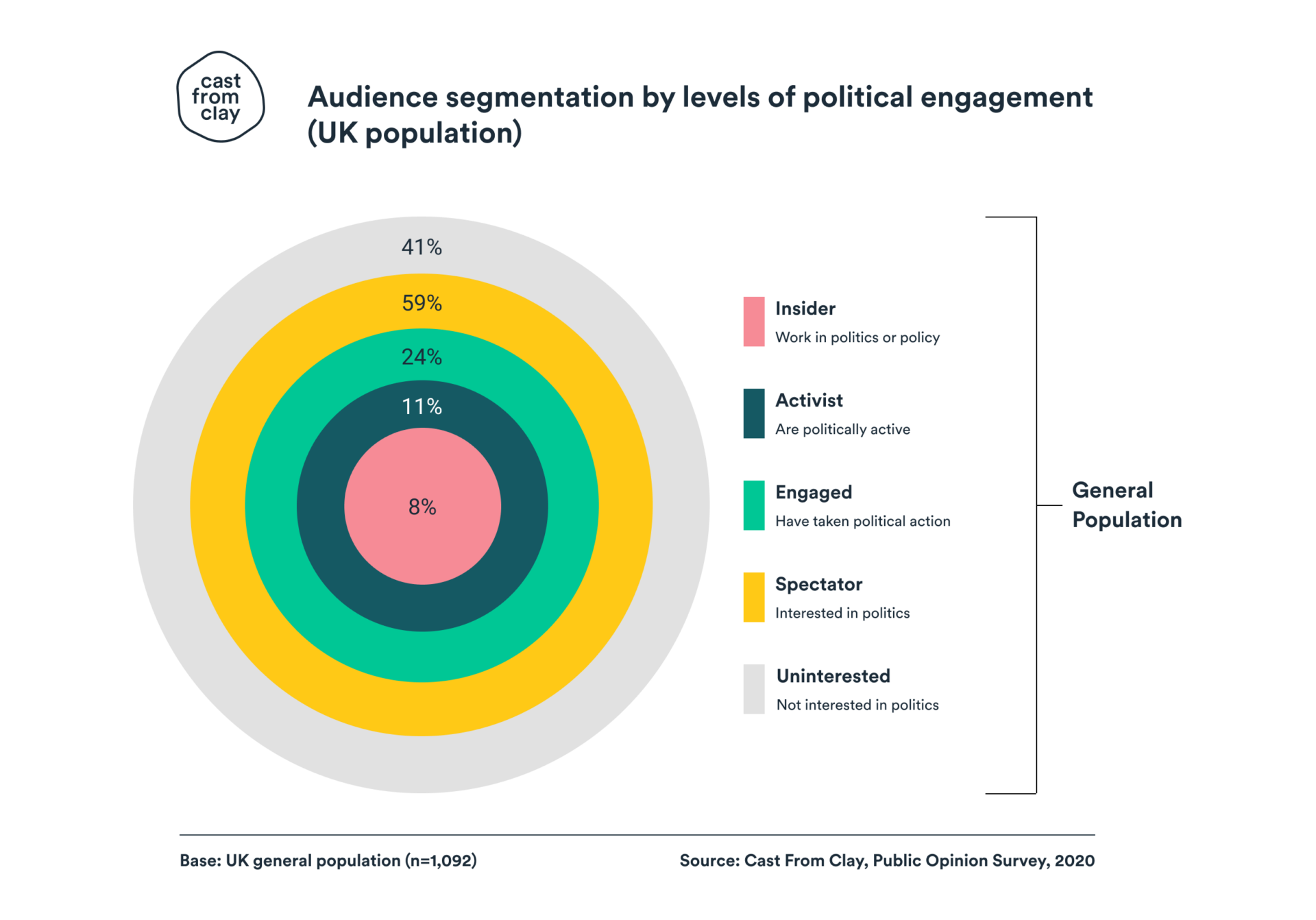

To explore this, we looked at the data according to the audience segmentation we’ve been using for the past few years. We think of concentric circles of political engagement, with Insiders at the heart of the political system, layering out to the wider public.

Unsurprisingly, we found that Spectators (ie, the public interested in politics) were far more likely to support democratic principles than the Uninterested. Perhaps more surprisingly, we found that Spectators were also significantly more likely to support democratic principles than Insiders (ie, those at the heart of the political system).

This was generally true across most of the questions we asked. Insiders were significantly more likely than Spectators to think that democracy gets in the way of getting things done, or that the executive should be able to bypass the legislature.

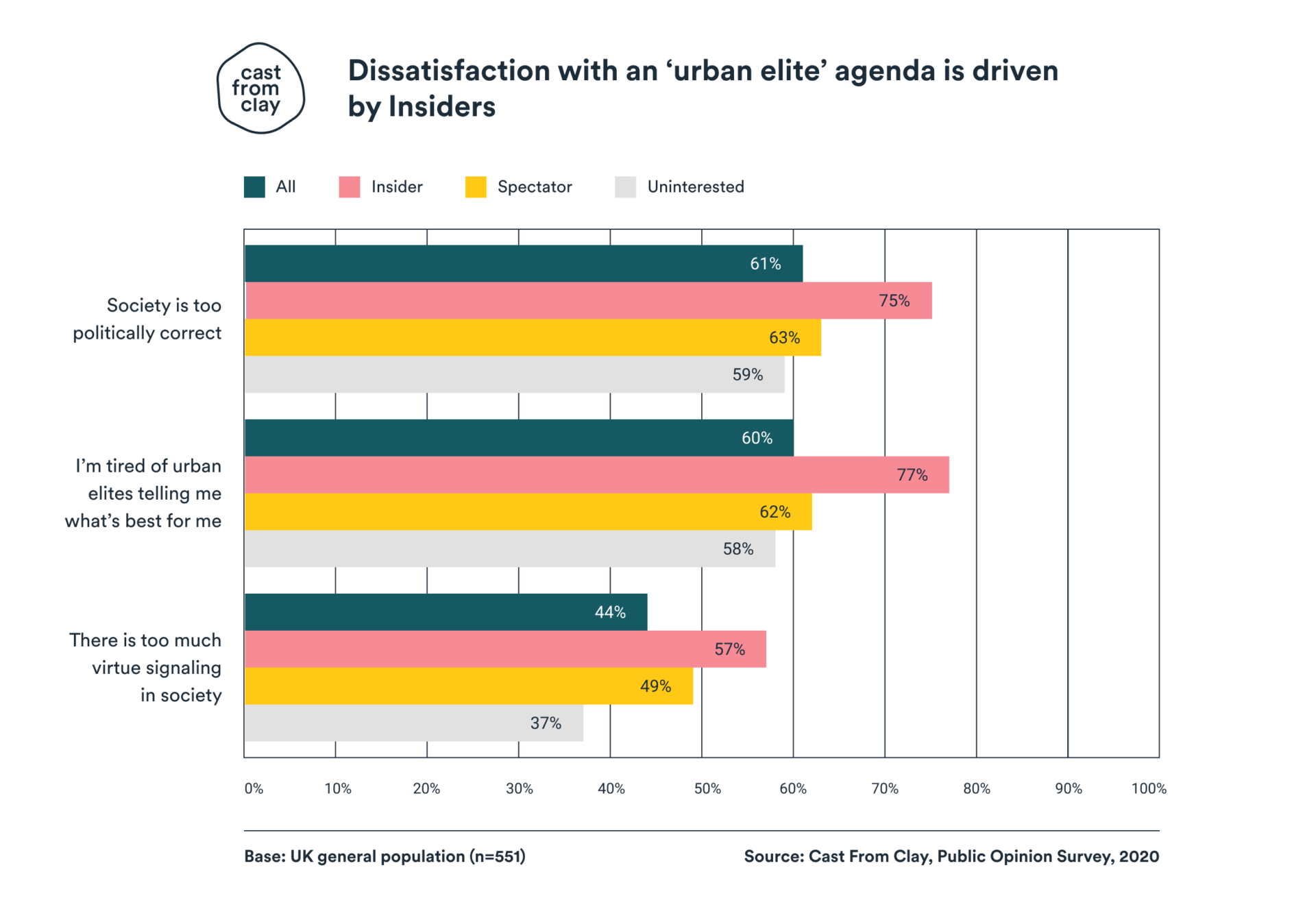

Interestingly, Insiders also came consistently higher than both Spectators and the Uninterested when it came to dissatisfaction with urban elites and political correctness – key drivers among a number of those inclined to vote for UKIP or the Brexit Party.

It is unclear whether this is because Insiders genuinely feeling the issue more acutely, or whether they were projecting how the general public feels – and in doing so, over-estimating the issue.

But these findings align with research from the Policy Institute at King’s College London, which suggests that political and media elites are responsible for driving division, and creating “culture wars”.

In that context, we must guard against over-correcting in reaction to populist movements. While political disenchantment is real – and must be addressed – politicians and the media are reflecting more outrage than the public genuinely feels.

Think tanks concerned with democracy should ally with the interested public

The last 10 years have raised a number of fundamental questions for policy organisations, including: What is our relationship with democracy? Are we neutral, or do we have responsibilities towards the preservation of democratic standards?

For us, this feels like a no-brainer. The maintenance of democracy is everyone’s civic duty – individuals’ and organisations’ alike. The experience of newer democracies shows that think tanks have a leading role to play, and – pragmatically – democratic environments make it easier for think tanks to go about their business.

“We will not recognise the end of democracy when it comes, if it does. […] The rhetoric of democracy will be unchanged, but it will be meaningless – and the fault will be ours.”

Lord Jonathan Sumption, former Justice of the UK Supreme Court

Traditionally, policy experts have tended to think of the general public as volatile, needing the guidance of technocrats to navigate the more complex and nuanced elements of our political and democratic systems.

However, our findings suggest that the informed public may yet be their best ally. The challenge is how to connect with this Spectators segment – with the added benefit that by engaging Spectators, think tanks will become more than Michael Gove’s infamous characterisation as “experts with organisations with acronyms”.

In the BBC’s annual Reith Lectures in 2019, former UK Supreme Court judge Lord Jonathan Sumption reflected:

“We will not recognise the end of democracy when it comes, if it does. Advanced democracies are not overthrown, there are no tanks on the street, no sudden catastrophes, no brash dictators or braying mobs, instead, their institutions are imperceptibly drained of everything that once made them democratic. The labels will still be there, but they will no longer describe the contents, the facade will still stand, but there will be nothing behind it, the rhetoric of democracy will be unchanged, but it will be meaningless – and the fault will be ours.”

Is it enough for policy experts to be bystanders, as our institutions are chipped away? Or is it time to stand up for democracy?