Listen to Katy talk about conspiracy theories and policy in the Synthetic Society podcast.

It’s thought that many believers turn to conspiracy theories because they don’t feel heard or represented by mainstream narratives. For policy experts who believe in evidence-based policy, this is a message of caution.

Understanding conspiracy theories

I don’t believe conspiracy theories (although we’re all vulnerable). But I do believe that not being heard is one reason people turn to conspiracy theories in the first place.

When people concerned about truth and facts and reality hear conspiracy theories their first response is: ‘but that’s not true!’

Of course, truth is an enormous concern – take ‘antivaxxers’ for example, the consequences are potentially deadly. But refutation doesn’t get that far because true/false is only one part of the conspiracy theory picture.

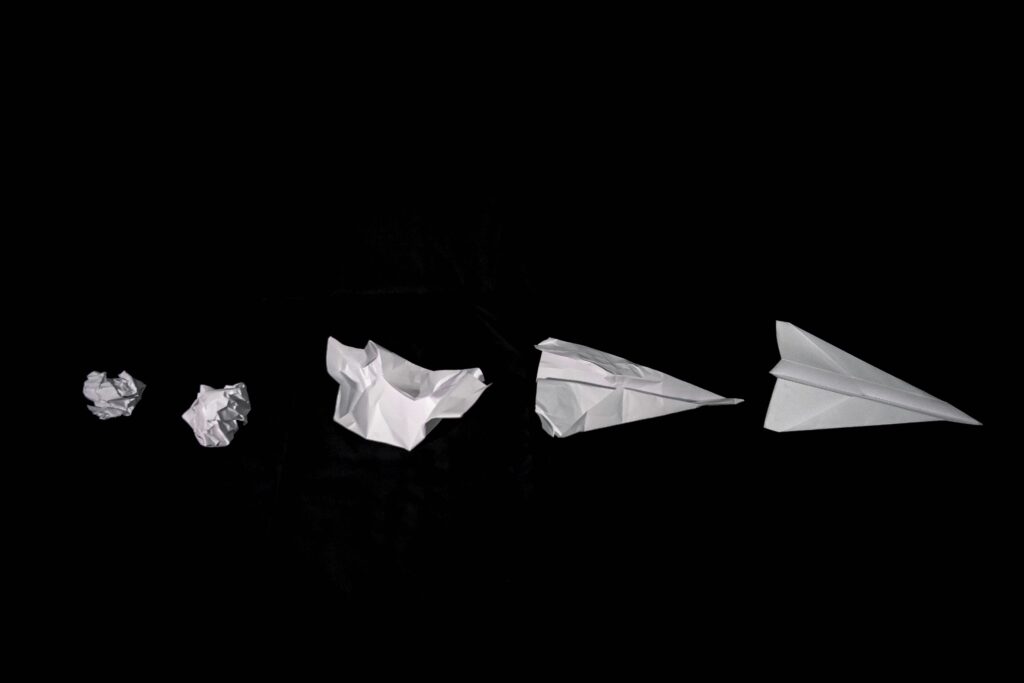

Rather than thinking of these theories as information, it’s much more useful to think about them as cultural artefacts, or as activities.

Some conspiracy theories are like live-action role-play games, where the action unfolds in real-time, and followers have a bearing on the way it plays out. At some level they’re also like wrestling: ‘the presentation of staged events as real, with the understanding that the audience is in on it … the eager suspension, on all sides, of disbelief.’

Perhaps the most useful way to think about conspiracy theories is to simply think about them as stories. They are tales that tell us something about real-life power and real-life pain.

The psychiatrist Carl Jung said that stories (specifically myths) reveal our collective unconscious. They tell us something about a society – its hopes, its fears. So …

What do conspiracy theories tell us about society?

Like myths, each conspiracy theory deals in its own constellation of symbolism and significance – and many are interconnected. But it’s clear there are some uniting themes: they captivate their audiences because they speak to their feelings and experiences.

They get told and retold because they resonate.

Why?

People are scared – they want clarity amid chaos

Conspiracy theories offer tidy explanations for the messy, complex world around us – that ‘this explains everything!’ dopamine hit. It’s like reading a really good definition of a complex idea: the feeling of a difficult thing made easier to hold.

Though theories themselves can be scary – like the secret and all-powerful paedophile rings or human sacrifice – in conspiracy-world your enemy tangibly exists, evil has a locus and can therefore be taken down. Chaos, confusion, alienation, loneliness, fear itself? These can’t be so easily defeated.

People want control – they do not trust the systems that exercise control over their lives

5G! Modern medicine! K-Pop! The world requires that we give trust to so many things most of us don’t really understand. These things become symbols for confusion, sometimes helplessness (kidding on the K-Pop thing).

Take 5G. It symbolises globalisation and technology, both emergent, rampant forces that have taken over our lives, communities, jobs, our way of life. That’s why I think people link it in their minds to COVID-19. The angst transmutes into a strange form, but the message is there: hold on, we didn’t ask for this!

People want to feel that they belong

Likely you’ve heard fear and control mentioned in the same sentence as conspiracy theories, but perhaps more powerful than either of these two combined is the sense of community that builds up around the theories.

From the personalised car number plates of Flat Earthers to the codewords and acronyms of QAnon, conspiracy theories make their followers feel not just welcome, but special, one of the select few. They meet other like-minded people. They see themselves and their experiences reflected in the words and explanations of others. They belong. Which is to say, outside these communities, they don’t feel they do.

This is clearly a highly complex, slippery issue that needs to be tackled at multiple levels. Looking into the world of conspiracy theories and, more broadly, mis/disinformation, it’s tempting to fling your hands up and give up in despair. ‘There’s no way we can bring people back from this!’

But we can’t afford to react that way. Continuing to speak within our own echo chambers just drives a deeper wedge, keeps us occupying different realities.

What can conspiracy theories teach policy experts about how to communicate?

Recognise that facts and evidence alone aren’t enough

The battle policy experts face is not just that when you proclaim facts that do not fit with people’s lived experience, they may not believe you. Rather, they may actually take the fact and use it to bolster their existing view of the world – the very one you’re trying to change.

For example, take a stat like in the UK ‘black and brown people account for half of all young people in jail’. Your audience might hear what you want them to hear: ‘racism means people of colour are over-policed and over-sentenced, more likely to face systemic obstacles to education and employment thereby increasing their likelihood of going to jail’. Or they might just hear: ‘people of colour are criminals’.

Here is where we return to stories. In story terms, facts are just the plot: what happens. If you’ve ever been too scared to watch a horror movie and instead just read the Wikipedia synopsis (just me?) you’ll know that simply having the major events described all matter-of-fact doesn’t really drive home the meaning and significance of events.

In other words, it’s not just about the events that happen but the way in which the story is told that matters.

Plot = what happened

Story = why what happened matters, what it means

The task for policy experts is to talk in a way that will resonate with people’s existing beliefs – no easy task.

Use stories for what they’re best at: communicating complexity

The irony of conspiracy theories is that, in many cases, they are stories used to oversimplify. That is a complete waste of storytelling potential.

Storytelling is not by nature reductive. It is the best tool we have for relaying the nuances and intricacies of our experiences, for entertaining multiple opposing realities at the same time.

For that reason, the result should never be to patronise, to treat with kid gloves, to offer simple solutions where none exist. Use stories to tell the truth, which is, more often than not: ‘it’s complicated’.

Remember a story’s power is, in part, about who is telling it

Perhaps the most significant of all conspiracy theories is Flat Earth. It represents, in the most on-the-nose way, what conspiracy theories are all about. Flat Earthers do what other conspiracy theorists merely do figuratively: they contest the shape of our reality. They point to the gap between what they’re told and what they see with their own eyes.

So much of this comes down to trust in the establishment. Flat Earth is a symbol of ‘if they’re lying to you about this, what else are they lying to you about?’ ‘They’ being ‘the people in charge’ – from the public-school system to the people holding office.

Lack of trust in the establishment – of which policy experts are clearly part – is a big driver of scepticism in emerging and established narratives.

If something you hear (a) doesn’t correspond to your lived experience and (b) comes from a person or organisation you don’t trust, then what reason do you have to listen?

Policy experts, think tanks in particular, have a long way to go if they are to be seen to represent a broader experience of our shared reality.

Don’t be afraid to entertain

Some conspiracy theories run like a Hollywood movie. Princess Diana’s death wasn’t an accident, she was murdered by MI6 at the request of the Queen? Tell me more!

Some are so bad they’re good. They’re the equivalent of cult ‘bad movies’ like The Room, or the Evil Dead 3 – the fact that they’re a little unhinged is part of their appeal.

Policy experts shouldn’t be afraid to rival the entertainment factor of these stories.

Being in the business of credibility doesn’t mean you can’t have a good time spreading research-based insights around the world. In fact, it can help.

We’re not saying turn your research into a soap opera, but there’s power in making your research ‘clear and compelling’.

Let’s be honest, there are plenty others out there who aren’t afraid to do the same.

What to read/ watch/ listen

Photo:Wesley Tingey

Are you ready to listen? In no particular order I recommend:

- First Draft on why we’re vulnerable to conspiracy theories and why misinformation is so hard to correct

- Vice on the Conspiracy Theory Singularity illustrating how individual conspiracy theorists are converging into a larger group calling themselves ‘the truth community’.

- Julia Ebner’s Going Dark: The Secret Social Lives of Extremists

- The Atlantic’s Shadowland series

- Netflix’s Flat Earth documentary Behind the Curve

- RUSI’s event on StratComms in the post-truth world

- BBC on What we can learn from conspiracy theories

- BBC’s The Infinite Monkey Cage on conspiracy theories (though be prepared for unhelpful intellectual smuggery)

- BBC’s CrowdScience on Why conspiracy theories exist (and how to talk to believers)

- The Conversation on What conspiracy theories have in common with fiction

- Alice Thwaite’s Democratic truth: A guide for the perplexed

- FrameWorks Institute on using story to power your numbers